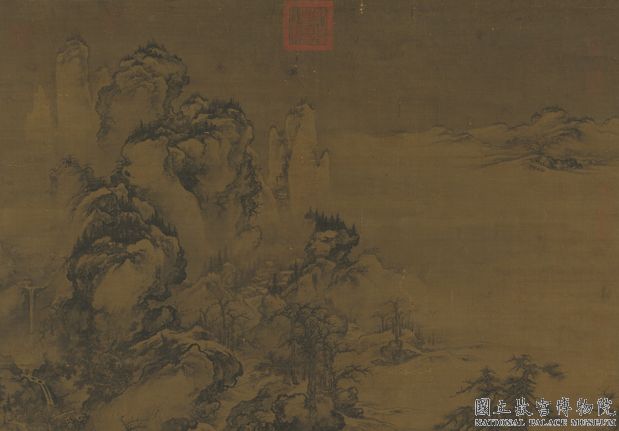

Period:Tang dynasty Production date:800-850

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha landscape musician dancer architecture paradise 佛 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) 供養人 (Chinese) 樂獅 (Chinese) 舞伎 (Chinese) 建築 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 185.50 centimetres (Textile in frame) Height: 168 centimetres Width: 139.50 centimetres (Textile in frame) Width: 121.60 centimetres Depth: 3.80 centimetres (Textile in frame with wall fixing) Depth: 3.30 centimetres (Textile in frame)

Description:

Large painting showing the Paradise of Śākyamuni in a Chinese architectural setting. The composition is simple and uncluttered, with the principal figures standing prominently against the background. Śākyamuni is seated on the top level. Below him are musicians and dancers, and further below is seated the Cosmological Buddha, Vairocana. At the bottom are female and male donor figures. The figures are symmetrically arranged in tiers in an architectural framework. The side scenes illustrate the story of Prince Sujati as told in the ‘Baoen jing’ (‘Sutra of requiting blessings received’), one of the many jātaka stories which recounts events in Śākyamuni’s previous incarnations. The painting has a textile border and along the topmost edge would have been loops through which a pole would have been passed for hanging. Made of ink and colours on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00034148_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00100738_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00507156_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00763936_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_1.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_2.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_3.jpg)

![图片[9]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_4.jpg)

![图片[10]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_5.jpg)

