Period:Tang dynasty Production date:8thC(late) (circa)

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise monk/nun architecture 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 建築 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 177.60 centimetres Width: 121 centimetres

Description:

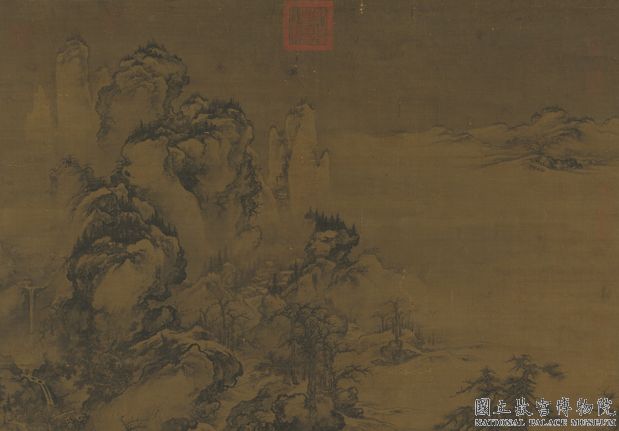

Painting of the Paradise of Śākyamuni, shown with his retinue of bodhisattvas and monk disciples in an architectural setting, and with newly-born infant souls seated on lotuses. Side scenes illustrate the story of Prince Sujati’s filial devotion, with inscriptions in cartouches from the Sutra on Requiting Kindness (Baoen jing). Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000312_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000387_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00309671_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00322172_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Whole_ii.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_1.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_2.jpg)

![图片[9]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_3.jpg)

![图片[10]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_4.jpg)

![图片[11]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_5.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:This painting demonstrates the way in which sutras were illustrated in the art of Dunhuang, both in the wall paintings and in those on silk, as it can be described as a bianxiang 變相,or illustration to the Dafangbianfo baoen jing 大方便佛報恩經.The concept of baoen, or the requiting of blessings received, is one that must have easily become popular in China, since it accorded well with Chinese traditional values of filial piety. In fact the story of Prince Sujāti is taken from the xiaoyang 孝養,or filial devotion section of the Baoen-sūtra. The subject is the duty owed by a child to his parents in requitement of the blessings received from them. The merit earned by such requitement could be much greater than the original blessings (Mochizuki, 1973-74,p.4551).In the present painting, the side scenes on the right side show Sujāti’s filial devotion, to the extent of sacrificing his own body to feed his parents in a time of crisis. At the same time, the splendours and delights of the Pure Land of Sākyamuni are shown in the centre.The painting is virtually complete, including a painted valance and the plain sewn-on silk border, except for part of the centre foreground. Its rich, yet delicate colouring, though faded, is in places extraordinarily well preserved and shows the full splendour of Buddhist painting in the High Tang period. Despite this great beauty of colour and form, the painting has rarely been reproduced before (Matsumoto, 1937, Pl. 58; Stein, Thousand Buddhas, Pl. VI, part only), and then only in monochrome. It is a fine example of a more developed paradise scene than Buddha Preaching the Law (Pl.7). In order to help the faithful to visualize the splendours of the Pure Land into which they could hope to be reborn, the depiction includes a growing retinue of attendants about the Buddha and a magnificent setting, with musicians below and pavilions above, representing the delights and beauties of the Pure Land. The main part of the assembly is gathered on a platform rising out of a lotus lake: here infant souls, newly reborn, are seen on lotus flowers joining in adoration (Pl.8-8). To either side of this assembly are narrow side scenes set in landscapes. These represent episodes from three of the nine parts of the Baoen-sūtra. Each scene is identified by a cartouche inscribed with the relevant part of the story, so that the painting could easily be used for the instruction of the faithful.On the right side, from the top downwards, are seven episodes from the story of Prince Sujāti (Fig.22). The