Period:Tang dynasty Production date:836

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise landscape 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) attendant

Dimensions:Height: 180 centimetres (Framed) Height: 152.30 centimetres Width: 201 centimetres (Framed) Width: 177.80 centimetres Depth: 3 centimetres (Framed)

Description:

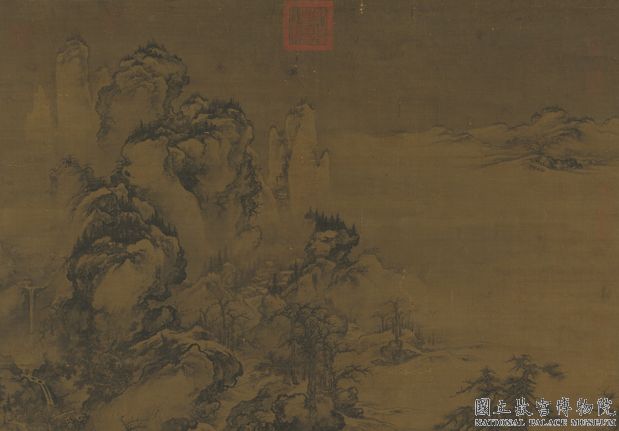

Painting of the Paradise of Bhaiṣajyaguru, Buddha of Healing, set in a landscape with Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra and attendants. Bodhisattvas beside the Buddha are painted in Tibetan style. Esoteric Buddhist figures in the lower section (partly destroyed). Tibetan and Chinese inscriptions. Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_1.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_2.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_3.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_4.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_5.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:In spite of extensive damage to the lower half, this painting is one of the largest silk paintings from Dunhuang. It is also one of the most important because the central inscription in Tibetan and Chinese, although almost completely faded when first seen, can be read and does provide a date. This inscription (see below) had not been read when Waley catalogued the Stein collection, but has recently been revealed by infra-red photography (Fig.43) and published by Heather Karmay in her book on Early Sino-Tibetan Art. Her translation of the Tibetan part reads as follows:In the year of the dragon, I, the monk dPal-dbyangs, painted in a group the images of Bhaisajyaguru; Samantabhadra; Mañjusri-kumara; a thousand-armed, thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara; Chintāmanicakra; Parina-tacakra etc., for the benefit of my health and to transfer the merit (?) (created by the act of painting, to all beings).The Chinese inscription, in nine columns from left to right, repeats the substance of the Tibetan part, but is more specific as to date. More of the text can be made out than when it was published by Karmay: 建造畢 丙辰歲九月癸卯朔十五日丁巳 □共登覺路 □□□法界蒼生同 以此功德奉爲先亡□# 空羂索一軀 千眼一軀如意輸一軀不 一鋪文殊普賢會一鋪千手 敬畫藥師如來法席Respectfully painted one group of Bhaisajyaguru on his dharma seat; Mañjusrī, Samantabhadra and their assemblies, one group; thousand-armed, thousand-eyed (Avalokitesvara), one group; Cintāmanicakra, one group; Amoghapāsa, one group; through this to acquire merit on behalf of his deceased (father and) mother…to be reborn in the Dharmadhatu …together ascend the way of enlightenment. The year bingchen, ninth moon guimao, the first fifteen (days), the day dingsi, executed and completed.This inscription is set in the very centre of the painting as it survives today, rather than below as with most of the silk paintings. Both the Chinese and the Tibetan texts agree in giving precedence to Bhaisajyaguru (Pl.16-3), who presides over the whole in the top centre, accompanied by two Bodhisattvas and a numerous retinue. For the rest, the text confirms what is already fairly clear from the painting. Below, on either side of the inscription, Samantabhadra and Mañjusrī are clearly recognizable by their vehicles (Pls.16-4,16-5),while at the