![图片[11]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_6.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:Like Pl.8, this scene depicts the paradise of Sākyamuni with side scenes illustrating the story of Prince Sujāti. Sākyamuni, both hands in vitarka-,or preaching, mudrā, is seated between two Bodhisattvas above a dancer on a platform between two groups of musicians. Below them is the familiar lotus lake with golden islands on which stand a jiva-jiva——or bird with two human heads——on the left, and a kalavinka——with one head——on the right (Fig.38). These occupy only a limited space on either side, and the main part of the foreground is devoted to a second triad with a central Buddha, accompanied by a Bodhisattva and a monk. This Buddha has on his robe various cosmological emblems (Pl.11-3): the sun and moon on either shoulder, Mt. Sumeru on the breast, and to either side of that the figures of a four-armed god and of an ascetic seated on a tripod. Although Eiichi Matsumoto proposed that this Buddha should be identified as Vairocana, it is also possible that he represents Sākyamuni in his cosmic aspect. If so, this would illustrate the main thesis of the Lotus Sutra, in the course of preaching which the Buddha revealed that the master who appeared as Sākyamuni was in fact merely a corporeal manifestation of the eternal Buddha on earth and the embodiment of cosmic truth (cf:Ch’en, 1964, p.380).The narrative of the side scenes, taken from the Baoen-sutra, begins at the top of the right margin (Fig.35). with successive scenes following one another and continuing upwards from the bottom of the left margin (Fig.34).The first scene shows the tutelary spirit of the palace appearing to give warning to the impending treachery of the minister Rahula, in revolt against his ruler. A ladder shows the escape of the king, his wife, and little son, Sujāti. At first they have a bag of provisions for their flight, but when these are exhausted Sujāti has to intervene and offer his own flesh to save his mother from being killed for food by the king. On the left, in the third scene, the parents take two of the last three pieces of flesh from Sujati and leave him to continue on their journey alone (Pl.11-4).When they have done so,Sujati gives his last piece of flesh to some wild animals, here represented by a white lion, who finally changes into his true shape as Sakra Devendra (the god Indra) and restores Sujāti to wholeness.In style, several features of this painting appear to point to a date in the first half of the ninth century. The composition, although more elaborate than that of Pl.7 which we have seen to be related to early Tang preaching scenes in the wall paintings at Dunhuang, is still far from being as elaborate as those of the later Tang paradise scenes. In particular the architectural setting behind the main Buddha is confined to a single large pavilion, with a verandah just visible on either side. The three principal figures are left free and prominent, to the extent that the two monk figures between them are seen at a lower level, head and shoulders only. This still recalls, although by different means, the prominence given to the Buddha in the embroidery of Sākyamuni Preaching on the Vulture Peak (Vol.3,Pl.1), where the two monks stand behind the Bodhisattvas to leave the Buddha completely free. This uncluttered arrangement means that in front of the platform with the dancer and musicians there is room for the second group with a central Buddha, accompanied by a Bodhisattva and monk.In the actual delineation of the figures, the robes hang in smooth and easy curves, undisturbed by sudden twists or turns. The haloes of the various Bodhisattvas and musicians, indeed that of the lower Buddha as well, are chiefly composed of patterns derived from lotus petals and executed in broad outlines. The harder, more geometric lines of later halo patterns can be contrasted to this. Similarly, the facial features and hands, particularly those of the principal figures, are executed with delicacy and subtlety, as well as with care. It is possible to compare a detail such as the face of one of the Bodhisattvas, with a similar face from a later painting (Stein painting 41, dated A.D.939, Vol.2, Pl. 17) in order to appreciate this. In general, the features are contained within the facial outline, although where a figure is in three-quarter view, the line of the upper eyelid may often project beyond the outline. This happens more often, if not invariably, in the paintings of the tenth century.The landscapes of the narrative to either side follow a pattern familiar from the cave paintings as well .In general, the scenes seem to be linked in pairs, with a major element, usually a cliff or summit, appearing above the upper scene. Although the technique looks simple, with bands of red and green colour alternating and accented by ink to mark the folds and contours, it is used to advantage. There is often a triangular wedge or repoussoir to create a flat space for the episode, a longer slope set diagonally and returning to separate a pair of scenes, and a group of rocks with a predominantly vertical stance to close with a high horizon before the sequence begins again with a foreground scene on a flat setting. These vertical elements generally incorporate an overhanging cliff. Those at the very top on either side form peaks which are easily read as being larger or more distant, although in fact the trees that grow on them differ not at all from those lower down, The trunks of these trees are set well below the horizon line, while the foliage is silhouetted beyond it. The one building shown here is set at a diagonal, but the wall indicating the capital city of the country of Vārānasī runs straight across. Cartouches for the scenes, coloured red or yellow, alternate on the margins, with the topmost one centrally placed. Unlike in Pl.8, none of the cartouches is actually inscribed, probably because the story would be instantly recognizable and its episodes readily followed from the depiction. The large panel between the two groups of donor figures below (Fig.72) is similarly left blank, and we are left to conjecture whether such a painting was simply held in readiness for a commission, or whether the donor figures had become an essential part of the whole, not to be omitted even when there was no specific donor. Their demure attitudes, kneeling with joined hands, and the broad and slightly limp cap ribbons of the men serve to confirm that this painting dates from shortly before the middle of the ninth century; the donors of Fig.73(dated A.D.864)are a close comparison. Rawson 1992:No Buddhist paintings by major atists of the Tang dynasty have survived, as the proscription of foreign religions in China between 842 and 845 resulted in the widespread destruction of Buddhist monuments and works of art. What has survived from the Tang period is an important collection of Buddhist paintings on silk and paper found by Aurel Stein in cave 17 in the Valley of the Thousand Buddhas, near the oasis town of Dunhuang at the Chinese end of the Silk Route. Since Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation between 781 and 847, its cave shrines and paintings escaped destruction. The paintings from cave 17 represent a wide range of devotional art by anonymous artisans, showing a mixture of Chinese, Tibetan, Khotanese and Central Asian influences. These paintings, dating from the eight to the tenth century, were stored together with many thousands of manuscripts in bundles in the former memorial chapel of the monk Hong Bian (d. c. 862), a cave walled up in the tenth century. The paintings from cave 17 represent gifts from individuals for use in monasteries, perhaps for display when prayers were said for a particular deceased relative. The paradise paintings are among the largest and most important from cave 17. The uncluttered composition is in contrast to the more complex compositions of the 10th century. Shown in landscape settings, the scenes provide rare instances of landscape in the corpus of Dunhuang paintings; such settings for religious stories were to make an important contribution to China’s long tradition of landscape painting. Details of Stein’s site-mark numbering system (Serindia, p. xv, fn 16)”Some notes concerning the arrangement of entries in the Descriptive Lists may usefully find brief record here. The arrangement follows throughout the numerical order of the ‘site-marks’. As these had to be given as the objects were discovered, acquired, or unpacked, this numerical order does not anywhere represent an attempt at systematic classification. ‘Site-marks’ given at the time of discovery show the initial letter of the site, the number of the ruin, etc., followed by plain Arabic figures, e.g. N.XXIV.xiii.35. In such cases these last figures correspond to the actual sequence of ‘finds’. When ‘site-mark’ numbers were given by myself at the site, but after the day’s work, they are preceded by a zero, e.g. L.A.VI.ii.061. When objects had been marked by me merely with the place of discovery and numbers were subsequently added at the time of unpacking at the British Museum, two zeros precede the numbers, e.g. M.I.ix.003.Where it has been found convenient to indicate in the descriptive entry for one particular object descriptive details equally applicable to other objects of a closely related type, an asterisk has been prefixed to the ‘site-mark’, e.g. *Ch.0010.In a few cases where partially effaced ‘site-marks’ had been misread at the British Museum, the necessary corrections were subsequently effected by me in the light of my diary records when dealing with the remains of the particular site. In all cases the ‘site-mark’ in the Descriptive List is to be considered as the one finally verified.Throughout the abbreviations R. and L. have been used to indicate the right and left side of objects as they are seen in reproductions, except where the right and left proper of the body are referred to.” The Getty’s curatorial team suggests the title as Requiting Kindness Sutra Paradise

