Period:Tang dynasty Production date:7thC-8thC (circa)

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha sun/moon bird 佛 (Chinese) 日/月 (Chinese) 鳥 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 45 centimetres Width: 43 centimetres

Description:

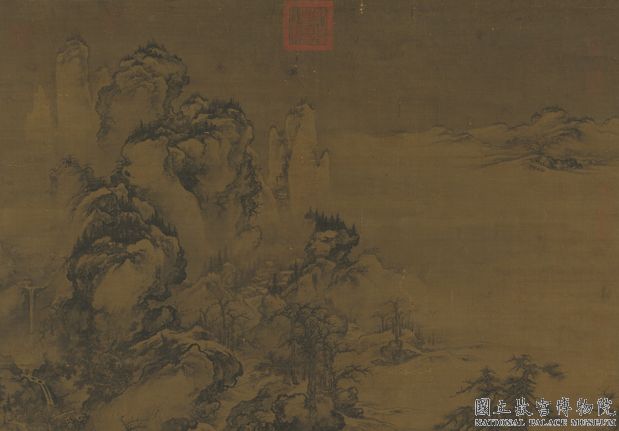

Painting fragments showing a standing Buddha touching the sun disc, with a cockerel. To the Buddha’s right is a blank cartouche. Some of the fragments were originally registered as OA 1919,0101,0.58. Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.51.2-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_IMG_9751.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.51.2-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00339152_001.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1983:This painting, as related in the Introduction to Vol. 1, has for over fifty years been divided between the British Museum and the National Museum of India. It is among the most important of all those in the collection, since it is an example of the kind of record brought back from India by travelling monks, showing the most famous images of Buddhism. This is not to say that this painting was itself painted there-rather it is a composite picture bringing together many images from different places. Many of them, in fact, have associations with Khotan, and even with Gansu, rather than with India directly. Nor is the painting alone in providing such a repertoire of images from India and Khotan: Pelliot’s photographs, published in 1931, show similar collections of famous images as part of the ceiling decoration in Caves 231 and 237, and on a whole wall in Cave 220 (Grottes, Pls. CLXⅧ,CLXXⅥ,CⅪ). In Cave 231 there are thirty-five figures on the four sloping faces of the ceiling over the main niche, each figure with an inscription which has been recorded by Xie Zhiliu 謝稚柳(Dunhuang yishu xulu 敦煌藝術敘錄,pp. 103-05). Some thirty-five figures are also visible in Pelliot’s Pl. CⅪ, showing the south wall of Cave 220 as it was at the time of his visit. Unfortunately the inscriptions were not recorded by Xie Zhiliu.In the early 1940s this cave was found to have splendid and well-preserved paintings of the early Tang under these thirty-five figures which dated from the Five Dynasties. The later paintings were sacrificed to reveal the early Tang compositions beneath them. Pelliot’s photograph (also Lo Archive, no. 220-7), therefore, is all that remains as a record of them.Like the lost wall painting of Cave 220, the silk painting originally had rows of images one above another. Its present divided state and the severe damage and losses it has sustained make it a difficult painting to assess, and these difficulties have led to its inclusion in the present volume, rather than in the first volume where by its probable date it should properly belong.A consideration of the physical state of the painting may help in forming some idea of its original appearance. In the first place it is necessary to understand that the mounting (at the time of writing) of the British Museum portion is totally misleading. Professor Alexander Soper’s excellent article “Representations of Famous Images at Tun-huang” (1964-65, pp. 349-64) shows this mounting in his Fig. 2, and the New Delhi portion in Fig. 1. Only Pl. LXX in Serindia shows the largest British Museum fragment in its correct relation above the New Delhi portion. For this reason it has seemed best, in the monochrome plates to this volume, to present the British Museum fragments separately, and to add a drawing which shows how several smaller misplaced fragments should be arranged (Fig. 9d). As this volume goes to press, remounting of the fragments is in progress. A more comprehensive reconstruction and study of the whole painting must await an opportunity of seeing the New Delhi portion and the possible identification of further fragments. For the present a brief description must suffice.The whole painting consisted of four rows of images, here referred to as A, B, C and D, the figures executed in