top scene, showing an official in red bowing before a king, is accompanied by a caption introducing the king of Vārānasī and his minister Rahula, who had conceived traitorous ambitions against him. In the second scene “a spirit appears out of space and warns the prince” of the impending attack by Rahula’s troops. Subsequent scenes show the flight of the king, his wife and son by a ladder from the walls of the city and their journey, taking with them a bag of provisions. In the sixth scene, when these have been exhausted, Sujāti is seen interposing between the king, with upraised sword, and the queen, whom he is about to kill. At the bottom, Sujāti, his body covered in wounds, is left crawling by the roadside as the king and his wife continue on their way. For the remainder of the story, see the side scenes to Stein painting 1(Figs.34, 35). The left side is divided between two stories: from the top downwards five cartouches describe part of the story of the deer mother, in which a deer conceives after drinking water in which a rishi had washed his clothes (Fig.21). Her child is shown as a woman, twice seen walking around the rishi’s cave, with lotuses springing from her footprints (Pl.8-7). From the bottom, another three scenes give part of the story of the Good and Wicked Sons, also from the Baoen-sūtra. At the bottom is the king of Vārānasī with one of his wives. The middle scene shows the childless king in front of a shrine performing ceremonies of supplication, as a result of which two sons were eventually born and named after the characters of the king’s first and second wives. The third scene, above this, shows the fulfilment of the Good Son’s vow to fill the land with treasures. The inscriptions supply more detail than the painter was able to show in these scenes, and in particular the lowest caption refers to the Good Son’s fast and to his mother’s intercession with the king to allow him to enter the ocean and cull its treasures in fulfillment of his vow.All of these scenes are set in landscape, with a few simple conventions to aid in the telling of the story. Thus the capital of the country of Vārānasī is represented by a city wall running across the narrow picture space, and a single pavilion, open at the front and with a flight of steps, serves both as the shrine where the king makes his vows (Fig.21, upper right)and as the setting, perhaps the palace, where a spirit appears to warn the king of his minister’s impending treachery(Fig.22,upper right).The other scenes are all appropriately set in landscapes which, by means of triangular slopes, zig-zag banks and flat spaces between, offer spaces for the incidents of the story. Some of the slopes, for example in the detail shown from the story of the deer (Pl.8-7), feature tall peaks and numerous plants and trees. The pointed forms of these peaks find counterparts both in the wall paintings and in some of the banners showing scenes from the life of the historical Buddha (Pl.39-1). Broad ink strokes are used to give further emphasis to the curved slopes and the vertical banks.In this painting the donors too are represented at the foot of these side scenes: on the right a nun and a novice, and on the left a woman, named as the lady Meng, kneeling and holding an incense burner. Her modest attitude, demure headdress and high-waisted robe all suggest a date still in the eighth century A.D.The architecture of the buildings above the paradise assembly reflects the appearance of Tang dynasty Buddhist temples, with a gatehouse and main hall on the central axis, connected by galleries to two-storeyed pavilions on either side of the main courtyard (Pl.8-3). The gateway itself is largely hidden by the Bodhi trees and canopy over the Buddha, but its great hipped roof, with the eaves seen from below and large “owl’s tail” finials, stretches across half the picture as a kind