bottom Avalokitesvara (Fig.46) in the centre can be seen to be accompanied on the left by one of his transformations, Cintamanicakra (Fig.45),with the missing figure on the right identified by the Chinese text as yet another form of Avalokitesvara, Amoghapāsa. The popularity of Mañjusrī and Samantabhadra in the period of Tibetan domination at Dunhuang is attested to by many wall paintings, and the great size of Avalokitesvara here demonstrates his popularity also. The painting is indeed identified as a mandala of Avalokitesvara by Waley, supported by Karmay, but I prefer the precedence which the dual inscription seems to give to Bhaisajyaguru. Perhaps this is not so much the paradise of the Medicine Buddha, however, as a composite reflecting the personal predilections of the Tibetan monk who commissioned the painting.Not only the dual inscription in Tibetan and Chinese, but the painting itself reveals its Tibetan connections, for here in the same composition we find, as Heather Karmay has pointed out,”two quite different styles that existed side by side in Dunhuang. The first, in which the main body of the painting is painted, is in Chinese style, and the second, confined to the portrayal of the Bodhisattvas on either side of Bhaisajyaguru, may be directly associated with the group of Tibetan paintings [from Dunhuang].” In fact, of course, it is not so much two different styles as the integration of two different modes of depiction that we find here, since the actual means-line and colouring-is exactly the same for both types of figure. The initial drawing is in pale ink, still quite easily discernible in details such as the eyebrows. Over this is the white of the skin colour, with slight shading in pink. Finally, outlines such as those of the eyebrows, mouth and major drapery lines are drawn again in a darker ink, or, in the case of the hands and fingers, ears and nose, in red. These represent common stylistic elements which are, I think, sufficient to show that the same artists were at work here. Where the figures differ is in their attitudes, in the configuration of their facial features, and in the clothes that they wear. The two chief Bodhisattvas above, lightly clothed in the Indian manner, are seated with one leg pendent, the body swaying to one side, the head not only inclined in the opposite direction but also lengthened on the one side and foreshortened on the other, while the hair falls in many small ringlets over the shoulders. This is in contrast to the demurely clothed figures of Manjusri and Samantabhadra below, although they also are seated with one leg pendent. They have almost symmetrical faces and long smooth locks of dark hair framing the shoulders and arms.In some ways the painting appears to be midway between a mandala and the usual type of paradise painting with an architectural setting. There is a landscape background, clearly visible in the upper left (Pl.16-7)and originally in the right corner also. This can just be seen to have extended behind the central Buddha group also, and the latter is flanked by now-faded plantain trees. The space around is sparsely filled with flowering plants, but there are dividing lines of tiles also, suggesting a rectangular platform for the main group and dividing the middle assemblies