outline but with a certain amount of ink shading and colour ornamentation. Cartouches of various shapes and sizes were fitted in as the seated or standing figures they described would allow. The largest British Museum fragment from the top of the painting (Fig. 9a) also has a very small piece of purple silk border, which defines the left edge of the painting. The fragment shown in Pl. 11 similarly similarly shows traces of the right-hand border, and may also come from the top of the painting. If it does, then the painting was originally made up of approximately three and a half widths of silk, the seams being indicated by dotted lines in Fig. 9d. No seam is present in Pl. 11, so there must have been a complete width of silk at the right edge of the painting.Below, the principal fragment assigned to New Delhi (Stein, Thousand Buddhas, Pl. ⅪⅤ) consists of three rows of images, principally in their correct relation to one another, except for some very small fragments and one seated figure which has been moved from row C to row B. Its present place in row Brightly belongs to the fragments shown in Fig. 9b. They too show that most of the right-hand side of the painting is still missing. Finally, one large fragment in the British Museum (Fig. 9f), until now mounted upside down, has, as already described in Serindia, part of a female donor in seventh to eighth century dress next to the ruled space for a dedicatory inscription. The most likely position for this inscription which surely had a male donor on the other side and possibly other subsidiary donors as well, is at the bottom, immediately below the four rows of images. I have assumed this in suggesting the possible original size of the painting as about 3 m by 2 m; thus it can be seen that in size as well this was one of the most important paintings discovered by Stein. It has to be hoped that examination of any further fragments will help to complete the reconstruction. We should now turn to the individual figures shown in the British 9a (and the drawing Fig. 9d) shows, first of all, two standing Buddhas, each with a canopy. Though fragmentary, enough can be made out of the two figures to determine that one is in vitarka – mudra; the other grasps the hem of the robe with his left hand while the right hand is lost. But no explanation has been offered, though dunhuang Cave 237 likewise has “two Buddhas side by side”. Separated from the two Buddhas by a tall narrow cartouche (no longer legible) is a large figure of a Buddha in a red robe, seated with legs pendent, under a larger canopy. Again, no explanation can be offered to identify this figure. To the right again, there appears a pair of men holding a ladder and gazing upwards at a missing image. A tiny fragment of bare feet on the other side of the images is all that remains of the rest, but the ladder is a distinctive clue to a story of a thief who wished to steal the jewel from the forehead of an image; although in longer accounts the ladder was never quite long enough, “all accounts agree that eventually the statue bent over out of pity to offer the jewel” (Soper, 1964-64, p. 363).The next fragment, at the right end of the top row, is that shown in colour (Pl. 11), depicting first of all a garlanded Bodhisattva, with a double row of Buddhas in his aureole, and then a standing Buddha with his arm raised and supporting the sun, in which is seen a phoenix. Soper has connected this with the “image shown pointing to the sun and moon” found in three of the caves, perhaps Sakyamuni after the defeat of Mara.This completes the first row of figures. The second row, B, begins at the left in the New Delhi portion with Gautama at the time of his illumination at Bodh Gaya. Next, also in India, is a standing figure, the aureole filled with busts of Buddhas, representing the miraculous multiplication of Buddha-bodies by Sakyamuni at Sravasti. Third in row B is the seated figure shown in Fig. 9b, with legs pendent and multiple figures in the aureole, with a top segment of musicians. Next to it is the lower half of a