Period:Unknown Production date:8thC-9thC

Materials:plaster, 石膏 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:monk/nun landscape 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) reading/writing

Dimensions:Height: 69 centimetres Width: 37 centimetres

Description:

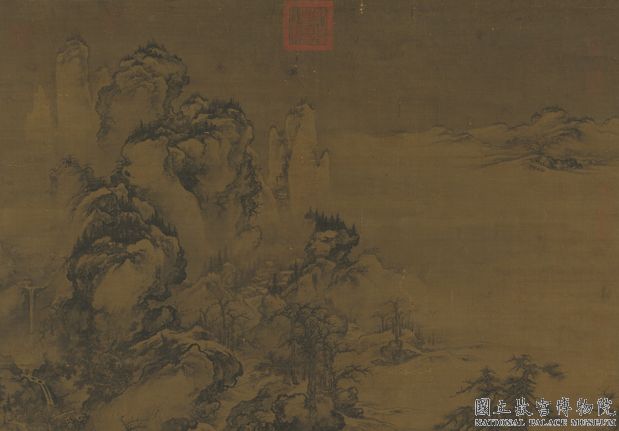

Fragment of wall-painting showing three monks seated inside a cave within a hill, writing on a tablet. Painted in ink and colours on plaster.

IMG

![图片[1]-wall-painting; 壁畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.279.g-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Paintings/mid_00010241_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-wall-painting; 壁畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.279.g-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Paintings/mid_00010241_002.jpg)

