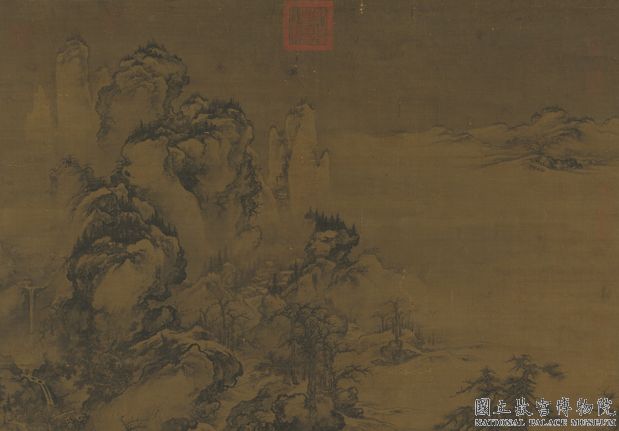

Period:Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Production date:926-975 (circa)

Materials:paper, 紙 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:bodhisattva 菩薩 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) 國王/王后 (Chinese) king/queen attendant

Dimensions:Height: 73.20 centimetres Width: 30.70 centimetres

Description:

Painting showing the famous story of Mañjuśrī, Bodhisattva of Wisdom, visiting Vimalakirti on his sickbed. Vimalakirti, a rich Indian layman, is not shown here (this was probably the right-hand illustration of a pair; he would have appeared in the left-hand one). Mañjuśrī is seated on a lion-throne, a bodhisattva in front of him pouring an inexhaustible supply of rice for the faithful. Below are Chinese kings and attendants. Ink and colour on paper.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637_1.jpg)