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha landscape musician dancer architecture paradise 佛 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) 供養人 (Chinese) 樂獅 (Chinese) 舞伎 (Chinese) 建築 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 185.50 centimetres (Textile in frame) Height: 168 centimetres Width: 139.50 centimetres (Textile in frame) Width: 121.60 centimetres Depth: 3.80 centimetres (Textile in frame with wall fixing) Depth: 3.30 centimetres (Textile in frame)

Description:

Large painting showing the Paradise of Śākyamuni in a Chinese architectural setting. The composition is simple and uncluttered, with the principal figures standing prominently against the background. Śākyamuni is seated on the top level. Below him are musicians and dancers, and further below is seated the Cosmological Buddha, Vairocana. At the bottom are female and male donor figures. The figures are symmetrically arranged in tiers in an architectural framework. The side scenes illustrate the story of Prince Sujati as told in the ‘Baoen jing’ (‘Sutra of requiting blessings received’), one of the many jātaka stories which recounts events in Śākyamuni’s previous incarnations. The painting has a textile border and along the topmost edge would have been loops through which a pole would have been passed for hanging. Made of ink and colours on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00034148_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00100738_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00507156_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00763936_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_1.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_2.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_3.jpg)

![图片[9]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_4.jpg)

![图片[10]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_5.jpg)