of Manjusri and Samantabhadra from the triad at the bottom. Some of the most charming details are the small figures of flying apsarasas around the canopies of these two Bodhisattvas; in addition one attendant on either side holds a staff from the top of which flies a panelled banner with streamers. These two great assemblies, like the apsarasas and the smaller groups of sixteen and eighteen seated figures above them (Fig.44), are essentially supported on clouds which issue out of the landscapes above. All are shown advancing towards the centre. The triad below is static, dominated by the geometric forms of the multiple arms of Avalokitesvara and the great white red-bordered circles of the haloes of Cintamanicakra and Amoghapasa.As explained by Karmay, the only bingchen year to fall within the period of Tibetan domination at Dunhuang corresponds to A.D.836. Among the sutra manuscripts also, those of this period which bear dates commonly lack any indication of the Chinese reign period, and are dated, as one might expect, by the cyclical combination alone. As the style, too, is manifestly of the ninth century, and the depiction of Manjusri and Samantabhadra not far removed from such a securely dated example as Pl.23, this date can be regarded as reliable and of considerable value in understanding the development of painting at this time. Chinese From Whitfield 1982:儘管下邊大半部分已缺失,但該繪畫仍屬敦煌絹繪中超大型作品之一。說其重要是因爲在中央部位有吐蕃和漢文對照的題記,因為褪色,肉眼幾乎無法看清,但仍可識讀,並提供年代。Waley編寫斯坦因收集的敦煌繪畫目錄时,尚不能解讀此題記,而近年通過紅外線拍照才達到解讀的可能(參見Fig.43)。Heather Karmay在其著作《早期中原與西藏藝術》(Early Sino-Tibetan Art)中有介紹,她将吐蕃文解讀如下:辰年,我,比丘dPal-dbyangs,繪藥師如來、普賢、文殊、千手千眼觀音、如意輪觀音、不空羂索觀音等諸像,爲了自身的健康並宣揚佛法(通過繪像普渡衆生)。漢文題記是從左到右豎寫的,共九行,內容與吐蕃文重復,年代標記更爲明確。現在,此漢文題記比Karmay發表時解讀的更爲詳細。建造畢丙辰歲九月癸卯朔十五日丁巳□共登覺路□□□法界蒼生同以此功德奉爲先亡□考空羂索一軀千眼一軀如意輪一軀不一鋪文殊普賢會一鋪千手敬畫藥師如來法席這些題記,不像其他很多繪畫那樣記在下方,而是在現存畫面大致中央的位置上,因而保存至今。漢文和吐蕃文兩方題記一致推崇的藥師如來(參見圖16-3),随帶二脅侍和衆多眷屬坐于上部中央,統轄整个畫面。其他諸像雖然在畫面上均可判別,但題記更能幫我們確認。下方題記兩側是普賢和文殊菩薩,可以從他們的坐騎很容易做出判斷(參見圖16-4,16-5)。另,下段中央是千手千眼觀音(參見Fig.46),左邊伴有觀音變身之一的如意輪觀音(參見Fig.45),右邊残缺的像,通過漢文題记可以判斷是另一觀音變身:不空羂索觀音。吐蕃時期,敦煌地區流行文殊和普賢,從石窟壁畫的諸例也可證明。這幅畫中的觀音佔據了較大的空間,也可確認觀音的流行。Waley確認此畫為觀音曼荼羅,Karmay也支持這个觀點,而我是從合璧的文字題記中藥師如來的優越地位得到確認的。其實,此畫並不是完全按藥師淨土圖的形式製成的,恐怕是按照吐蕃僧人帶有個人喜好的要求而製作的作品。不僅題記是吐蕃文和漢文合璧,繪畫表現上也有吐蕃化的成分。有關兩種形式的融合,我們也從畫面上可以看到。這一點正如Heather Karmay已經指出的,“……在敦煌,有兩種完全不同的形式共存。首先是繪畫的主要图像體現了完全中國化的形式,其次是在[敦煌]的一系列藥師的兩脅侍菩薩與吐蕃有緊密联係。”當然,實際上我們在這裏看到的,與其說兩種不同形式的共存,還不如說兩種不同圖像表現的統一。在兩種圖像中,線條和顔色均採用了完全一致的手法。比如可清楚辨认的眉的部分,用薄墨描下線;皮膚塗白色,用粉色薄薄晕染;施彩後,眉、口以及衣褶等均用濃墨描出,而手和指、耳朵等卻用紅色線。因爲兩种圖像都存在這種共同的表現方式,所以,可以充分肯定在該畫是由同一組畫家製作的。圖像表現不同的地方,體現在那些姿態上,即容貌和身上的衣裳的區別上。上邊的二脅侍菩薩著印度風格的輕衣,結半跏趺姿勢而坐。不僅身體向一邊扭,頭側向反面,頭的一側也顯得稍長,反側略短,有深度感。一方面,披在肩上的頭髮,髮梢形成小卷。這與下面同樣結半跏趺,姿勢端正的文殊和普賢的形成對比。文殊和普賢的面部幾乎是左右對稱的,頭髮長而平滑,可見多處結,從肩上懸到手腕。該畫的內容,按慣例位置應在配有建築物的淨土圖和曼荼羅之間。左上部的風景(參見圖16-7)尚殘留,當初在右上部也應繪有同樣的風景。另外,藥師三尊和眷屬背後一帶也應繪有風景,月光菩薩左邊略微残留的阔葉植物想必是那風景構圖的一部分。其周邊的空白處分佈稀疏的花草,上方藥師三尊群體所乘坐的寶台、中段文殊以及普賢菩薩群體和下段三尊群體的分界線是排列的磚。此畫有很多富有魅力的細節,尤其引人注目的有圍繞文殊和普賢華蓋上空起舞的小飛天,以及文殊和普賢各有一位随從手握帶著流蘇的幡竿。文殊、普賢兩群體上方的由十六~十八身小型坐像組成的群體(參見Fig.44),像飛天一樣,乘着雲從上方飞來,他們看似是向中央前進。下段三尊是靜止的,以千手千眼觀音的衆手構成的幾何形背光、如意輪觀音和不空羂索觀音紅色邊緣的白色圓形背光,佔據了畫面的大半部分。如同Karmay說明的那樣,吐蕃時期,敦煌與丙辰年相應的是只有公元836年。在佛經中,吐蕃時期通常不使用中國年號,而是使用干支來標識年代。風格上很明顯是9世紀的作品,文殊和普賢的表現方式與有確切紀年的彩色圖版第23圖《四觀音文殊普賢圖》無大差別。因此,判斷此作品中的紀年“丙辰”为836年是可信的。在研究吐蕃時期敦煌繪畫的发展上,它是極其重要的作品。