of canopy for the whole assembly. Beyond it, a raised and balustraded causeway leads to the main hall. This has just three bays. Simple brackets crown the columns, and straight struts provide additional support between them. The space within the hall revealed by the rolled-up bamboo screens is occupied by a low dais, beyond which is a painted screen.Although the central hall is quite small, its relationship with the gateway gives it a good deal of prominence. Both are seen from below so that it almost appears with the latter as a tall, two-storeyed building, a much larger version of the two-storeyed side pavilions. The latter display the same sequence of dark lower roof, balcony and upper roof with dark ridges and acroteria, but they are seen from above. On either side of the main axis, the open galleries have white-painted walls with square wooden windows and doors open to an interior beyond; there are lotus pedestals, six in all, along the galleries, but no figures on them. Above the roofs, the Buddhas of the Four Directions rise on cloud supports. Finally, the platform from which the entire complex rises is lined with panels of tilework elaborately decorated with floral patterns.The painting is endowed throughout with an extraordinary richness of colour in which dark and light are used to their best effect. Examples of the way in which the painter has achieved this can be seen in the main group of deities in the centre of the painting. Here, a black ground is used behind the figures, admirably setting off the rainbow hues of the haloes. Higher up, the black roofs of the gateway and side pavilions have a similar role. The haloes themselves are carefully orchestrated: among the lesser figures, the majority have plain colours (five blue, four green). They accord well with the prevailing tones in the whole painting. On them the petals (oblong or broad overlapping, respectively) are traced in fine white lines, now barely visible. The others (four with white cloud scrolls on a purple ground, and four with similar scrolls on orange and red) are evenly distributed to encircle the main figure. Only four are fully visible, while the others are partially obscured by the haloes of the three main figures. These in turn are far more elaborate. It is not necessary to describe them, as they are clear in the plates, but it may be observed that only that of the Buddha is adorned with a series of triangles appearing between the outer rows of petals. These triangles just touch to form a regular dentellation; in later paintings they are separated so as to appear more like barbed points, and their use gradually spreads from the main Buddha to the Bodhisattvas and eventually to lesser figures as well.The figures of the two Bodhisattvas, their compassionate faces seen from the front but gently inclined towards the central Buddha, invite comparison with wall paintings of the early Tang, such as in Cave 322(Dunhuang bihua, Pls.124-25). They retain a compactness of design although the richness of their adornments clearly indicates a somewhat later date for the painting on silk. In the foreground, the single dancing figure (Fig.20), poised between two garudas, sways and holds aloft long narrow scarves, striped in green and brilliant purple; these, too, are reminiscent of earlier wall paintings, e.g., Cave 220 (ibid., Pl.115).Bright colours such as purple and red are used in the garments of the minor Bodhisattvas and musicians, symmetrically disposed in the groups on either side.The silk of which the painting is made up consists of one full width of 55.5cm,and two half widths of about 27 cm each. The resulting painted area is thus slightly wider than that of Pl.7, and of course much longer, but the main figures are very much smaller, principally as a result of accommodating the narrative scenes on either side. By the careful manipulation of