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637_1.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1983:The story of the visit of the Bodhisattva Manjusri to Vimalakirti on his sick-bed was immensely popular in China. Vimalakirti was a rich Indian layman, skilled at argument and with a profound knowledge of the Buddha’s teachings. When the Buddha asked his disciples to go and enquire after Vimalakirti’s health, they refused one after another, recalling previous occasions when he had outwitted them. Finally Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom agreed to go, and a great concourse assembled to hear their discussion, which covered subjects such as the nature of non-duality, and the illness of a Bodhisattva. The debate ends with Manjusri expressing his unqualified admiration for the depth of Vimalakirti’s knowledge. The Vimalakirti-sutra is one of the most important in Mahayana Buddhism; Chinese scholars, introduced to it through the excellent translation made by Kumarajiva (died A.D. 413), appreciated Vimalskirti’s intellectual qualities, and no doubt his wit also; when the disciple Sariputra entered the assembly and found no seat, Vimalakirti read his thoughts, and asked if he had come to hear the Law, or to look for seats. In this painting only Manjusri is seen; Vimalakirti would have been shown on his bed, holding a fan, in a matching composition on the left. A ruler in a splendid robe with dragons and the sun and moon motifs, one of those who had come to hear the discussion, is seen in the foreground (Pl. 53-4). Instead of Manjusri’s usual mount, the lion, a number of small lions are shown in the openings beneath the dais on which he is seated (Pl. 53-3).The subject has already been seen in a silk painting of the late eighth century (Vol. 1, Pl. 20), which, though much damaged, still shows the subject in considerable detail, with a number of the miracles wrought by Vimalakirti appearing above the scene of the actual debate.A measure of simplification is seen in a series of ink sketches of the subject on separate sheets of paper, afterwards pasted together (Figs. 86-88). The scenes shown include the city of Vaisali; Manjusri and part of the assembly (Fig. 86b); and, on the reverse side (Fig. 86a), Vimalakirti on his covered sick-bed, with monks and Bodhisattvas (one group seated on a cloud, one pouring rice from a bowl, see below). These scenes and the text of a letter (translated by Waley, 1931, pp.315-16) are on two of the sheets. The third sheet has only a few figures on one side, and several of the meditations of Queen Vaidehi on the other; it is pasted upside-down in relation to the first two sheets. Like another series of ink sketches on paper, of scenes from a paradise of Maitreya (Fig. 85, British Library, S. 259), these may have been copied from a wall painting.Although on paper, this painting has the character of a finished work. The iconography is still further simplified and even altered to suit not only the smaller format but the requirements of a later time. Through this process Manjusri has become the dominant figure, almost as if the painting were devoted to him alone, with a retinue of much smaller figures of Bodhisattvas, monks, guardian kings and a Dharmapala behind him. In the foreground, the king or ruler, with an even more numerous group of attendants, is also very prominent; this is in keeping with the more sumptuous portrayal of donor figures in the Five Dynasties and early Song dynasty. Nothing is left of the setting to the debate, and of the other narrative scenes seen in the silk painting there are only two. The first shows a Bodhisattva pouring rice out of a bowl, to demonstrate, as Waley put it, its inexhaustibility: “one of the auditors thought ‘This rice is little and all the persons of the great assembly must eat’. The Dhyani Bodhisattva replied: ‘Sooner shall the four seas be empty than this rice fail’.” The second scene is smaller still, just under the canopy, and shows three small boys playing musical instruments (Pl. 53-2). Possibly this charming group is an adaptation of the episode when the sons of elders of the city of Vaisali offered precious canopies to Sakyamuni.In style and composition, this painting is closely related to the painting of Avalokitesvara (Pl.52), with an almost identical canopy and figures supported in similar fashion on small clouds. There is also a similarity in size between the main figures of Avalokitesvara and Manjusri, and in the prominence of the single donor figure in Pl.52, who like the ruler in this painting is shown within the main picture area rather than outside it. Although the costume and headdress of Manjusri still follow ninth century prototypes, the manner of their depiction, such as the flattening of drapery folds or the summary execution of facial features, indicates that this painting dates from the tenth century. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1983:文殊菩薩訪問病床上的維摩居士的故事,在中國廣爲人知。維摩是印度富裕的居士,有辯才,對佛教有很深的造詣。佛陀委託弟子們去探望病中的維摩時,弟子們想起曾被維摩的辯論擊敗,紛紛辭退。結果,作爲智慧菩薩的文殊同意去探望,聚集了衆多聽他們答辯的人群。答辯涉及到了不二法門以及菩薩的疾病,故事以文殊從心底讚歎維摩的淵博知識而結束。《維摩經》是大乘佛教最重要的經典之一。中國的佛教學者們是通過鳩摩羅什(死於413年)的優秀的漢譯本,充分瞭解到有關維摩的聰明資質和機智的。如,佛弟子舍利弗到了集結地,看已經滿座,怎麽也找不到空座,維摩看出他的意思,就問是來聽法呢?還是爲了來找座?本圖僅見文殊菩薩,可能與其相對的左幅位置,描繪著維摩手持扇子,橫臥床上的姿容。此圖的前景中有前來聽講的國王,國王身著龍和日月文樣的華麗禮服(參照圖53-4)。文殊通常是乘獅子,但在這裏卻坐在方形台座上,台座上繪著很多小獅子作爲替代(參照圖53-3)。此主題的繪畫曾在8世紀末的絹畫(參照第1卷圖20)中見過,那絹畫雖然殘損嚴重,但對細部的描繪都很詳細,答辯場面上方繪有因維摩的辯論出現的幾處奇迹。另外,還有簡單墨描的《維摩經變相圖》(參照Fig.86~88)。它現在的形式是後來用幾張草圖粘合成的。正面(參照Fig.86-b)有毘耶離城的場景和文殊菩薩及聽衆的一部分;背面(參照Fig.86-a)是圍著病榻上的維摩的菩薩和比丘等(繪有乘雲的一群菩薩,手持缽中的香飯要溢出的樣子,見下)。這些場景和書寫的經文(參照Waley《敦煌畫目錄》,315~316頁)佔據了兩紙,另一紙的正面有數人,背面描著韋提希夫人十六想觀的數個場景。第三紙粘在前兩紙上。同樣的墨描作品,還有《彌勒下生經變白描粉本》(參照Fig.85),這些可能都是壁畫的模寫。本圖的作品雖然是繪在紙上,但是完整的畫作。圖像方面,不僅合乎小型畫面,也應了時代的需要,有很大的簡化和變更。整個畫面似乎只供奉文殊菩薩一人,把他畫得很大。菩薩、比丘、天王,以及其背後的護法神等文殊的眷屬被畫得很小。前景中的國王也比衆多隨從繪得稍大,很突出。從五代一直到北宋時期的供養畫中,都可見到相關的配有華麗衣裳的肖像式的供養人。畫面中未見一個表現辯論的場景,絹畫中所見的故事場景也只見到兩處,一是從菩薩所持的缽中有香飯溢出的樣子,Waley指出這是描寫無盡藏,化菩薩回答說:如果想食盡這香飯比喝盡四海還困難”。另一處是在華蓋的正下方,有在雲端上奏樂的三個童子(參照圖53-2)。這可愛的群體,是毘耶離城的長者子向釋迦牟尼奉獻昂貴的華蓋故事的翻版。風格和圖像方面,可看出此圖與前面的《水月觀音圖》(圖52)有非常密切關係,華蓋形狀、乘著小雲的圖像風格也大致相同。另外,此文殊菩薩的尺寸與上圖的觀音大致相同。上一圖中只有一個供養人,並且佔據著圖的主要位置,這和本圖前景的國王一樣,是爲了突出他的重要性。文殊菩薩的衣裳以及髮型沿襲了9世紀的原型,但描繪中也見到像衣褶的表現非常單調呆板,容貌也有簡筆畫的風格等10世紀作品的特徵。 Rawson 1992:This tenth-century Buddhist painting on silk from Dunhuang, on the Silk Route, shows the sort of official costume worn by dignitaries in the Tang dynasty. The long, flowing sleeves of the robes feature embroidered auspicious symbols, some of which may be dragons. ‘Dragon robes’, that is, robes embroidered with large dragons and other auspicious symbols, were already in use by the Tang dynasty emperors and were referred to in the “Old Tang History” (“Jiu Tang Shu”).