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise landscape 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 山水 (Chinese) 隨侍 (Chinese) attendant

Dimensions:Height: 180 centimetres (Framed) Height: 152.30 centimetres Width: 201 centimetres (Framed) Width: 177.80 centimetres Depth: 3 centimetres (Framed)

Description:

Painting of the Paradise of Bhaiṣajyaguru, Buddha of Healing, set in a landscape with Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra and attendants. Bodhisattvas beside the Buddha are painted in Tibetan style. Esoteric Buddhist figures in the lower section (partly destroyed). Tibetan and Chinese inscriptions. Ink and colour on silk.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_1.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_2.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_3.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_4.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.32-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC638_5.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:In spite of extensive damage to the lower half, this painting is one of the largest silk paintings from Dunhuang. It is also one of the most important because the central inscription in Tibetan and Chinese, although almost completely faded when first seen, can be read and does provide a date. This inscription (see below) had not been read when Waley catalogued the Stein collection, but has recently been revealed by infra-red photography (Fig.43) and published by Heather Karmay in her book on Early Sino-Tibetan Art. Her translation of the Tibetan part reads as follows:In the year of the dragon, I, the monk dPal-dbyangs, painted in a group the images of Bhaisajyaguru; Samantabhadra; Mañjusri-kumara; a thousand-armed, thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara; Chintāmanicakra; Parina-tacakra etc., for the benefit of my health and to transfer the merit (?) (created by the act of painting, to all beings).The Chinese inscription, in nine columns from left to right, repeats the substance of the Tibetan part, but is more specific as to date. More of the text can be made out than when it was published by Karmay: 建造畢 丙辰歲九月癸卯朔十五日丁巳 □共登覺路 □□□法界蒼生同 以此功德奉爲先亡□# 空羂索一軀 千眼一軀如意輸一軀不 一鋪文殊普賢會一鋪千手 敬畫藥師如來法席Respectfully painted one group of Bhaisajyaguru on his dharma seat; Mañjusrī, Samantabhadra and their assemblies, one group; thousand-armed, thousand-eyed (Avalokitesvara), one group; Cintāmanicakra, one group; Amoghapāsa, one group; through this to acquire merit on behalf of his deceased (father and) mother…to be reborn in the Dharmadhatu …together ascend the way of enlightenment. The year bingchen, ninth moon guimao, the first fifteen (days), the day dingsi, executed and completed.This inscription is set in the very centre of the painting as it survives today, rather than below as with most of the silk paintings. Both the Chinese and the Tibetan texts agree in giving precedence to Bhaisajyaguru (Pl.16-3), who presides over the whole in the top centre, accompanied by two Bodhisattvas and a numerous retinue. For the rest, the text confirms what is already fairly clear from the painting. Below, on either side of the inscription, Samantabhadra and Mañjusrī are clearly recognizable by their vehicles (Pls.16-4,16-5),while at the bottom