scale, however, the artist has been able to avoid any feeling of crowding.Finally, a feature which deserves special mention is the elegantly finished painted valance (Pl.8-2) and borders of flowers. The valance is elaborately made up with two double white streamers tied in symmetrical bows and dividing it into thirds. An actual example of such a valance, similarly divided by prominent streamers, is preserved in the Stein collection (Vol.3, Pl.8). Above the valance is a wide border of pairs of red florets edged in yellow with green and yellow leaf motifs. Similar but narrower borders with single florets separate the main paradise scene from the narrative side scenes. The present painted valance and the painted floral border above it are on a single separate piece of silk sewn onto the top edge of the painting. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1982:敦煌藝術中用壁畫或絹畫來表現佛經內容的繪畫,叫“變相”。此圖正是這種變相,即大方便佛報恩經變相。“報恩”的概念,正與中國傳統道德觀念中的“孝” 相符合,因此在中國很容易普及。事實上須闍提太子的故事即源自《報恩經•孝養品》,主旨講回報父母的恩德是子孫應盡的義務,回報父母的要比從父母那裏得到的多,是報恩中的美德(望月信亨《佛教大辭典》,1973-74,4551頁)。此作品右側邊緣表現的是須闍提太子的孝道故事,面對危機,將自己身體提供給父母解救饑餓。與此同時,中央則是描繪充滿光明歡樂的釋迦牟尼淨土。此畫相對完整,依然保留著畫著的帷幕及四周縫製的素色絹邊,只有前景中間部分稍有損壞。雖然褪了色,但某些部分仍然保留了豐富濃重的色彩,顯示了盛唐時期佛教繪畫的壯美。盡管此畫顔色、形態都非常美,但至今爲止,卻很少有將其製成圖版介紹的(松本榮一《敦煌畫研究》,1937,圖58,斯坦因《千佛洞》,圖6,僅是局部),並且也只是單色圖版。這是比上圖(圖7)《樹下說法圖》有更大發展的淨土圖的絕好的例子。為幫助信徒能夠看到希望往生的淨土的壯麗,本圖描述了佛和周圍衆多的眷屬,下端的歌伎、上端的樓閣,構成了壯觀的場面,用以描繪淨土的歡樂與華麗。聖衆的大半集中于蓮池中的寶臺上,代表再生靈魂的化生童子坐在蓮花上合掌禮拜,(圖8-8)。在聖衆兩側狹窄的邊緣,描繪有山水爲背景的故事圖,《報恩經》所記載的九段故事,有三段被描繪於此。各場景內容可以據長方形榜題來確認,這樣這幅畫可以很容易地實現對信徒的教化。右側邊緣,從上到下繪有七段須闍提太子的故事(參見Fig.22)。最上段描繪的是身著紅衣的大臣參拜大王,附有“波羅奈國大王和心生惡逆的大臣羅睺” 的標題。第二段是警告羅睺欲派兵馬襲擊的“虛空神祗的飛來”場面。與此相接的是大王、夫人和太子在城牆上架梯逃亡,以及攜帶食糧長途跋涉的場面。第六段是,食糧斷盡,大王舉起劍欲殺妃子時,須闍提太子橫插其間的場面。最下段描繪的是,受傷的須闍提太子留在道旁緩慢地爬行,大王和夫人則繼續旅程的場面。有關故事的剩餘部分,可以參看斯坦因繪畫1(參看Figs.34,35)。左側邊緣(參照單色圖版第21圖)分爲兩段故事,上方五段榜題記述《鹿母本生》的一部分,是鹿飲了仙人洗衣服的水而妊娠的故事(參看Fig.21)。鹿所産下的孩子長成婦人,用了兩個場面來描繪當她繞行仙人所住洞窟時,足下盛開了蓮花(參看圖8-7)。最下段表現的是《報恩經》中的善友太子、惡友太子故事的三個場面。下段中繪有波羅奈國王和他一位夫人,中間描繪沒有子嗣的大王在神殿前做祈願儀式,結果國王得到二個孩子,針對他們各自不同的性格,將第一夫人的孩子名爲善友,第二夫人的孩子名爲惡友。第三段是善友太子將財寶填滿國庫的誓願得到了實現的場面。長方形榜題上詳細記述著繪畫中未表示的內容,特別是最下段的榜題,記述著善友太子絕食、母后爲了使太子實現得到摩尼寶珠的誓願,勸解大王同意他赴大海。所有這些場面是在山水畫間展開的,爲了使場面更易理解,多加有極其簡單的象徵性的事物。諸如把波羅奈國的國都描繪爲橫穿狹窄畫面的城壁,國王施願的神殿(參看Fig.21,右上角)、神祗警告大臣即將叛逆而出現的場所(參看Fig.22,右上角),大概是宮殿,統統用正面入口和一段臺階來表示。山水畫的其它場景設計也非常恰當,三角形山丘與“Z”字形岸邊之間的空間,用來安排故事情節。一些山丘,如《鹿母本生》的細部(參看圖8-7)中,山的尖頂、無數的草木都很引人注目。在壁畫和反映佛傳內容的幡畫(參看圖39-1)中均有不少極為類似的尖頂山。爲了強調山凹處和峭立的河岸等,採用了較粗的墨線。此幅繪畫中,供養人像繪在兩邊緣最下端。右邊有比丘和比丘尼,左邊是“孟”姓的婦人,跪持帶柄香爐。從婦女恭恭敬敬的神態以及文雅的髮髻、高胸的衣裳等看,該繪畫的年代仍是8世紀。淨土上方的建築物構造爲中軸線上的門和中堂、配于中庭兩端的二層樓等,都有回廊連接,體現出唐時期佛教寺院的外觀(參看圖8-3)。門前的大部分被佛上方的華蓋和菩提樹遮住,仰視狀態的軒和大鴟尾攏於屋脊的巨大屋頂,橫跨著畫面的大半部分,猶如是全體聖衆的華蓋一般。其上方描繪的是通向中堂具有勾欄的臺階。中堂有三間,柱頂有簡單的斗栱,中間可以望見表示進深的數根柱子。中堂前面的竹簾上卷,內部有須彌壇,其旁有繪畫的隔扇。中堂極小,但從與之相連的門上卻感覺不出。因爲門和中堂都被描繪成從下往上仰視的形態,與宛如擴大了的兩翼的二層樓,看似是一體的建築物。這是因爲兩翼樓閣的的配色,一層和門樓的屋頂採用了相同的黑色,二層的勾欄配合中堂的勾欄,二層的屋頂和中堂的屋頂相同,都配有同樣帶黑邊的鴟尾。但在構圖上,樓閣卻是表現爲從上向下俯瞰的狀態。中軸線左右兩邊連綿的回廊,內側無圍牆,外側牆壁塗成白色,處處顯現有向內打開的方形木窗和門。回廊中擺放著蓮花座,共六個,上面並無乘坐者。屋頂上方,有代表四個方向的四方佛乘坐在雲彩上。最后,寶壇平地而起,上面貼有一層層非常美麗的花磚。此繪畫巧妙地運用了顔色的濃淡對比變化,顯現出極其豐富的色彩,以達到最佳效果。仔細看畫面中央的一群聖像,便可窺見繪畫作者使用色彩的理念。諸尊背景採用黑色,使背光的繁多顔色更加顯眼奪目,上方的門樓和側樓屋頂所採用的黑色亦起著同樣作用。諸尊背光色彩也非常細心地考慮其相互之間的協調:小尊背光多爲單色(五例青色,四例綠色),整體畫面的色調和諧均勻。背光上用白線繪著絢麗的紋樣(橢圓形狀和寬幅的重瓣形狀),但由於已經脫落,現在幾乎無法辨認。其他小尊的背光(紫色底子上有白色卷雲紋樣的四例,橙色和赤色底子上有同樣卷雲紋樣的四例),等距離地環繞在主尊的周圍。其中,能看見全身的只有四尊,其他被主要的三尊背光遮住了一部分。三尊主尊的背光並不精致,圖版中可見背光明亮,無需詳細說明。值得注意的是如來背光外周連接著的三角形裝飾。三角形互相銜接,有規律地排列著。但隨著時代的後移,每一個三角形都獨立存在,形狀更尖,使用範圍也從如來依次擴大到菩薩和周圍的諸小尊。脅侍的二菩薩深懷慈悲地面向前方,但略微傾向中央的如來,對比第322窟(參照《敦煌壁畫》圖124、125)等初唐時期的壁畫,從裝飾的豐富,簡潔的圖樣看,壁畫的年代不可能比絹畫晚多少年。前景中,在二隻迦陵頻伽之間,一位舞伎在空中舞動著綠、紫兩色飄帶翩翩起舞(參見Fig.20),這讓人想起第220窟(參見《敦煌壁畫》圖115)等早期壁畫中畫面左右兩側對稱的諸像,小菩薩或樂伎穿著鮮豔的紫色和紅色服裝。此幅絹畫由一幅寬55.5cm的絹和兩幅寬約27cm的半幅絹構成。所以畫面比圖7稍寬,當然縱向更長。但兩邊插入了故事畫,主要部分的諸尊則變得略小。然而藝術家巧妙處理了比例關係,避免了擁擠的感覺。最後要特別指出的一點是,極具雅趣的繪製的垂幕和花柄紋樣帶(參見圖8-2)。細心描繪的垂幕,配有兩根左右對稱的白色蝴蝶結飄帶,將整體分成三段。這種垂幕在斯坦因收集品(參見第3卷圖8)中存有實物,和這個垂幕一樣,有飄帶裝飾,把整體分爲三段。垂幕的上面有很寬的紋樣帶,紋樣是每兩朵有黃色邊緣的紅色小花,與綠和黃色葉子的組合。中央淨土圖與兩側故事畫的界限則是只有一朵同樣雅致的小花的窄幅紋樣帶。上部的垂幕和紋樣帶是繪在縫於畫面上端的另一絹子上。