Materials:paper, 紙 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:bodhisattva 菩薩 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) 國王/王后 (Chinese) king/queen attendant

Dimensions:Height: 73.20 centimetres Width: 30.70 centimetres

Description:

Painting showing the famous story of Mañjuśrī, Bodhisattva of Wisdom, visiting Vimalakirti on his sickbed. Vimalakirti, a rich Indian layman, is not shown here (this was probably the right-hand illustration of a pair; he would have appeared in the left-hand one). Mañjuśrī is seated on a lion-throne, a bodhisattva in front of him pouring an inexhaustible supply of rice for the faithful. Below are Chinese kings and attendants. Ink and colour on paper.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637_1.jpg)

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.31.+-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms/Paintings/mid_RFC637_1.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1983:The story of the visit of the Bodhisattva Manjusri to Vimalakirti on his sick-bed was immensely popular in China. Vimalakirti was a rich Indian layman, skilled at argument and with a profound knowledge of the Buddha’s teachings. When the Buddha asked his disciples to go and enquire after Vimalakirti’s health, they refused one after another, recalling previous occasions when he had outwitted them. Finally Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom agreed to go, and a great concourse assembled to hear their discussion, which covered subjects such as the nature of non-duality, and the illness of a Bodhisattva. The debate ends with Manjusri expressing his unqualified admiration for the depth of Vimalakirti’s knowledge. The Vimalakirti-sutra is one of the most important in Mahayana Buddhism; Chinese scholars, introduced to it through the excellent translation made by Kumarajiva (died A.D. 413), appreciated Vimalskirti’s intellectual qualities, and no doubt his wit also; when the disciple Sariputra entered the assembly and found no seat, Vimalakirti read his thoughts, and asked if he had come to hear the Law, or to look for seats. In this painting only Manjusri is seen; Vimalakirti would have been shown on his bed, holding a fan, in a matching composition on the left. A ruler in a splendid robe with dragons and the sun and moon motifs, one of those who had come to hear the discussion, is seen in the foreground (Pl. 53-4). Instead of Manjusri’s usual mount, the lion, a number of small lions are shown in the openings beneath the dais on which he is seated (Pl. 53-3).The subject has already been seen in a silk painting of the late eighth century (Vol. 1, Pl. 20), which, though much damaged, still shows the subject in considerable detail, with a number of the miracles wrought by Vimalakirti appearing above the scene of the actual debate.A measure of simplification is seen in a series of ink sketches of the subject on separate sheets of paper, afterwards pasted together (Figs. 86-88). The scenes shown include the city of Vaisali; Manjusri and part of the assembly (Fig. 86b); and, on the reverse side (Fig. 86a), Vimalakirti on his covered sick-bed, with monks and Bodhisattvas (one group seated on a cloud, one pouring rice from a bowl, see below). These scenes and the text of a letter (translated by Waley, 1931, pp.315-16) are on two of the sheets. The third sheet has only a few figures on one side, and several of the meditations of Queen Vaidehi on the other; it is pasted upside-down in relation to the first two sheets. Like another series of ink sketches on paper, of scenes from a paradise of Maitreya (Fig. 85, British Library, S. 259), these may have been copied from a wall painting.Although on paper, this painting has the character of a finished work. The iconography is still further