standing Buddha in a red robe. Nothing remains to identify it, nor can any other fragments be placed with certainty in this row.The New Delhi portion continues in row C, first with four smaller figures, then a Buddha seated on a dragon throne, followed by a standing image identified by the small deer at the top (and by a cartouche preserved separately at the British Museum) as the “Image in the Deer Park in the country of Varanasi in middle India”. Similar inscriptions are to be found in Caves 231 and 237 at Dunhuang. After this should come the seated image at present mounted in the row above in New Delhi, with crescent moons in the nimbus, with next to it a small fragment, two men in coats and top-boots, wrongly mounted in the British Museum next to the ladder scene.Row D is also in the New Delhi portion. It features standing figures in rocky settings: Avalokitesvara on Mt. Potalaka and Sakyamuni preaching at the Vulture Peak. The inscription and donor figures probably came below this, as row E.In this way all of the British Museum fragments have been accounted for, except for two Lokapalas standing side by side, of which only a very narrow fragment showing a hand grasping a trident and another hand holding up a stupa (Fig. 9c) remain. There is also a separate tiny fragment of a pennant. There is of course no way at present to determine the original position of these fragments, other than that, as the left side and centre of the painting are virtually intact, they must be from the missing right side. If further fragments from the painting prove to be identifiable, it may be possible to reconstruct parts of this side as well. What can be seen at present already shows that the composition was presented in an orderly fashion: at least three of the figures in row A have canopies, while the figure holding the sun in Pl. 11 also appears appropriate to the top of the painting; at the bottom, Avalokitesvara and Sakyamuni are in substantial rocky settings that give stability to the whole. One would expect this lowest row, D, to have one more figure in a rocky setting. Moreover, in rows B and C there is already a certain measure of symmetry, seen in the regular alternation of seated and standing figures, giving five large scenes originally in each row. One is left with the feeling that this was a well-ordered and monumental composition, not just a lining-up of images in random order.Several interesting points emerge when we consider the style of these fragments and their iconographical origins. For the latter the reader will have to refer to Professor Soper’s article, already mentioned above. Here it must suffice to say that while some of the figures show images famous in India, others have strong associations with Khotan. Similarly, while the drapery of the figures shows close affinities with the art of Gandhara (and many details of the jewellery can be traced to Indian or Gandharan prototypes also), still other details seem to have been borrowed from earlier Chinese Buddhist art, such as the celestial musicans, following Northern Wei, surrounding one of the New Delhi figures: Soper, noting this, has shown that “the images shown were not intended to be exclusively Indian at all, and were in fact faithfully recorded” (Soper, 1964-65, p. 352).Looking at the elegant outline drawing of the figures, we can see that it is chiefly dependent on a subtle continuous line, not greatly modulated. The canopies of the three first figures in row A can be compared with canopies of the early Tang at Dunhuang, a domed form with curving ribs recurved at ends. From these hang small bells, with a little shading or highlight and a tongue hanging beneath each. In later paintings from Dunhuang these “tells” lengthen and take the form of tassels with horizontal coloured bands. Other eighth century stylistic characteristics can be seen in the facial delineation of the figures, especially of the mouth, comparable to those of the figures in Buddha Preaching the Law (Vol. 1, Pl. 7); or in the way in which the petals of the lotus thrones are strongly modeled and in some cases elaborately decorated with small leaf sprays in red.Thus, in these severely damaged fragments, there is still a monument of outstanding importance and of early date, which can furnish much information on the lost images, not only of the similar painting once in Cave 220, but of Khotan, once a leading centre of Mahayana Buddhism, and of India, the land of its birth. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1983:正如第1卷的序文中提到的,此畫的所有斷片在50年前,大英博物館和新德里國立博物館間分割斯坦因收集品的時,被分藏到兩個博物館。此畫的一部分斷片也在聖彼得堡艾爾米塔什美術館裏发现。此作品是雲遊僧從印度帶回的佛教著名瑞像的一個例證,是斯坦因收集的敦煌畫中最爲珍貴的作品之一。此畫本身并不產生於印度,可能是採納了各地佛像样式的複合式作品,多数像與其說與印度有联系,不如看作是與和闐以及中國甘肅地區有直接關係。這不是唯一採納印度或和闐的各種佛像樣式而製作的範例,在1931年出版的伯希和《石窟圖錄》中,有第231窟和237窟天井畫的部分和第220窟的整壁畫上描繪的相同的瑞像圖(參照《石窟圖錄》圖版168、176、111)。據謝稚柳的記述,第231窟西壁佛龕的龕頂四周描有三十五身像,每一像都附有文字(參照《敦煌藝術敘錄》103~105頁)。同樣的三十五身像,在伯希和訪問的當時第220窟南壁的照片(《石窟圖錄》圖版111)中也可見到,但遺憾的是,謝稚柳沒有記錄有關文字。1940年初,發現第220窟的下層留有華麗的初唐淨土圖,在剝落了上層的五代以後的壁畫的同時,南壁的瑞像圖也被破壞了。所以,現在與那瑞像圖有關的資料,除了伯希和和羅寄梅(參照No.220-7)的照片外,沒有留下其他資料。與現已不存的第220窟壁畫的瑞像圖一樣,當初此絹繪的尊像也是由幾段重疊而成的。現在作品被分割成幾件的同時,損傷以及殘缺嚴重,對此畫的評價變得更難。這些困難,使得根據年代排列,它應屬本全集的第1卷組,卻被放到了現在的位置。觀察各斷片的物理形狀,是獲取此畫結構原形的重要參考依據。首先,關於大英博物館收藏的部分,必須知道現在(撰寫該稿的時間)的裝裱是完全錯誤的。Alexander Soper教授的《敦煌瑞像圖》中將這錯誤的裝裱作爲了插圖2,與插圖1的新德里國立博物館收藏的部分一同刊載。而《西域》圖版70中,是把大英博物館最大的斷片放在新德里國立博物館收藏部分的上面,正確顯示出了它的位置關係。根據以上的分析,本卷Fig.9中,將大英博物館收藏的各斷片從現在的裝裱剝離,分開收錄的同時,還附帶列出了將錯誤部分糾正過來的勾勒圖。至於更廣範圍的復原以及對整圖的研究,不得不等見到新德里國立博物館收藏的諸斷片的實物,再與艾爾米塔什美術館收藏的斷片进行比較以后,目前只能記錄其概略。 畫面由下頁插圖中所標的ABCD四塊組成,諸像有墨線的輪廓,僅加墨暈和彩色。並且對應坐像和立像的不同而産生的空間變化,插入的長方形題記欄的形式和尺寸也適當改變。大英博物館收藏的最大斷片(參照Fig.9a)中,上端只留下很小的紫色絹邊,從而推定了當時構成了畫面左上部。同樣,圖11的斷片中也看到右端的絹邊痕迹,推斷當時處於畫面右上部位置。如果這種推斷是正確的,那麽當時畫面的幅寬是連接了三幅半絹子而成的寬幅作品,絹子可能是在Fig.9d中用點線標識的位置上縫合的。另外,圖11的斷片中看不出綴接的針眼,所以畫面的右側使用了一幅絹子。從下方B到D的三塊中,出現的是新德里國立博物館收藏的此畫主要部分(參照《千佛洞》圖版14:下一頁的插圖)的諸尊。新德里國立博物館現在的裝裱中所見的諸尊位置關係大致準確,但極小的若干斷片和本來應屬C塊的一身坐像被移到了B塊中,現在那像的位置上,應放置Fig.9b所表現的大英博物館的斷片。如此整理,可知構成畫面右方的大部分斷片已遺失。然而引人注意的是,在上下顛倒裝裱的大英博物館收藏的大斷片(Fig.9f圖)中,正如在《西域》中指出的,功德題記欄的旁邊,可見一部分身著7~8世紀衣裳的女供養人像。作爲放置這題記欄的最合適位置的第四塊尊像群的正下方,即畫面的最下端,女供養人像的對面畫有男供養人像,他們各自的背後可能還跟隨著很多供養人。如此可見,當時此畫的尺寸可達到高3米、寬2米。從大小這一點上,也可以說它是斯坦因攜回的敦煌繪畫中最值得重視的作品之一。通過若干斷片類別的觀察,有望完成該繪畫的復原工作。這裏再次回到大英博物館的斷片,想對錯誤裝裱的每個像進行推斷,並排出其正確的位置。最初在Fig.9a中揭示的斷片(其勾勒是9d圖),左端顯現華蓋下面並排站立的兩身佛,殘損嚴重,能確認其中一身結說法印,另一身的右手殘缺,左手抓衣端,沒有說明文,但和敦煌第237窟所見的“二佛並立”同趣。這兩佛像間用長方形題箋(字迹暗淡,無法釋讀)隔開的右側,可見大型華蓋下面著紅色衣服的倚像,此像也未留任何能比定的說明。再右側,有撐梯子的兩個男人,他們仰望上部描繪已遺失的佛像。相當於此部分的內容,應來自佛像對面,除了畫有裸足的小斷片外,任何也沒有留下,但梯子提供有力的線索,可知畫在這裏的是小偷盜竊佛像額頭上的寶石的故事。故事中講,佛像過大而梯子無法靠近,而“結局是佛像生憐憫心,俯首讓寶石取下”(參照《敦煌瑞像圖》363頁)。接下來是在圖11中刊载的斷片,當時它應在畫面最上段的右邊。左側是配飾兩層化佛背光,頸上懸挂花綵的菩薩。右側繪有舉右手捧日輪的佛立像,日輪中有鳳凰。Soper教授將其解釋爲在敦煌三個窟所見的,可能是表現釋迦降魔後的“指日月像”。以上第一塊(A塊)結束,轉到第二塊(B塊)。左端是新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片,表現的是佛陀在菩提迦耶成道。其右邊也是新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片,表現舍衛城大神變,是背光裏繪入很多佛像的釋迦立像。接著它的第三個像是在Fig.9b中所揭示的倚像,背光內有很多佛頭,背光外插入飛天。其右方可見赤衣佛立像的下半身,但找不到放置此塊的位置或綴接它的其他斷片類。新德里國立博物館的斷片也是接續C塊,最初是四身小像,次是坐在龍座上的佛陀。連接右邊的立像,從上方所描繪的小鹿和大英博物館分藏的這部分的長方形題簽所記的說明判斷,是中印度靠近波羅奈斯的鹿野苑初轉法輪像。在敦煌第231窟和第237窟的壁畫中也見到同樣的記述。此像的下面,是新德里國立博物館現在裝裱的上段位置,有頭光配飾三日月的坐像,大英博物館所藏現在錯誤粘貼在梯子部分右側的,只認出兩個人物的裳裾和長靴的斷片,應該是来自此像的右側。D塊還在新德里國立博物館,是以岩山做背景的立像斷片,那是描繪補陀洛山的觀音和在靈鷲山說法的釋迦。其下即E段,可能是題記欄和供養人像。以上只是涉及大英博物館的斷片類的大致解釋,另外,還有兩身並立的天王像,各自殘留只可辨認出一隻手、三叉戟、塔的一部分的極小的斷片(參照Fig.9c),現在無法確認當時這些斷片的正確位置,對畫面左邊部分和中央部分的敍述已經大體接近,因此只能認爲它們是殘缺嚴重的右邊部分的,如能發現證明該繪畫的斷片,才有可能復原這部分。在此,整理總結迄今發現的有關構圖,目前的狀況是,A塊中,有華蓋的尊像至少能確認三身,圖11中捧日輪的佛可能也是畫面上端A塊的內容。另外,D塊中觀音和釋迦的描繪以堅固的岩山爲背景,給予了整體構圖的穩定感。此塊中可能還有一身以岩山爲背景的像。再,B以及C塊中,當時是坐像和立像交錯排列的五身像,而且可能也是接近左右對稱的結構。總之,該作品給我們留下的印象是,不只是尊像的羅列,而且還是有秩序的進行記錄的。如果對所見的這些斷片中各像的風格和圖像的原型進行考察,可接觸到很多有趣的問題。關於圖像的問題,可以參考上述Soper教授的論文。有幾身像顯示出印度著名像的形象,這裏只打算留意其餘的有很強和闐影響的像。同樣,相對於尊像衣紋的線條與犍陀羅藝術有很深聯繫(寶石和裝飾部分可辨出是印度或犍陀羅的影響)的其他部分,如新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片中,有繼承北魏風格的飛天,也有採納早期中國佛教美術的表現方式。Soper教授也注意到這一點,“這些諸像沒有試圖表現印度式繪法,而是有意對實物進行忠實的記錄”(參照《敦煌瑞像圖》352頁)。注意諸像優美的輪廓線,可發現連貫精致的勾勒線幾乎沒有大的晃動。A塊最初三身像的華蓋,實際可與敦煌初唐時期窟中殘留的支撐肋材末端翻翹成拱形的華蓋做比較。那些華蓋邊緣挂小的吊鍾形裝飾,稍加暈染和高光的同時,下方添加了舌狀的描繪。更晚期的敦煌畫中,這種“吊鍾形裝飾”變得很長,平行的色線成穗形。體現此畫8世紀作品的風格特色,其他還可舉出諸尊臉部的描繪。特別是嘴部,可與《樹下說法圖》(參照第1卷圖7)的諸像做比較。另外蓮華座的蓮瓣表現得非常結實,時而還加入紅色葉脈的華麗裝飾,可窺出此畫是早期的範例。綜上所述,此作品儘管殘損極其嚴重,但對於曾經存在于敦煌第220窟的同趣的繪畫、保存於大乘佛教指導中心和闐以及佛教發祥地印度等地現在已經遺失的佛畫來說,這畫能使人窺到很多東西,从這一點上它是非常重要的遺物。