![图片[11]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC2811_6.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:Like Pl.8, this scene depicts the paradise of Sākyamuni with side scenes illustrating the story of Prince Sujāti. Sākyamuni, both hands in vitarka-,or preaching, mudrā, is seated between two Bodhisattvas above a dancer on a platform between two groups of musicians. Below them is the familiar lotus lake with golden islands on which stand a jiva-jiva——or bird with two human heads——on the left, and a kalavinka——with one head——on the right (Fig.38). These occupy only a limited space on either side, and the main part of the foreground is devoted to a second triad with a central Buddha, accompanied by a Bodhisattva and a monk. This Buddha has on his robe various cosmological emblems (Pl.11-3): the sun and moon on either shoulder, Mt. Sumeru on the breast, and to either side of that the figures of a four-armed god and of an ascetic seated on a tripod. Although Eiichi Matsumoto proposed that this Buddha should be identified as Vairocana, it is also possible that he represents Sākyamuni in his cosmic aspect. If so, this would illustrate the main thesis of the Lotus Sutra, in the course of preaching which the Buddha revealed that the master who appeared as Sākyamuni was in fact merely a corporeal manifestation of the eternal Buddha on earth and the embodiment of cosmic truth (cf:Ch’en, 1964, p.380).The narrative of the side scenes, taken from the Baoen-sutra, begins at the top of the right margin (Fig.35). with successive scenes following one another and continuing upwards from the bottom of the left margin (Fig.34).The first scene shows the tutelary spirit of the palace appearing to give warning to the impending treachery of the minister Rahula, in revolt against his ruler. A ladder shows the escape of the king, his wife, and little son, Sujāti. At first they have a bag of provisions for their flight, but when these are exhausted Sujāti has to intervene and offer his own flesh to save his mother from being killed for food by the king. On the left, in the third scene, the parents take two of the last three pieces of flesh from Sujati and leave him to continue on their journey alone (Pl.11-4).When they have done so,Sujati gives his last piece of flesh to some wild animals, here represented by a white lion, who finally changes into his true shape as Sakra Devendra (the god Indra) and restores Sujāti to wholeness.In style, several features of this painting appear to point to a date in the first half of the ninth century. The composition, although more elaborate than that of Pl.7 which we have seen to be related to early Tang preaching scenes in the wall paintings at Dunhuang, is still far from being as elaborate as those of the later Tang paradise scenes. In particular the architectural setting behind the main Buddha is confined to a single large pavilion, with a verandah just visible on either side. The three principal figures are left free and prominent, to the extent that the two monk figures between them are seen at a lower level, head and shoulders only. This still recalls, although by different means, the prominence given to the Buddha in the embroidery of Sākyamuni Preaching on the Vulture Peak (Vol.3,Pl.1), where the two monks stand behind the Bodhisattvas to leave the Buddha completely free. This uncluttered arrangement means that in front of the platform with the dancer and musicians there is room for the second group with a central Buddha, accompanied by a Bodhisattva and monk.In the actual delineation of the figures, the robes hang in smooth and easy curves, undisturbed by sudden twists or turns. The haloes of the various Bodhisattvas and musicians, indeed that of the lower Buddha as well, are chiefly composed of patterns derived from lotus petals and executed in broad outlines. The harder, more geometric lines of later halo patterns can be contrasted to this. Similarly, the facial features and hands, particularly those of the principal figures, are executed with delicacy and subtlety, as well as with care. It is possible to compare a detail such as the face of one of the Bodhisattvas, with a similar face from a later painting (Stein painting 41, dated A.D.939, Vol.2, Pl. 17) in order to appreciate this. In general, the features are contained within the facial outline, although where a figure is in three-quarter view, the line of the upper eyelid may often project beyond the outline. This happens more often, if not invariably, in the paintings of the tenth century.The landscapes of the narrative to either side follow a pattern familiar from the cave paintings as well .In general, the scenes seem to be linked in pairs, with a major element, usually a cliff or summit, appearing above the upper scene. Although the technique looks simple, with bands of red and green colour alternating and accented by ink to mark the folds and contours, it is used to advantage. There is often a triangular wedge or repoussoir to create a flat space for the episode, a longer slope set diagonally and returning to