Avalokitesvara (Fig.46) in the centre can be seen to be accompanied on the left by one of his transformations, Cintamanicakra (Fig.45),with the missing figure on the right identified by the Chinese text as yet another form of Avalokitesvara, Amoghapāsa. The popularity of Mañjusrī and Samantabhadra in the period of Tibetan domination at Dunhuang is attested to by many wall paintings, and the great size of Avalokitesvara here demonstrates his popularity also. The painting is indeed identified as a mandala of Avalokitesvara by Waley, supported by Karmay, but I prefer the precedence which the dual inscription seems to give to Bhaisajyaguru. Perhaps this is not so much the paradise of the Medicine Buddha, however, as a composite reflecting the personal predilections of the Tibetan monk who commissioned the painting.Not only the dual inscription in Tibetan and Chinese, but the painting itself reveals its Tibetan connections, for here in the same composition we find, as Heather Karmay has pointed out,”two quite different styles that existed side by side in Dunhuang. The first, in which the main body of the painting is painted, is in Chinese style, and the second, confined to the portrayal of the Bodhisattvas on either side of Bhaisajyaguru, may be directly associated with the group of Tibetan paintings [from Dunhuang].” In fact, of course, it is not so much two different styles as the integration of two different modes of depiction that we find here, since the actual means-line and colouring-is exactly the same for both types of figure. The initial drawing is in pale ink, still quite easily discernible in details such as the eyebrows. Over this is the white of the skin colour, with slight shading in pink. Finally, outlines such as those of the eyebrows, mouth and major drapery lines are drawn again in a darker ink, or, in the case of the hands and fingers, ears and nose, in red. These represent common stylistic elements which are, I think, sufficient to show that the same artists were at work here. Where the figures differ is in their attitudes, in the configuration of their facial features, and in the clothes that they wear. The two chief Bodhisattvas above, lightly clothed in the Indian manner, are seated with one leg pendent, the body swaying to one side, the head not only inclined in the opposite direction but also lengthened on the one side and foreshortened on the other, while the hair falls in many small ringlets over the shoulders. This is in contrast to the demurely clothed figures of Manjusri and Samantabhadra below, although they also are seated with one leg pendent. They have almost symmetrical faces and long smooth locks of dark hair framing the shoulders and arms.In some ways the painting appears to be midway between a mandala and the usual type of paradise painting with an architectural setting. There is a landscape background, clearly visible in the upper left (Pl.16-7)and originally in the right corner also. This can just be seen to have extended behind the central Buddha group also, and the latter is flanked by now-faded plantain trees. The space around is sparsely filled with flowering plants, but there are dividing lines of tiles also, suggesting a rectangular platform for the main group and dividing the middle assemblies of Manjusri