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha sun/moon bird 佛 (Chinese) 日/月 (Chinese) 鳥 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 45 centimetres Width: 43 centimetres

Description:

Painting fragments showing a standing Buddha touching the sun disc, with a cockerel. To the Buddha’s right is a blank cartouche. Some of the fragments were originally registered as OA 1919,0101,0.58. Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.51.2-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_IMG_9751.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.51.2-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00339152_001.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1983:This painting, as related in the Introduction to Vol. 1, has for over fifty years been divided between the British Museum and the National Museum of India. It is among the most important of all those in the collection, since it is an example of the kind of record brought back from India by travelling monks, showing the most famous images of Buddhism. This is not to say that this painting was itself painted there-rather it is a composite picture bringing together many images from different places. Many of them, in fact, have associations with Khotan, and even with Gansu, rather than with India directly. Nor is the painting alone in providing such a repertoire of images from India and Khotan: Pelliot’s photographs, published in 1931, show similar collections of famous images as part of the ceiling decoration in Caves 231 and 237, and on a whole wall in Cave 220 (Grottes, Pls. CLXⅧ,CLXXⅥ,CⅪ). In Cave 231 there are thirty-five figures on the four sloping faces of the ceiling over the main niche, each figure with an inscription which has been recorded by Xie Zhiliu 謝稚柳(Dunhuang yishu xulu 敦煌藝術敘錄,pp. 103-05). Some thirty-five figures are also visible in Pelliot’s Pl. CⅪ, showing the south wall of Cave 220 as it was at the time of his visit. Unfortunately the inscriptions were not recorded by Xie Zhiliu.In the early 1940s this cave was found to have splendid and well-preserved paintings of the early Tang under these thirty-five figures which dated from the Five Dynasties. The later paintings were sacrificed to reveal the early Tang compositions beneath them. Pelliot’s photograph (also Lo Archive, no. 220-7), therefore, is all that remains as a record of them.Like the lost wall painting of Cave 220, the silk painting originally had rows of images one above another. Its present divided state and the severe damage and losses it has sustained make it a difficult painting to assess, and these difficulties have led to its inclusion in the present volume, rather than in the first volume where by its probable date it should properly belong.A consideration of the physical state of the painting may help in forming some idea of its original appearance. In the first place it is necessary to understand that the mounting (at the time of writing) of the British Museum portion is totally misleading. Professor Alexander Soper’s excellent article “Representations of Famous Images at Tun-huang” (1964-65, pp. 349-64) shows this mounting in his Fig. 2, and the New Delhi portion in Fig. 1. Only Pl. LXX in Serindia shows the largest British Museum fragment in its correct relation above the New Delhi portion. For this reason it has seemed best, in the monochrome plates to this volume, to present the British Museum fragments separately, and to add a drawing which shows how several smaller misplaced fragments should be arranged (Fig. 9d). As this volume goes to press, remounting of the fragments is in progress. A more comprehensive reconstruction and study of the whole painting must await an opportunity of seeing the New Delhi portion and the possible identification of further fragments. For the present a brief description must suffice.The whole painting consisted of four rows of images, here referred to as A, B, C and D, the figures executed in outline but with a certain amount of ink shading and