separate a pair of scenes, and a group of rocks with a predominantly vertical stance to close with a high horizon before the sequence begins again with a foreground scene on a flat setting. These vertical elements generally incorporate an overhanging cliff. Those at the very top on either side form peaks which are easily read as being larger or more distant, although in fact the trees that grow on them differ not at all from those lower down, The trunks of these trees are set well below the horizon line, while the foliage is silhouetted beyond it. The one building shown here is set at a diagonal, but the wall indicating the capital city of the country of Vārānasī runs straight across. Cartouches for the scenes, coloured red or yellow, alternate on the margins, with the topmost one centrally placed. Unlike in Pl.8, none of the cartouches is actually inscribed, probably because the story would be instantly recognizable and its episodes readily followed from the depiction. The large panel between the two groups of donor figures below (Fig.72) is similarly left blank, and we are left to conjecture whether such a painting was simply held in readiness for a commission, or whether the donor figures had become an essential part of the whole, not to be omitted even when there was no specific donor. Their demure attitudes, kneeling with joined hands, and the broad and slightly limp cap ribbons of the men serve to confirm that this painting dates from shortly before the middle of the ninth century; the donors of Fig.73(dated A.D.864)are a close comparison. Rawson 1992:No Buddhist paintings by major atists of the Tang dynasty have survived, as the proscription of foreign religions in China between 842 and 845 resulted in the widespread destruction of Buddhist monuments and works of art. What has survived from the Tang period is an important collection of Buddhist paintings on silk and paper found by Aurel Stein in cave 17 in the Valley of the Thousand Buddhas, near the oasis town of Dunhuang at the Chinese end of the Silk Route. Since Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation between 781 and 847, its cave shrines and paintings escaped destruction. The paintings from cave 17 represent a wide range of devotional art by anonymous artisans, showing a mixture of Chinese, Tibetan, Khotanese and Central Asian influences. These paintings, dating from the eight to the tenth century, were stored together with many thousands of manuscripts in bundles in the former memorial chapel of the monk Hong Bian (d. c. 862), a cave walled up in the tenth century. The paintings from cave 17 represent gifts from individuals for use in monasteries, perhaps for display when prayers were said for a particular deceased relative. The paradise paintings are among the largest and most important from cave 17. The uncluttered composition is in contrast to the more complex compositions of the 10th century. Shown in landscape settings, the scenes provide rare instances of landscape in the corpus of Dunhuang paintings; such settings for religious stories were to make an important contribution to China’s long tradition of landscape painting. Details of Stein’s site-mark numbering system (Serindia, p. xv, fn 16)”Some notes concerning the arrangement of entries in the Descriptive Lists may usefully find brief record here. The arrangement follows throughout the numerical order of the ‘site-marks’. As these had to be given as the objects were discovered, acquired, or unpacked, this numerical order does not anywhere represent an attempt at systematic classification. ‘Site-marks’ given at the time of discovery show the initial letter of the site, the number of the ruin, etc., followed by plain Arabic figures, e.g. N.XXIV.xiii.35. In such cases these last figures correspond to the actual sequence of ‘finds’. When ‘site-mark’ numbers were given by myself at the site, but after the day’s work, they are preceded by a zero, e.g. L.A.VI.ii.061. When objects had been marked by me merely with the place of discovery and numbers were subsequently added at the time of unpacking at the British Museum, two zeros precede the numbers, e.g. M.I.ix.003.Where it has been found convenient to indicate in the descriptive entry for one particular object descriptive details equally applicable to other objects of a closely related type, an asterisk has been prefixed to the ‘site-mark’, e.g. *Ch.0010.In a few cases where partially effaced ‘site-marks’ had been misread at the British Museum, the necessary corrections were subsequently effected by me in the light of my diary records when dealing with the remains of the particular site. In all cases the ‘site-mark’ in the Descriptive List is to be considered as the one finally verified.Throughout the abbreviations R. and L. have been used to indicate the right and left side of objects as they are seen in reproductions, except where the right and left proper of the body are referred to.” The Getty’s curatorial team suggests the title as Requiting Kindness Sutra Paradise

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)