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise monk/nun architecture 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 建築 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 177.60 centimetres Width: 121 centimetres

Description:

Painting of the Paradise of Śākyamuni, shown with his retinue of bodhisattvas and monk disciples in an architectural setting, and with newly-born infant souls seated on lotuses. Side scenes illustrate the story of Prince Sujati’s filial devotion, with inscriptions in cartouches from the Sutra on Requiting Kindness (Baoen jing). Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000312_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000387_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00309671_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00322172_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Whole_ii.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_1.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_2.jpg)

![图片[9]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_3.jpg)

![图片[10]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_4.jpg)

![图片[11]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.12-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC612_Detail_5.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:This painting demonstrates the way in which sutras were illustrated in the art of Dunhuang, both in the wall paintings and in those on silk, as it can be described as a bianxiang 變相,or illustration to the Dafangbianfo baoen jing 大方便佛報恩經.The concept of baoen, or the requiting of blessings received, is one that must have easily become popular in China, since it accorded well with Chinese traditional values of filial piety. In fact the story of Prince Sujāti is taken from the xiaoyang 孝養,or filial devotion section of the Baoen-sūtra. The subject is the duty owed by a child to his parents in requitement of the blessings received from them. The merit earned by such requitement could be much greater than the original blessings (Mochizuki, 1973-74,p.4551).In the present painting, the side scenes on the right side show Sujāti’s filial devotion, to the extent of sacrificing his own body to feed his parents in a time of crisis. At the same time, the splendours and delights of the Pure Land of Sākyamuni are shown in the centre.The painting is virtually complete, including a painted valance and the plain sewn-on silk border, except for part of the centre foreground. Its rich, yet delicate colouring, though faded, is in places extraordinarily well preserved and shows the full splendour of Buddhist painting in the High Tang period. Despite this great beauty of colour and form, the painting has rarely been reproduced before (Matsumoto, 1937, Pl. 58; Stein, Thousand Buddhas, Pl. VI, part only), and then only in monochrome. It is a fine example of a more developed paradise scene than Buddha Preaching the Law (Pl.7). In order to help the faithful to visualize the splendours of the Pure Land into which they could hope to be reborn, the depiction includes a growing retinue of attendants about the Buddha and a magnificent setting, with musicians below and pavilions above, representing the delights and beauties of the Pure Land. The main part of the assembly is gathered on a platform rising out of a lotus lake: here infant souls, newly reborn, are seen on lotus flowers joining in adoration (Pl.8-8). To either side of this assembly are narrow side scenes set in landscapes. These represent episodes from three of the nine parts of the Baoen-sūtra. Each scene is identified by a cartouche inscribed with the relevant part of the story, so that the painting could easily be used for the instruction of the faithful.On the right side, from the top downwards, are seven episodes from the story of Prince Sujāti (Fig.22). The top scene, showing an official in red