colour ornamentation. Cartouches of various shapes and sizes were fitted in as the seated or standing figures they described would allow. The largest British Museum fragment from the top of the painting (Fig. 9a) also has a very small piece of purple silk border, which defines the left edge of the painting. The fragment shown in Pl. 11 similarly similarly shows traces of the right-hand border, and may also come from the top of the painting. If it does, then the painting was originally made up of approximately three and a half widths of silk, the seams being indicated by dotted lines in Fig. 9d. No seam is present in Pl. 11, so there must have been a complete width of silk at the right edge of the painting.Below, the principal fragment assigned to New Delhi (Stein, Thousand Buddhas, Pl. ⅪⅤ) consists of three rows of images, principally in their correct relation to one another, except for some very small fragments and one seated figure which has been moved from row C to row B. Its present place in row Brightly belongs to the fragments shown in Fig. 9b. They too show that most of the right-hand side of the painting is still missing. Finally, one large fragment in the British Museum (Fig. 9f), until now mounted upside down, has, as already described in Serindia, part of a female donor in seventh to eighth century dress next to the ruled space for a dedicatory inscription. The most likely position for this inscription which surely had a male donor on the other side and possibly other subsidiary donors as well, is at the bottom, immediately below the four rows of images. I have assumed this in suggesting the possible original size of the painting as about 3 m by 2 m; thus it can be seen that in size as well this was one of the most important paintings discovered by Stein. It has to be hoped that examination of any further fragments will help to complete the reconstruction. We should now turn to the individual figures shown in the British 9a (and the drawing Fig. 9d) shows, first of all, two standing Buddhas, each with a canopy. Though fragmentary, enough can be made out of the two figures to determine that one is in vitarka – mudra; the other grasps the hem of the robe with his left hand while the right hand is lost. But no explanation has been offered, though dunhuang Cave 237 likewise has “two Buddhas side by side”. Separated from the two Buddhas by a tall narrow cartouche (no longer legible) is a large figure of a Buddha in a red robe, seated with legs pendent, under a larger canopy. Again, no explanation can be offered to identify this figure. To the right again, there appears a pair of men holding a ladder and gazing upwards at a missing image. A tiny fragment of bare feet on the other side of the images is all that remains of the rest, but the ladder is a distinctive clue to a story of a thief who wished to steal the jewel from the forehead of an image; although in longer accounts the ladder was never quite long enough, “all accounts agree that eventually the statue bent over out of pity to offer the jewel” (Soper, 1964-64, p. 363).The next fragment, at the right end of the top row, is that shown in colour (Pl. 11), depicting first of all a garlanded Bodhisattva, with a double row of Buddhas in his aureole, and then a standing Buddha with his arm raised and supporting the sun, in which is seen a phoenix. Soper has connected this with the “image shown pointing to the sun and moon” found in three of the caves, perhaps Sakyamuni after the defeat of Mara.This completes the first row of figures. The second row, B, begins at the left in the New Delhi portion with Gautama at the time of his illumination at Bodh Gaya. Next, also in India, is a standing figure, the aureole filled with busts of Buddhas, representing the miraculous multiplication of Buddha-bodies by Sakyamuni at Sravasti. Third in row B is the seated figure shown in Fig. 9b, with legs pendent and multiple figures in the aureole, with a top segment of musicians. Next to it is the lower half of a standing Buddha in a red robe. Nothing remains to