and Samantabhadra from the triad at the bottom. Some of the most charming details are the small figures of flying apsarasas around the canopies of these two Bodhisattvas; in addition one attendant on either side holds a staff from the top of which flies a panelled banner with streamers. These two great assemblies, like the apsarasas and the smaller groups of sixteen and eighteen seated figures above them (Fig.44), are essentially supported on clouds which issue out of the landscapes above. All are shown advancing towards the centre. The triad below is static, dominated by the geometric forms of the multiple arms of Avalokitesvara and the great white red-bordered circles of the haloes of Cintamanicakra and Amoghapasa.As explained by Karmay, the only bingchen year to fall within the period of Tibetan domination at Dunhuang corresponds to A.D.836. Among the sutra manuscripts also, those of this period which bear dates commonly lack any indication of the Chinese reign period, and are dated, as one might expect, by the cyclical combination alone. As the style, too, is manifestly of the ninth century, and the depiction of Manjusri and Samantabhadra not far removed from such a securely dated example as Pl.23, this date can be regarded as reliable and of considerable value in understanding the development of painting at this time. Chinese From Whitfield 1982:儘管下邊大半部分已缺失,但該繪畫仍屬敦煌絹繪中超大型作品之一。說其重要是因爲在中央部位有吐蕃和漢文對照的題記,因為褪色,肉眼幾乎無法看清,但仍可識讀,並提供年代。Waley編寫斯坦因收集的敦煌繪畫目錄时,尚不能解讀此題記,而近年通過紅外線拍照才達到解讀的可能(參見Fig.43)。Heather Karmay在其著作《早期中原與西藏藝術》(Early Sino-Tibetan Art)中有介紹,她将吐蕃文解讀如下:辰年,我,比丘dPal-dbyangs,繪藥師如來、普賢、文殊、千手千眼觀音、如意輪觀音、不空羂索觀音等諸像,爲了自身的健康並宣揚佛法(通過繪像普渡衆生)。漢文題記是從左到右豎寫的,共九行,內容與吐蕃文重復,年代標記更爲明確。現在,此漢文題記比Karmay發表時解讀的更爲詳細。建造畢丙辰歲九月癸卯朔十五日丁巳□共登覺路□□□法界蒼生同以此功德奉爲先亡□考空羂索一軀千眼一軀如意輪一軀不一鋪文殊普賢會一鋪千手敬畫藥師如來法席這些題記,不像其他很多繪畫那樣記在下方,而是在現存畫面大致中央的位置上,因而保存至今。漢文和吐蕃文兩方題記一致推崇的藥師如來(參見圖16-3),随帶二脅侍和衆多眷屬坐于上部中央,統轄整个畫面。其他諸像雖然在畫面上均可判別,但題記更能幫我們確認。下方題記兩側是普賢和文殊菩薩,可以從他們的坐騎很容易做出判斷(參見圖16-4,16-5)。另,下段中央是千手千眼觀音(參見Fig.46),左邊伴有觀音變身之一的如意輪觀音(參見Fig.45),右邊残缺的像,通過漢文題记可以判斷是另一觀音變身:不空羂索觀音。吐蕃時期,敦煌地區流行文殊和普賢,從石窟壁畫的諸例也可證明。這幅畫中的觀音佔據了較大的空間,也可確認觀音的流行。Waley確認此畫為觀音曼荼羅,Karmay也支持這个觀點,而我是從合璧的文字題記中藥師如來的優越地位得到確認的。其實,此畫並不是完全按藥師淨土圖的形式製成的,恐怕是按照吐蕃僧人帶有個人喜好的要求而製作的作品。不僅題記是吐蕃文和漢文合璧,繪畫表現上也有吐蕃化的成分。有關兩種形式的融合,我們也從畫面上可以看到。這一點正如Heather Karmay已經指出的,“……在敦煌,有兩種完全不同的形式共存。首先是繪畫的主要图像體現了完全中國化的形式,其次是在[敦煌]的一系列藥師的兩脅侍菩薩與吐蕃有緊密联係。”當然,實際上我們在這裏看到的,與其說兩種不同形式的共存,還不如說兩種不同圖像表現的統一。在兩種圖像中,線條和顔色均採用了完全一致的手法。比如可清楚辨认的眉的部分,用薄墨描下線;皮膚塗白色,用粉色薄薄晕染;施彩後,眉、口以及衣褶等均用濃墨描出,而手和指、耳朵等卻用紅色線。因爲兩种圖像都存在這種共同的表現方式,所以,可以充分肯定在該畫是由同一組畫家製作的。圖像表現不同的地方,體現在那些姿態上,即容貌和身上的衣裳的區別上。上邊的二脅侍菩薩著印度風格的輕衣,結半跏趺姿勢而坐。不僅身體向一邊扭,頭側向反面,頭的一側也顯得稍長,反側略短,有深度感。一方面,披在肩上的頭髮,髮梢形成小卷。這與下面同樣結半跏趺,姿勢端正的文殊和普賢的形成對比。文殊和普賢的面部幾乎是左右對稱的,頭髮長而平滑,可見多處結,從肩上懸到手腕。該畫的內容,按慣例位置應在配有建築物的淨土圖和曼荼羅之間。左上部的風景(參見圖16-7)尚殘留,當初在右上部也應繪有同樣的風景。另外,藥師三尊和眷屬背後一帶也應繪有風景,月光菩薩左邊略微残留的阔葉植物想必是那風景構圖的一部分。其周邊的空白處分佈稀疏的花草,上方藥師三尊群體所乘坐的寶台、中段文殊以及普賢菩薩群體和下段三尊群體的分界線是排列的磚。此畫有很多富有魅力的細節,尤其引人注目的有圍繞文殊和普賢華蓋上空起舞的小飛天,以及文殊和普賢各有一位随從手握帶著流蘇的幡竿。文殊、普賢兩群體上方的由十六~十八身小型坐像組成的群體(參見Fig.44),像飛天一樣,乘着雲從上方飞來,他們看似是向中央前進。下段三尊是靜止的,以千手千眼觀音的衆手構成的幾何形背光、如意輪觀音和不空羂索觀音紅色邊緣的白色圓形背光,佔據了畫面的大半部分。如同Karmay說明的那樣,吐蕃時期,敦煌與丙辰年相應的是只有公元836年。在佛經中,吐蕃時期通常不使用中國年號,而是使用干支來標識年代。風格上很明顯是9世紀的作品,文殊和普賢的表現方式與有確切紀年的彩色圖版第23圖《四觀音文殊普賢圖》無大差別。因此,判斷此作品中的紀年“丙辰”为836年是可信的。在研究吐蕃時期敦煌繪畫的发展上,它是極其重要的作品。

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)