simplified and even altered to suit not only the smaller format but the requirements of a later time. Through this process Manjusri has become the dominant figure, almost as if the painting were devoted to him alone, with a retinue of much smaller figures of Bodhisattvas, monks, guardian kings and a Dharmapala behind him. In the foreground, the king or ruler, with an even more numerous group of attendants, is also very prominent; this is in keeping with the more sumptuous portrayal of donor figures in the Five Dynasties and early Song dynasty. Nothing is left of the setting to the debate, and of the other narrative scenes seen in the silk painting there are only two. The first shows a Bodhisattva pouring rice out of a bowl, to demonstrate, as Waley put it, its inexhaustibility: “one of the auditors thought ‘This rice is little and all the persons of the great assembly must eat’. The Dhyani Bodhisattva replied: ‘Sooner shall the four seas be empty than this rice fail’.” The second scene is smaller still, just under the canopy, and shows three small boys playing musical instruments (Pl. 53-2). Possibly this charming group is an adaptation of the episode when the sons of elders of the city of Vaisali offered precious canopies to Sakyamuni.In style and composition, this painting is closely related to the painting of Avalokitesvara (Pl.52), with an almost identical canopy and figures supported in similar fashion on small clouds. There is also a similarity in size between the main figures of Avalokitesvara and Manjusri, and in the prominence of the single donor figure in Pl.52, who like the ruler in this painting is shown within the main picture area rather than outside it. Although the costume and headdress of Manjusri still follow ninth century prototypes, the manner of their depiction, such as the flattening of drapery folds or the summary execution of facial features, indicates that this painting dates from the tenth century. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1983:文殊菩薩訪問病床上的維摩居士的故事,在中國廣爲人知。維摩是印度富裕的居士,有辯才,對佛教有很深的造詣。佛陀委託弟子們去探望病中的維摩時,弟子們想起曾被維摩的辯論擊敗,紛紛辭退。結果,作爲智慧菩薩的文殊同意去探望,聚集了衆多聽他們答辯的人群。答辯涉及到了不二法門以及菩薩的疾病,故事以文殊從心底讚歎維摩的淵博知識而結束。《維摩經》是大乘佛教最重要的經典之一。中國的佛教學者們是通過鳩摩羅什(死於413年)的優秀的漢譯本,充分瞭解到有關維摩的聰明資質和機智的。如,佛弟子舍利弗到了集結地,看已經滿座,怎麽也找不到空座,維摩看出他的意思,就問是來聽法呢?還是爲了來找座?本圖僅見文殊菩薩,可能與其相對的左幅位置,描繪著維摩手持扇子,橫臥床上的姿容。此圖的前景中有前來聽講的國王,國王身著龍和日月文樣的華麗禮服(參照圖53-4)。文殊通常是乘獅子,但在這裏卻坐在方形台座上,台座上繪著很多小獅子作爲替代(參照圖53-3)。此主題的繪畫曾在8世紀末的絹畫(參照第1卷圖20)中見過,那絹畫雖然殘損嚴重,但對細部的描繪都很詳細,答辯場面上方繪有因維摩的辯論出現的幾處奇迹。另外,還有簡單墨描的《維摩經變相圖》(參照Fig.86~88)。它現在的形式是後來用幾張草圖粘合成的。正面(參照Fig.86-b)有毘耶離城的場景和文殊菩薩及聽衆的一部分;背面(參照Fig.86-a)是圍著病榻上的維摩的菩薩和比丘等(繪有乘雲的一群菩薩,手持缽中的香飯要溢出的樣子,見下)。這些場景和書寫的經文(參照Waley《敦煌畫目錄》,315~316頁)佔據了兩紙,另一紙的正面有數人,背面描著韋提希夫人十六想觀的數個場景。第三紙粘在前兩紙上。同樣的墨描作品,還有《彌勒下生經變白描粉本》(參照Fig.85),這些可能都是壁畫的模寫。本圖的作品雖然是繪在紙上,但是完整的畫作。圖像方面,不僅合乎小型畫面,也應了時代的需要,有很大的簡化和變更。整個畫面似乎只供奉文殊菩薩一人,把他畫得很大。菩薩、比丘、天王,以及其背後的護法神等文殊的眷屬被畫得很小。前景中的國王也比衆多隨從繪得稍大,很突出。從五代一直到北宋時期的供養畫中,都可見到相關的配有華麗衣裳的肖像式的供養人。畫面中未見一個表現辯論的場景,絹畫中所見的故事場景也只見到兩處,一是從菩薩所持的缽中有香飯溢出的樣子,Waley指出這是描寫無盡藏,化菩薩回答說:如果想食盡這香飯比喝盡四海還困難”。另一處是在華蓋的正下方,有在雲端上奏樂的三個童子(參照圖53-2)。這可愛的群體,是毘耶離城的長者子向釋迦牟尼奉獻昂貴的華蓋故事的翻版。風格和圖像方面,可看出此圖與前面的《水月觀音圖》(圖52)有非常密切關係,華蓋形狀、乘著小雲的圖像風格也大致相同。另外,此文殊菩薩的尺寸與上圖的觀音大致相同。上一圖中只有一個供養人,並且佔據著圖的主要位置,這和本圖前景的國王一樣,是爲了突出他的重要性。文殊菩薩的衣裳以及髮型沿襲了9世紀的原型,但描繪中也見到像衣褶的表現非常單調呆板,容貌也有簡筆畫的風格等10世紀作品的特徵。 Rawson 1992:This tenth-century Buddhist painting on silk from Dunhuang, on the Silk Route, shows the sort of official costume worn by dignitaries in the Tang dynasty. The long, flowing sleeves of the robes feature embroidered auspicious symbols, some of which may be dragons. ‘Dragon robes’, that is, robes embroidered with large dragons and other auspicious symbols, were already in use by the Tang dynasty emperors and were referred to in the “Old Tang History” (“Jiu Tang Shu”).

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)