Comments:This piece belong to a group of 11 fragments (1919,0101,0.279.a-m) recovered by Stein from the lower part of the eastern walls of a shrine chamber. EnglishFrom Whitfield 1985:The site at Shorchuk, to which Stein gave the local name, Ming-oi (“Thousand Dwellings”), lies on a ridge to the north of the village, some sixty kilometers south of Karashahr. In antiquity all of the many shrines, with the exception of a series of caves, had been destroyed by fire, and had largely collapsed inwards. The fire, as well as being destructive, had a preservative effect upon parts of the stucco ornament of the shrines, especially in the case of the heads of many figures, which had been made with greater care and attention than the limbs and bodies. By and large, wall paintings did not survive, with the exception of fragments from one shrine. Apart from small fragments, the pieces shown here and in the following plates are the only items of wall painting from the Stein Collection now in the British Museum; the rest are all in New Delhi. The fragments come from a temple in the northwestern part of the site, the only recognizable part of a complex of halls and rooms. When examined by Stein, he thought that the entrance hall had in fact already been partially cleared. However, although Grunwedel had earlier visited the site in Jone 1906 (Grunwedel, 1912, p. 191ff), Oldenburg was later to recover more paintings from this same entrance hall (see below). Beyond the entrance hall was a cella five metres square, the entrance of which had once been flanked by a statue on each side. The cella itself was filled with burnt brickwork; on its east and west sides vaulted passages led to a narrow chamber, also vaulted, behind the cella. It was in this narrow vaulted chamber, designated xiii by Stein, that the paintings shown here were found. They formed a continuous dado along the foot of the outer wall for about three and a half metres in the eastern half of the chamber. Stein also recovered one panel (Mi. xiii. 10) from the western passage, which had been blocked by debris before the fire. This panel is also in the British Museum, but the surface has deteriorated since it was reproduced in Serindia (Pl. CXXIV). The series of panels begins with scenes of monks receiving instruction. The senior monks, some of them clearly aged (Pl. 95-2), are seated on square stools, some with closed-in sides, others open showing the legs and stretchers, and incorporating a foot-rest. Their pupils, on the other hand, kneel in front of them. In the first scene (Pl. 95-1), both master and pupils are writing on tablets, which have the long narrow shape of pothi leaves. In the sky above, a descending apsaras brings a writing brush, in an interesting variation on the more usual theme of scattering flowers (Pl. 95-2). In another scene, the figure descending on clouds from above appears from his dress to be a Buddha; below him two groups of monks and devatas kneel in adoration (Pl. 95-4). Another scene, only partially preserved, shows a monk prostrating himself in front of his master, in a gesture reminiscent of the Vow before Dipankara (Pl. 95-8; cf. Pl. 117). Despite the colourfulness of this series of panels, they are easily outshone by the two larger panels recovered from the same shrine by Oldenburg, which are now displayed in the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. They are reproduced in colour in his report (Oldenburg, 1914, Pls. IX, X). One of them shows a lady of high rank, apparently in great grief, as she raises her hand to her face. Nearby kneels a small boy in typical Uighur costume. They are both just behind a very much larger figure of the Buddha. The other panel, which must have been on the other side of the doorway in the main hall of the shrine, shows two Bodhisattvas and a number of monks, some of them kneeling. Both paintings are very finely drawn and lavishly coloured, and gold is used quite extensively. By comparison, the Stein panels, occupying a relatively humble and obscure position low on the rear wall of the rear chamber of the shrine, are correspondingly muted in both colouring and subject matter. They are, however, extremely important since the landscape settings still preserve elements that must derive from the art of the Kizil caves. Each of the monks seated and transcribing texts is placed in a niche or cave within a hill whose contours rise in a series of rounded steps, outlined in ink (Pls. 95-10, 11). The hills are lined up one beside the other, and a second row is seen above them. It is principally the stepped contour of the hills that recalls the ceilings of many of the Kizil caves, where jataka stories are illustrated in a landscape setting of stylized hills, repeated over the whole roof vault. Although the arrangement in the Ming-oi panels is not continuous so as to fill the whole space, there are other similarities as well, namely the occasional tree or animal seen around the edges or the hills (Pl. 95-11). Thus while the costume and hair fashion of the small kneeling boy (Pl. 95-6) is clear evidence of the Uighur dating of these paintings, at the latest they are eighth or ninth century. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1985:斯坦因採用當地語言“明屋(千家)”命名的此遺址,在焉耆向南約60公里處,散佈在碩爾楚克北面的山地裏。除石窟外,許多寺院在古代都曾遭受過火災,向里倒塌。當然,火災有帶來破壞的一面,但也有有利的一面,寺院用灰泥裝飾部分,特別是佛像頭部,它比軀體、手腳製作的更認真,燃燒使之變得更結實,起到了保護的效果。除了一個寺院的一個壁畫殘片外,壁畫幾乎都沒有留下。另外,斯坦因收集的壁畫,藏在大英博物館的,除了極小的斷片外,大概只有本圖所展示的作品了,其它都收藏在新德里。本圖的壁畫是在位于遺迹西北部只剩大廳和幾閒屋的佛寺中發現的。斯坦因認爲,在自己開始考察之前,入口的大廳曾有人涉足。而格倫威德爾訪問此地是1906年6月(參照Grunwedel:Alt-Buddhistische Kultstutten in Chinesische-Turkistan 1912,191頁),後奧登堡從此入口的大廳發現了另一壁畫(見下)。入口的大廳深處有5米見方的正方形内殿,其門兩側似乎有過塑像。佛堂本身被燒塌的瓦礫埋沒,其東西兩端是帶拱形天井的側廊,通向同樣有拱形天井的佛堂背後狹小的內室。本圖展示的壁畫是,從斯坦因命名爲xiii的此有拱形天井的狹小內室發現的。壁畫是內室外壁東側一半約3.5米長的牆圍子。斯坦因還從火災之前就被堆積層堵塞的西邊側廊發現了一面壁畫(Mi.xiii.10)。那壁畫也收藏于大英博物館,其畫面狀態比當時《西域》(參照圖CXXI V)中展示時的還要惡化。壁畫首先從多個比丘聽授教法的場景開始。年長的比丘腰倚方形的凳子,能明顯能看出年齡(第95-2圖)等,有的腳被斜向橫過的裝飾遮隱,而大多數連放腳或腿的臺子都被描繪出來。另一面,弟子們在前面屈膝而坐。第一場景(第95-3圖)中,無論師父還是弟子都在細長的菩提葉上寫字。上空繪著散花的飛天手持毛筆(圖95-2)。而在另一場景中,從上空乘雲飛來的像是偏袒右肩的佛,其下有兩組比丘和天部在合掌贊頌(圖95-4)。另一場景只保存了一部分,可辨出師父前匍匐的虔誠比丘的身姿(圖95-5)。此景象,使人想起布髮本生的場面(參照圖117)。此連環壁畫儘管色彩豐富,但遠不及奧登堡從同一佛寺發現現存于艾爾米塔什美術館的兩幅大壁畫。在其報告中刊載了那兩幅壁畫的彩色圖版(參照Oldenburg,Russkays Turkestanskaya Ekspedit-siya.Goda,1909~1910,1914,圖版IX,X)。其中一面上,有手貼在臉,沈浸於深深地悲哀中的貴族女性,旁邊跪著穿典型回鶻裝的少年,兩人的背後立著極大的佛像。另一面壁畫無疑與主室門口的其它壁畫不同,那裏描繪的是兩身菩薩和數身比丘,有幾個比丘是跪姿。兩面都是精致的描繪,使用了華麗的色彩,還加了大量的金彩。相比之下,斯坦因的壁畫也許是描繪在內室內壁下部這一既不重要也不顯眼的場所,色彩和主題都稍差。但在此壁畫可以看出克孜爾石窟壁畫風格的山水描繪,這一點很重要。比丘各自坐在山中的石窟或佛龕中抄寫經文。山的輪廓用墨繪成圓頭的臺階狀(圖 95-10, 11)。那山排成一列,其上方可見第二列。臺階狀的山的輪廓使人想起克孜爾石窟的多數天井畫。克孜爾石窟裏,半球形的整面天井上,描繪著以模式化的山水爲背景的本生圖。明屋壁畫上的山水雖然不是連续遮掩整面,但還能見到其他類似點,就是那些山上隨處可見的樹和動物等(圖95-11)的描繪。跪拜的少年(圖95-8)的衣服和髮型也能够證明此連環的壁畫是回鶻時期的,其年代最遲不過8~9世紀。