identify it, nor can any other fragments be placed with certainty in this row.The New Delhi portion continues in row C, first with four smaller figures, then a Buddha seated on a dragon throne, followed by a standing image identified by the small deer at the top (and by a cartouche preserved separately at the British Museum) as the “Image in the Deer Park in the country of Varanasi in middle India”. Similar inscriptions are to be found in Caves 231 and 237 at Dunhuang. After this should come the seated image at present mounted in the row above in New Delhi, with crescent moons in the nimbus, with next to it a small fragment, two men in coats and top-boots, wrongly mounted in the British Museum next to the ladder scene.Row D is also in the New Delhi portion. It features standing figures in rocky settings: Avalokitesvara on Mt. Potalaka and Sakyamuni preaching at the Vulture Peak. The inscription and donor figures probably came below this, as row E.In this way all of the British Museum fragments have been accounted for, except for two Lokapalas standing side by side, of which only a very narrow fragment showing a hand grasping a trident and another hand holding up a stupa (Fig. 9c) remain. There is also a separate tiny fragment of a pennant. There is of course no way at present to determine the original position of these fragments, other than that, as the left side and centre of the painting are virtually intact, they must be from the missing right side. If further fragments from the painting prove to be identifiable, it may be possible to reconstruct parts of this side as well. What can be seen at present already shows that the composition was presented in an orderly fashion: at least three of the figures in row A have canopies, while the figure holding the sun in Pl. 11 also appears appropriate to the top of the painting; at the bottom, Avalokitesvara and Sakyamuni are in substantial rocky settings that give stability to the whole. One would expect this lowest row, D, to have one more figure in a rocky setting. Moreover, in rows B and C there is already a certain measure of symmetry, seen in the regular alternation of seated and standing figures, giving five large scenes originally in each row. One is left with the feeling that this was a well-ordered and monumental composition, not just a lining-up of images in random order.Several interesting points emerge when we consider the style of these fragments and their iconographical origins. For the latter the reader will have to refer to Professor Soper’s article, already mentioned above. Here it must suffice to say that while some of the figures show images famous in India, others have strong associations with Khotan. Similarly, while the drapery of the figures shows close affinities with the art of Gandhara (and many details of the jewellery can be traced to Indian or Gandharan prototypes also), still other details seem to have been borrowed from earlier Chinese Buddhist art, such as the celestial musicans, following Northern Wei, surrounding one of the New Delhi figures: Soper, noting this, has shown that “the images shown were not intended to be exclusively Indian at all, and were in fact faithfully recorded” (Soper, 1964-65, p. 352).Looking at the elegant outline drawing of the figures, we can see that it is chiefly dependent on a subtle continuous line, not greatly modulated. The canopies of the three first figures in row A can be compared with canopies of the early Tang at Dunhuang, a domed form with curving ribs recurved at ends. From these hang small bells, with a little shading or highlight and a tongue hanging beneath each. In later paintings from Dunhuang these “tells” lengthen and take the form of tassels with horizontal coloured bands. Other eighth century stylistic characteristics can be seen in the facial delineation of the figures, especially of the mouth, comparable to those of the figures in Buddha Preaching the Law (Vol. 1, Pl. 7); or in the way in which the petals of the lotus thrones are strongly modeled and in some cases elaborately decorated with small leaf sprays in red.Thus, in these severely damaged fragments, there is still a monument of outstanding importance and of early date, which can furnish much information on the lost images, not only of the similar painting once in Cave 220, but of Khotan, once a leading centre of Mahayana Buddhism, and of India, the land of its birth. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1983:正如第1卷的序文中提到的,此畫的所有斷片在50年前,大英博物館和新德里國立博物館間分割斯坦因收集品的時,被分藏到兩個博物館。此畫的一部分斷片也在聖彼得堡艾爾米塔什美術館裏发现。此作品是雲遊僧從印度帶回的佛教著名瑞像的一個例證,是斯坦因收集的敦煌畫中最爲珍貴的作品之一。此畫本身并不產生於印度,可能是採納了各地佛像样式的複合式作品,多数像與其說與印度有联系,不如看作是與和闐以及中國甘肅地區有直接關係。這不是唯一採納印度或和闐的各種佛像樣式而製作的範例,在1931年出版的伯希和《石窟圖錄》中,有第231窟和237窟天井畫的部分和第220窟的整壁畫上描繪的相同的瑞像圖(參照《石窟圖錄》圖版168、176、111)。據謝稚柳的記述,第231窟西壁佛龕的龕頂四周描有三十五身像,每一像都附有文字(參照《敦煌藝術敘錄》103~105頁)。同樣的三十五身像,在伯希和訪問的當時第220窟南壁的照片(《石窟圖錄》圖版111)中也可見到,但遺憾的是,謝稚柳沒有記錄有關文字。1940年初,發現第220窟的下層留有華麗的初唐淨土圖,在剝落了上層的五代以後的壁畫的同時,南壁的瑞像圖也被破壞了。所以,現在與那瑞像圖有關的資料,除了伯希和和羅寄梅(參照No.220-7)的照片外,沒有留下其他資料。與現已不存的第220窟壁畫的瑞像圖一樣,當初此絹繪的尊像也是由幾段重疊而成的。現在作品被分割成幾件的同時,損傷以及殘缺嚴重,對此畫的評價變得更難。這些困難,使得根據年代排列,它應屬本全集的第1卷組,卻被放到了現在的位置。觀察各斷片的物理形狀,是獲取此畫結構原形的重要參考依據。首先,關於大英博物館收藏的部分,必須知道現在(撰寫該稿的時間)的裝裱是完全錯誤的。Alexander Soper教授的《敦煌瑞像圖》中將這錯誤的裝裱作爲了插圖2,與插圖1的新德里國立博物館收藏的部分一同刊載。而《西域》圖版70中,是把大英博物館最大的斷片放在新德里國立博物館收藏部分的上面,正確顯示出了它的位置關係。根據以上的分析,本卷Fig.9中,將大英博物館收藏的各斷片從現在的裝裱剝離,分開收錄的同時,還附帶列出了將錯誤部分糾正過來的勾勒圖。至於更廣範圍的復原以及對整圖的研究,不得不等見到新德里國立博物館收藏的諸斷片的實物,再與艾爾米塔什美術館收藏的斷片进行比較以后,目前只能記錄其概略。 畫面由下頁插圖中所標的ABCD四塊組成,諸像有墨線的輪廓,僅加墨暈和彩色。並且對應坐像和立像的不同而産生的空間變化,插入的長方形題記欄的形式和尺寸也適當改變。大英博物館收藏的最大斷片(參照Fig.9a)中,上端只留下很小的紫色絹邊,從而推定了當時構成了畫面左上部。同樣,圖11的斷片中也看到右端的絹邊痕迹,推斷當時處於畫面右上部位置。如果這種推斷是正確的,那麽當時畫面的幅寬是連接了三幅半絹子而成的寬幅作品,絹子可能是在Fig.9d中用點線標識的位置上縫合的。另外,圖11的斷片中看不出綴接的針眼,所以畫面的右側使用了一幅絹子。從下方B到D的三塊中,出現的是新德里國立博物館收藏的此畫主要部分(參照《千佛洞》圖版14:下一頁的插圖)的諸尊。新德里國立博物館現在的裝裱中所見的諸尊位置關係大致準確,但極小的若干斷片和本來應屬C塊的一身坐像被移到了B塊中,現在那像的位置上,應放置Fig.9b所表現的大英博物館的斷片。如此整理,可知構成畫面右方的大部分斷片已遺失。然而引人注意的是,在上下顛倒裝裱的大英博物館收藏的大斷片(Fig.9f圖)中,正如在《西域》中指出的,功德題記欄的旁邊,可見一部分身著7~8世紀衣裳的女供養人像。作爲放置這題記欄的最合適位置的第四塊尊像群的正下方,即畫面的最下端,女供養人像的對面畫有男供養人像,他們各自的背後可能還跟隨著很多供養人。如此可見,當時此畫的尺寸可達到高3米、寬2米。從大小這一點上,也可以說它是斯坦因攜回的敦煌繪畫中最值得重視的作品之一。通過若干斷片類別的觀察,有望完成該繪畫的復原工作。這裏再次回到大英博物館的斷片,想對錯誤裝裱的每個像進行推斷,並排出其正確的位置。最初在Fig.9a中揭示的斷片(其勾勒是9d圖),左端顯現華蓋下面並排站立的兩身佛,殘損嚴重,能確認其中一身結說法印,另一身的右手殘缺,左手抓衣端,沒有說明文,但和敦煌第237窟所見的“二佛並立”同趣。這兩佛像間用長方形題箋(字迹暗淡,無法釋讀)隔開的右側,可見大型華蓋下面著紅色衣服的倚像,此像也未留任何能比定的說明。再右側,有撐梯子的兩個男人,他們仰望上部描繪已遺失的佛像。相當於此部分的內容,應來自佛像對面,除了畫有裸足的小斷片外,任何也沒有留下,但梯子提供有力的線索,可知畫在這裏的是小偷盜竊佛像額頭上的寶石的故事。故事中講,佛像過大而梯子無法靠近,而“結局是佛像生憐憫心,俯首讓寶石取下”(參照《敦煌瑞像圖》363頁)。接下來是在圖11中刊载的斷片,當時它應在畫面最上段的右邊。左側是配飾兩層化佛背光,頸上懸挂花綵的菩薩。右側繪有舉右手捧日輪的佛立像,日輪中有鳳凰。Soper教授將其解釋爲在敦煌三個窟所見的,可能是表現釋迦降魔後的“指日月像”。以上第一塊(A塊)結束,轉到第二塊(B塊)。左端是新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片,表現的是佛陀在菩提迦耶成道。其右邊也是新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片,表現舍衛城大神變,是背光裏繪入很多佛像的釋迦立像。接著它的第三個像是在Fig.9b中所揭示的倚像,背光內有很多佛頭,背光外插入飛天。其右方可見赤衣佛立像的下半身,但找不到放置此塊的位置或綴接它的其他斷片類。新德里國立博物館的斷片也是接續C塊,最初是四身小像,次是坐在龍座上的佛陀。連接右邊的立像,從上方所描繪的小鹿和大英博物館分藏的這部分的長方形題簽所記的說明判斷,是中印度靠近波羅奈斯的鹿野苑初轉法輪像。在敦煌第231窟和第237窟的壁畫中也見到同樣的記述。此像的下面,是新德里國立博物館現在裝裱的上段位置,有頭光配飾三日月的坐像,大英博物館所藏現在錯誤粘貼在梯子部分右側的,只認出兩個人物的裳裾和長靴的斷片,應該是来自此像的右側。D塊還在新德里國立博物館,是以岩山做背景的立像斷片,那是描繪補陀洛山的觀音和在靈鷲山說法的釋迦。其下即E段,可能是題記欄和供養人像。以上只是涉及大英博物館的斷片類的大致解釋,另外,還有兩身並立的天王像,各自殘留只可辨認出一隻手、三叉戟、塔的一部分的極小的斷片(參照Fig.9c),現在無法確認當時這些斷片的正確位置,對畫面左邊部分和中央部分的敍述已經大體接近,因此只能認爲它們是殘缺嚴重的右邊部分的,如能發現證明該繪畫的斷片,才有可能復原這部分。在此,整理總結迄今發現的有關構圖,目前的狀況是,A塊中,有華蓋的尊像至少能確認三身,圖11中捧日輪的佛可能也是畫面上端A塊的內容。另外,D塊中觀音和釋迦的描繪以堅固的岩山爲背景,給予了整體構圖的穩定感。此塊中可能還有一身以岩山爲背景的像。再,B以及C塊中,當時是坐像和立像交錯排列的五身像,而且可能也是接近左右對稱的結構。總之,該作品給我們留下的印象是,不只是尊像的羅列,而且還是有秩序的進行記錄的。如果對所見的這些斷片中各像的風格和圖像的原型進行考察,可接觸到很多有趣的問題。關於圖像的問題,可以參考上述Soper教授的論文。有幾身像顯示出印度著名像的形象,這裏只打算留意其餘的有很強和闐影響的像。同樣,相對於尊像衣紋的線條與犍陀羅藝術有很深聯繫(寶石和裝飾部分可辨出是印度或犍陀羅的影響)的其他部分,如新德里國立博物館收藏的斷片中,有繼承北魏風格的飛天,也有採納早期中國佛教美術的表現方式。Soper教授也注意到這一點,“這些諸像沒有試圖表現印度式繪法,而是有意對實物進行忠實的記錄”(參照《敦煌瑞像圖》352頁)。注意諸像優美的輪廓線,可發現連貫精致的勾勒線幾乎沒有大的晃動。A塊最初三身像的華蓋,實際可與敦煌初唐時期窟中殘留的支撐肋材末端翻翹成拱形的華蓋做比較。那些華蓋邊緣挂小的吊鍾形裝飾,稍加暈染和高光的同時,下方添加了舌狀的描繪。更晚期的敦煌畫中,這種“吊鍾形裝飾”變得很長,平行的色線成穗形。體現此畫8世紀作品的風格特色,其他還可舉出諸尊臉部的描繪。特別是嘴部,可與《樹下說法圖》(參照第1卷圖7)的諸像做比較。另外蓮華座的蓮瓣表現得非常結實,時而還加入紅色葉脈的華麗裝飾,可窺出此畫是早期的範例。綜上所述,此作品儘管殘損極其嚴重,但對於曾經存在于敦煌第220窟的同趣的繪畫、保存於大乘佛教指導中心和闐以及佛教發祥地印度等地現在已經遺失的佛畫來說,這畫能使人窺到很多東西,从這一點上它是非常重要的遺物。

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)