bowing before a king, is accompanied by a caption introducing the king of Vārānasī and his minister Rahula, who had conceived traitorous ambitions against him. In the second scene “a spirit appears out of space and warns the prince” of the impending attack by Rahula’s troops. Subsequent scenes show the flight of the king, his wife and son by a ladder from the walls of the city and their journey, taking with them a bag of provisions. In the sixth scene, when these have been exhausted, Sujāti is seen interposing between the king, with upraised sword, and the queen, whom he is about to kill. At the bottom, Sujāti, his body covered in wounds, is left crawling by the roadside as the king and his wife continue on their way. For the remainder of the story, see the side scenes to Stein painting 1(Figs.34, 35). The left side is divided between two stories: from the top downwards five cartouches describe part of the story of the deer mother, in which a deer conceives after drinking water in which a rishi had washed his clothes (Fig.21). Her child is shown as a woman, twice seen walking around the rishi’s cave, with lotuses springing from her footprints (Pl.8-7). From the bottom, another three scenes give part of the story of the Good and Wicked Sons, also from the Baoen-sūtra. At the bottom is the king of Vārānasī with one of his wives. The middle scene shows the childless king in front of a shrine performing ceremonies of supplication, as a result of which two sons were eventually born and named after the characters of the king’s first and second wives. The third scene, above this, shows the fulfilment of the Good Son’s vow to fill the land with treasures. The inscriptions supply more detail than the painter was able to show in these scenes, and in particular the lowest caption refers to the Good Son’s fast and to his mother’s intercession with the king to allow him to enter the ocean and cull its treasures in fulfillment of his vow.All of these scenes are set in landscape, with a few simple conventions to aid in the telling of the story. Thus the capital of the country of Vārānasī is represented by a city wall running across the narrow picture space, and a single pavilion, open at the front and with a flight of steps, serves both as the shrine where the king makes his vows (Fig.21, upper right)and as the setting, perhaps the palace, where a spirit appears to warn the king of his minister’s impending treachery(Fig.22,upper right).The other scenes are all appropriately set in landscapes which, by means of triangular slopes, zig-zag banks and flat spaces between, offer spaces for the incidents of the story. Some of the slopes, for example in the detail shown from the story of the deer (Pl.8-7), feature tall peaks and numerous plants and trees. The pointed forms of these peaks find counterparts both in the wall paintings and in some of the banners showing scenes from the life of the historical Buddha (Pl.39-1). Broad ink strokes are used to give further emphasis to the curved slopes and the vertical banks.In this painting the donors too are represented at the foot of these side scenes: on the right a nun and a novice, and on the left a woman, named as the lady Meng, kneeling and holding an incense burner. Her modest attitude, demure headdress and high-waisted robe all suggest a date still in the eighth century A.D.The architecture of the buildings above the paradise assembly reflects the appearance of Tang dynasty Buddhist temples, with a gatehouse and main hall on the central axis, connected by galleries to two-storeyed pavilions on either side of the main courtyard (Pl.8-3). The gateway itself is largely hidden by the Bodhi trees and canopy over the Buddha, but its great hipped roof, with the eaves seen from below and large “owl’s tail” finials, stretches across half the picture as a kind of canopy for the whole assembly. Beyond