Materials:plaster, 石膏 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:monk/nun landscape 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) reading/writing

Dimensions:Height: 69 centimetres Width: 37 centimetres

Description:

Fragment of wall-painting showing three monks seated inside a cave within a hill, writing on a tablet. Painted in ink and colours on plaster.

IMG

![图片[1]-wall-painting; 壁畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.279.g-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Paintings/mid_00010241_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-wall-painting; 壁畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.279.g-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Paintings/mid_00010241_002.jpg)

Comments:This piece belong to a group of 11 fragments (1919,0101,0.279.a-m) recovered by Stein from the lower part of the eastern walls of a shrine chamber. EnglishFrom Whitfield 1985:The site at Shorchuk, to which Stein gave the local name, Ming-oi (“Thousand Dwellings”), lies on a ridge to the north of the village, some sixty kilometers south of Karashahr. In antiquity all of the many shrines, with the exception of a series of caves, had been destroyed by fire, and had largely collapsed inwards. The fire, as well as being destructive, had a preservative effect upon parts of the stucco ornament of the shrines, especially in the case of the heads of many figures, which had been made with greater care and attention than the limbs and bodies. By and large, wall paintings did not survive, with the exception of fragments from one shrine. Apart from small fragments, the pieces shown here and in the following plates are the only items of wall painting from the Stein Collection now in the British Museum; the rest are all in New Delhi. The fragments come from a temple in the northwestern part of the site, the only recognizable part of a complex of halls and rooms. When examined by Stein, he thought that the entrance hall had in fact already been partially cleared. However, although Grunwedel had earlier visited the site in Jone 1906 (Grunwedel, 1912, p. 191ff), Oldenburg was later to recover more paintings from this same entrance hall (see below). Beyond the entrance hall was a cella five metres square, the entrance of which had once been flanked by a statue on each side. The cella itself was filled with burnt brickwork; on its east and west sides vaulted passages led to a narrow chamber, also vaulted, behind the cella. It was in this narrow vaulted chamber, designated xiii by Stein, that the paintings shown here were found. They formed a continuous dado along the foot of the outer wall for about three and a half metres in the eastern half of the chamber. Stein also recovered one panel (Mi. xiii. 10) from the western passage, which had been blocked by debris before the fire. This panel is also in the British Museum, but the surface has deteriorated since it was reproduced in Serindia (Pl. CXXIV). The series of panels begins with scenes of monks receiving instruction. The senior monks, some of them clearly aged (Pl. 95-2), are seated on square stools, some with closed-in sides, others open showing the legs and stretchers, and incorporating a foot-rest. Their pupils, on the other hand, kneel in front of them. In the first scene (Pl. 95-1), both master and pupils are writing on tablets, which have the long narrow shape of pothi leaves. In the sky above, a descending apsaras brings a writing brush, in an interesting variation on the more usual theme of scattering flowers (Pl. 95-2). In another scene, the figure descending on clouds from above appears from his dress to be a Buddha; below him two groups of monks and devatas kneel in adoration (Pl. 95-4). Another scene, only partially preserved, shows a monk prostrating himself in front of his master, in a gesture reminiscent of the Vow before Dipankara (Pl. 95-8; cf. Pl. 117). Despite the colourfulness of this series of panels, they are easily outshone by the two larger panels recovered from the same shrine by Oldenburg, which are now displayed in the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. They are reproduced in colour in his report (Oldenburg, 1914, Pls. IX, X). One of them shows a lady of high rank, apparently in great grief, as she raises her hand to her face. Nearby kneels a small boy in typical Uighur costume. They are both just behind a very much larger figure of the Buddha. The other panel, which must have been on the other side of the doorway in the main hall of the shrine, shows two Bodhisattvas and a number of monks, some of them kneeling. Both paintings are very finely drawn and lavishly coloured, and gold is used quite extensively. By comparison, the Stein panels, occupying a relatively humble and obscure position low on the rear wall of the rear chamber of the shrine, are correspondingly muted in both colouring and subject matter. They are, however, extremely important since the landscape settings still preserve elements that must derive from the art of the Kizil caves. Each of the monks seated and transcribing texts is placed in a niche or cave within a hill whose contours rise in a series of rounded steps, outlined in ink (Pls. 95-10, 11). The hills are lined up one beside the other, and a second row is seen above them. It is principally the stepped contour of the hills that recalls the ceilings of many of the Kizil caves, where jataka stories are illustrated in a landscape setting of stylized hills, repeated over the whole roof vault. Although the arrangement in the Ming-oi panels is not continuous so as to fill the whole space, there are other similarities as well, namely the occasional tree or animal seen around the edges or the hills (Pl. 95-11). Thus while the costume and hair fashion of the small kneeling boy (Pl. 95-6) is clear evidence of the Uighur dating of these paintings, at the latest they are eighth or ninth century. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1985:斯坦因採用當地語言“明屋(千家)”命名的此遺址,在焉耆向南約60公里處,散佈在碩爾楚克北面的山地裏。除石窟外,許多寺院在古代都曾遭受過火災,向里倒塌。當然,火災有帶來破壞的一面,但也有有利的一面,寺院用灰泥裝飾部分,特別是佛像頭部,它比軀體、手腳製作的更認真,燃燒使之變得更結實,起到了保護的效果。除了一個寺院的一個壁畫殘片外,壁畫幾乎都沒有留下。另外,斯坦因收集的壁畫,藏在大英博物館的,除了極小的斷片外,大概只有本圖所展示的作品了,其它都收藏在新德里。本圖的壁畫是在位于遺迹西北部只剩大廳和幾閒屋的佛寺中發現的。斯坦因認爲,在自己開始考察之前,入口的大廳曾有人涉足。而格倫威德爾訪問此地是1906年6月(參照Grunwedel:Alt-Buddhistische Kultstutten in Chinesische-Turkistan 1912,191頁),後奧登堡從此入口的大廳發現了另一壁畫(見下)。入口的大廳深處有5米見方的正方形内殿,其門兩側似乎有過塑像。佛堂本身被燒塌的瓦礫埋沒,其東西兩端是帶拱形天井的側廊,通向同樣有拱形天井的佛堂背後狹小的內室。本圖展示的壁畫是,從斯坦因命名爲xiii的此有拱形天井的狹小內室發現的。壁畫是內室外壁東側一半約3.5米長的牆圍子。斯坦因還從火災之前就被堆積層堵塞的西邊側廊發現了一面壁畫(Mi.xiii.10)。那壁畫也收藏于大英博物館,其畫面狀態比當時《西域》(參照圖CXXI V)中展示時的還要惡化。壁畫首先從多個比丘聽授教法的場景開始。年長的比丘腰倚方形的凳子,能明顯能看出年齡(第95-2圖)等,有的腳被斜向橫過的裝飾遮隱,而大多數連放腳或腿的臺子都被描繪出來。另一面,弟子們在前面屈膝而坐。第一場景(第95-3圖)中,無論師父還是弟子都在細長的菩提葉上寫字。上空繪著散花的飛天手持毛筆(圖95-2)。而在另一場景中,從上空乘雲飛來的像是偏袒右肩的佛,其下有兩組比丘和天部在合掌贊頌(圖95-4)。另一場景只保存了一部分,可辨出師父前匍匐的虔誠比丘的身姿(圖95-5)。此景象,使人想起布髮本生的場面(參照圖117)。此連環壁畫儘管色彩豐富,但遠不及奧登堡從同一佛寺發現現存于艾爾米塔什美術館的兩幅大壁畫。在其報告中刊載了那兩幅壁畫的彩色圖版(參照Oldenburg,Russkays Turkestanskaya Ekspedit-siya.Goda,1909~1910,1914,圖版IX,X)。其中一面上,有手貼在臉,沈浸於深深地悲哀中的貴族女性,旁邊跪著穿典型回鶻裝的少年,兩人的背後立著極大的佛像。另一面壁畫無疑與主室門口的其它壁畫不同,那裏描繪的是兩身菩薩和數身比丘,有幾個比丘是跪姿。兩面都是精致的描繪,使用了華麗的色彩,還加了大量的金彩。相比之下,斯坦因的壁畫也許是描繪在內室內壁下部這一既不重要也不顯眼的場所,色彩和主題都稍差。但在此壁畫可以看出克孜爾石窟壁畫風格的山水描繪,這一點很重要。比丘各自坐在山中的石窟或佛龕中抄寫經文。山的輪廓用墨繪成圓頭的臺階狀(圖 95-10, 11)。那山排成一列,其上方可見第二列。臺階狀的山的輪廓使人想起克孜爾石窟的多數天井畫。克孜爾石窟裏,半球形的整面天井上,描繪著以模式化的山水爲背景的本生圖。明屋壁畫上的山水雖然不是連续遮掩整面,但還能見到其他類似點,就是那些山上隨處可見的樹和動物等(圖95-11)的描繪。跪拜的少年(圖95-8)的衣服和髮型也能够證明此連環的壁畫是回鶻時期的,其年代最遲不過8~9世紀。

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)