it, a raised and balustraded causeway leads to the main hall. This has just three bays. Simple brackets crown the columns, and straight struts provide additional support between them. The space within the hall revealed by the rolled-up bamboo screens is occupied by a low dais, beyond which is a painted screen.Although the central hall is quite small, its relationship with the gateway gives it a good deal of prominence. Both are seen from below so that it almost appears with the latter as a tall, two-storeyed building, a much larger version of the two-storeyed side pavilions. The latter display the same sequence of dark lower roof, balcony and upper roof with dark ridges and acroteria, but they are seen from above. On either side of the main axis, the open galleries have white-painted walls with square wooden windows and doors open to an interior beyond; there are lotus pedestals, six in all, along the galleries, but no figures on them. Above the roofs, the Buddhas of the Four Directions rise on cloud supports. Finally, the platform from which the entire complex rises is lined with panels of tilework elaborately decorated with floral patterns.The painting is endowed throughout with an extraordinary richness of colour in which dark and light are used to their best effect. Examples of the way in which the painter has achieved this can be seen in the main group of deities in the centre of the painting. Here, a black ground is used behind the figures, admirably setting off the rainbow hues of the haloes. Higher up, the black roofs of the gateway and side pavilions have a similar role. The haloes themselves are carefully orchestrated: among the lesser figures, the majority have plain colours (five blue, four green). They accord well with the prevailing tones in the whole painting. On them the petals (oblong or broad overlapping, respectively) are traced in fine white lines, now barely visible. The others (four with white cloud scrolls on a purple ground, and four with similar scrolls on orange and red) are evenly distributed to encircle the main figure. Only four are fully visible, while the others are partially obscured by the haloes of the three main figures. These in turn are far more elaborate. It is not necessary to describe them, as they are clear in the plates, but it may be observed that only that of the Buddha is adorned with a series of triangles appearing between the outer rows of petals. These triangles just touch to form a regular dentellation; in later paintings they are separated so as to appear more like barbed points, and their use gradually spreads from the main Buddha to the Bodhisattvas and eventually to lesser figures as well.The figures of the two Bodhisattvas, their compassionate faces seen from the front but gently inclined towards the central Buddha, invite comparison with wall paintings of the early Tang, such as in Cave 322(Dunhuang bihua, Pls.124-25). They retain a compactness of design although the richness of their adornments clearly indicates a somewhat later date for the painting on silk. In the foreground, the single dancing figure (Fig.20), poised between two garudas, sways and holds aloft long narrow scarves, striped in green and brilliant purple; these, too, are reminiscent of earlier wall paintings, e.g., Cave 220 (ibid., Pl.115).Bright colours such as purple and red are used in the garments of the minor Bodhisattvas and musicians, symmetrically disposed in the groups on either side.The silk of which the painting is made up consists of one full width of 55.5cm,and two half widths of about 27 cm each. The resulting painted area is thus slightly wider than that of Pl.7, and of course much longer, but the main figures are very much smaller, principally as a result of accommodating the narrative scenes on either side. By the careful manipulation of scale, however, the artist has been able to avoid any feeling of crowding.Finally, a feature which deserves special mention is the elegantly finished painted valance (Pl.8-2) and borders of flowers. The valance is elaborately made up with two double white streamers tied in symmetrical bows and dividing it into thirds. An actual example of such a valance, similarly divided by prominent streamers, is preserved in the Stein collection (Vol.3, Pl.8). Above the valance is a wide border of pairs of red florets edged in yellow with green and yellow leaf motifs. Similar but narrower borders with single florets separate the main paradise scene from the narrative side scenes. The present painted valance and the painted floral border above it are on a single separate piece of silk sewn onto the top edge of the painting. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1982:敦煌藝術中用壁畫或絹畫來表現佛經內容的繪畫,叫“變相”。此圖正是這種變相,即大方便佛報恩經變相。“報恩”的概念,正與中國傳統道德觀念中的“孝” 相符合,因此在中國很容易普及。事實上須闍提太子的故事即源自《報恩經•孝養品》,主旨講回報父母的恩德是子孫應盡的義務,回報父母的要比從父母那裏得到的多,是報恩中的美德(望月信亨《佛教大辭典》,1973-74,4551頁)。此作品右側邊緣表現的是須闍提太子的孝道故事,面對危機,將自己身體提供給父母解救饑餓。與此同時,中央則是描繪充滿光明歡樂的釋迦牟尼淨土。此畫相對完整,依然保留著畫著的帷幕及四周縫製的素色絹邊,只有前景中間部分稍有損壞。雖然褪了色,但某些部分仍然保留了豐富濃重的色彩,顯示了盛唐時期佛教繪畫的壯美。盡管此畫顔色、形態都非常美,但至今爲止,卻很少有將其製成圖版介紹的(松本榮一《敦煌畫研究》,1937,圖58,斯坦因《千佛洞》,圖6,僅是局部),並且也只是單色圖版。這是比上圖(圖7)《樹下說法圖》有更大發展的淨土圖的絕好的例子。為幫助信徒能夠看到希望往生的淨土的壯麗,本圖描述了佛和周圍衆多的眷屬,下端的歌伎、上端的樓閣,構成了壯觀的場面,用以描繪淨土的歡樂與華麗。聖衆的大半集中于蓮池中的寶臺上,代表再生靈魂的化生童子坐在蓮花上合掌禮拜,(圖8-8)。在聖衆兩側狹窄的邊緣,描繪有山水爲背景的故事圖,《報恩經》所記載的九段故事,有三段被描繪於此。各場景內容可以據長方形榜題來確認,這樣這幅畫可以很容易地實現對信徒的教化。右側邊緣,從上到下繪有七段須闍提太子的故事(參見Fig.22)。最上段描繪的是身著紅衣的大臣參拜大王,附有“波羅奈國大王和心生惡逆的大臣羅睺” 的標題。第二段是警告羅睺欲派兵馬襲擊的“虛空神祗的飛來”場面。與此相接的是大王、夫人和太子在城牆上架梯逃亡,以及攜帶食糧長途跋涉的場面。第六段是,食糧斷盡,大王舉起劍欲殺妃子時,須闍提太子橫插其間的場面。最下段描繪的是,受傷的須闍提太子留在道旁緩慢地爬行,大王和夫人則繼續旅程的場面。有關故事的剩餘部分,可以參看斯坦因繪畫1(參看Figs.34,35)。左側邊緣(參照單色圖版第21圖)分爲兩段故事,上方五段榜題記述《鹿母本生》的一部分,是鹿飲了仙人洗衣服的水而妊娠的故事(參看Fig.21)。鹿所産下的孩子長成婦人,用了兩個場面來描繪當她繞行仙人所住洞窟時,足下盛開了蓮花(參看圖8-7)。最下段表現的是《報恩經》中的善友太子、惡友太子故事的三個場面。下段中繪有波羅奈國王和他一位夫人,中間描繪沒有子嗣的大王在神殿前做祈願儀式,結果國王得到二個孩子,針對他們各自不同的性格,將第一夫人的孩子名爲善友,第二夫人的孩子名爲惡友。第三段是善友太子將財寶填滿國庫的誓願得到了實現的場面。長方形榜題上詳細記述著繪畫中未表示的內容,特別是最下段的榜題,記述著善友太子絕食、母后爲了使太子實現得到摩尼寶珠的誓願,勸解大王同意他赴大海。所有這些場面是在山水畫間展開的,爲了使場面更易理解,多加有極其簡單的象徵性的事物。諸如把波羅奈國的國都描繪爲橫穿狹窄畫面的城壁,國王施願的神殿(參看Fig.21,右上角)、神祗警告大臣即將叛逆而出現的場所(參看Fig.22,右上角),大概是宮殿,統統用正面入口和一段臺階來表示。山水畫的其它場景設計也非常恰當,三角形山丘與“Z”字形岸邊之間的空間,用來安排故事情節。一些山丘,如《鹿母本生》的細部(參看圖8-7)中,山的尖頂、無數的草木都很引人注目。在壁畫和反映佛傳內容的幡畫(參看圖39-1)中均有不少極為類似的尖頂山。爲了強調山凹處和峭立的河岸等,採用了較粗的墨線。此幅繪畫中,供養人像繪在兩邊緣最下端。右邊有比丘和比丘尼,左邊是“孟”姓的婦人,跪持帶柄香爐。從婦女恭恭敬敬的神態以及文雅的髮髻、高胸的衣裳等看,該繪畫的年代仍是8世紀。淨土上方的建築物構造爲中軸線上的門和中堂、配于中庭兩端的二層樓等,都有回廊連接,體現出唐時期佛教寺院的外觀(參看圖8-3)。門前的大部分被佛上方的華蓋和菩提樹遮住,仰視狀態的軒和大鴟尾攏於屋脊的巨大屋頂,橫跨著畫面的大半部分,猶如是全體聖衆的華蓋一般。其上方描繪的是通向中堂具有勾欄的臺階。中堂有三間,柱頂有簡單的斗栱,中間可以望見表示進深的數根柱子。中堂前面的竹簾上卷,內部有須彌壇,其旁有繪畫的隔扇。中堂極小,但從與之相連的門上卻感覺不出。因爲門和中堂都被描繪成從下往上仰視的形態,與宛如擴大了的兩翼的二層樓,看似是一體的建築物。這是因爲兩翼樓閣的的配色,一層和門樓的屋頂採用了相同的黑色,二層的勾欄配合中堂的勾欄,二層的屋頂和中堂的屋頂相同,都配有同樣帶黑邊的鴟尾。但在構圖上,樓閣卻是表現爲從上向下俯瞰的狀態。中軸線左右兩邊連綿的回廊,內側無圍牆,外側牆壁塗成白色,處處顯現有向內打開的方形木窗和門。回廊中擺放著蓮花座,共六個,上面並無乘坐者。屋頂上方,有代表四個方向的四方佛乘坐在雲彩上。最后,寶壇平地而起,上面貼有一層層非常美麗的花磚。此繪畫巧妙地運用了顔色的濃淡對比變化,顯現出極其豐富的色彩,以達到最佳效果。仔細看畫面中央的一群聖像,便可窺見繪畫作者使用色彩的理念。諸尊背景採用黑色,使背光的繁多顔色更加顯眼奪目,上方的門樓和側樓屋頂所採用的黑色亦起著同樣作用。諸尊背光色彩也非常細心地考慮其相互之間的協調:小尊背光多爲單色(五例青色,四例綠色),整體畫面的色調和諧均勻。背光上用白線繪著絢麗的紋樣(橢圓形狀和寬幅的重瓣形狀),但由於已經脫落,現在幾乎無法辨認。其他小尊的背光(紫色底子上有白色卷雲紋樣的四例,橙色和赤色底子上有同樣卷雲紋樣的四例),等距離地環繞在主尊的周圍。其中,能看見全身的只有四尊,其他被主要的三尊背光遮住了一部分。三尊主尊的背光並不精致,圖版中可見背光明亮,無需詳細說明。值得注意的是如來背光外周連接著的三角形裝飾。三角形互相銜接,有規律地排列著。但隨著時代的後移,每一個三角形都獨立存在,形狀更尖,使用範圍也從如來依次擴大到菩薩和周圍的諸小尊。脅侍的二菩薩深懷慈悲地面向前方,但略微傾向中央的如來,對比第322窟(參照《敦煌壁畫》圖124、125)等初唐時期的壁畫,從裝飾的豐富,簡潔的圖樣看,壁畫的年代不可能比絹畫晚多少年。前景中,在二隻迦陵頻伽之間,一位舞伎在空中舞動著綠、紫兩色飄帶翩翩起舞(參見Fig.20),這讓人想起第220窟(參見《敦煌壁畫》圖115)等早期壁畫中畫面左右兩側對稱的諸像,小菩薩或樂伎穿著鮮豔的紫色和紅色服裝。此幅絹畫由一幅寬55.5cm的絹和兩幅寬約27cm的半幅絹構成。所以畫面比圖7稍寬,當然縱向更長。但兩邊插入了故事畫,主要部分的諸尊則變得略小。然而藝術家巧妙處理了比例關係,避免了擁擠的感覺。最後要特別指出的一點是,極具雅趣的繪製的垂幕和花柄紋樣帶(參見圖8-2)。細心描繪的垂幕,配有兩根左右對稱的白色蝴蝶結飄帶,將整體分成三段。這種垂幕在斯坦因收集品(參見第3卷圖8)中存有實物,和這個垂幕一樣,有飄帶裝飾,把整體分爲三段。垂幕的上面有很寬的紋樣帶,紋樣是每兩朵有黃色邊緣的紅色小花,與綠和黃色葉子的組合。中央淨土圖與兩側故事畫的界限則是只有一朵同樣雅致的小花的窄幅紋樣帶。上部的垂幕和紋樣帶是繪在縫於畫面上端的另一絹子上。

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)