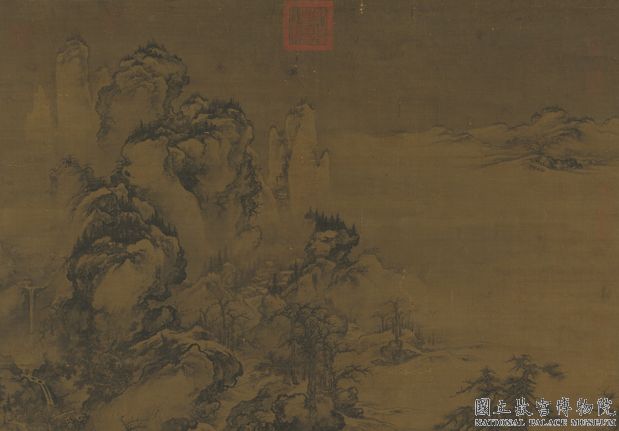

Period:Tang dynasty Production date:9thC

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise musician dancer palace/mansion 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 樂獅 (Chinese) 舞伎 (Chinese) 皇城 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 206 centimetres Width: 167 centimetres

Description:

Large, complex painting of the Paradise of Bhaiṣajyaguru (Buddha of Healing), arranged on terraces of a splendid Chinese palace. The Buddha is seated at the centre, surrounded by Bodhisattvas and attendants making offerings. At the top, to the left and right, are the Bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara with a thousand hands and Mañjuśrī, the Buddha of the Future Era, with a hundred bowls. Curtains and trees, lakes with golden sands, birds and lotuses. Dancers and musicians, bodhisattvas and esoteric deities. The side scenes (identified by inscriptions) depict episodes of the Bhaiṣajyaguru Vaiduryaprabha Sutra. Ink and colour on silk. Inscribed.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000314_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00264436_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00520914_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Whole.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_1.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_2.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_3.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:Bhaisajyaguru, the Buddha of Healing, with his paradise in the East as a counterpart to the Western Paradise of Amitaabha, was, as Professor Soper has shown (Literary Evidence, p.173), a latecomer to the Buddhist pantheon. His two principal Bodhisattvas are modelled on those of Amitābha, but do not have the distinct personalities and individual popularity possessed by Mahāsthāmaprāpta and Avalokitesvara. Bhaisajyaguru himself seems to have evolved from a coalescing of two of his Bodhisattvas with similar names, and Soper suggests that his appearance, aided by a group of twelve yaksa deities, could have been a response to the healing miracles of Christ and the twelve apostles.Nevertheless, Bhaisajyaguru enjoyed a period of great popularity at Dunhuang, to which both this painting and Pl.16 bear witness. The present very large painting on silk is the equivalent of some of the most complex, though even larger, paradise scenes on the walls of the Dunhuang cave chapels. Its wealth of detail and fair state of preservation have led to the inclusion of many details as colour plates in this book, in order both to give a fair idea of its appearance and to provide the opportunity of comparing it with the wall paintings. After the briefest of visits to Dunhuang in September 1981,and from published reproductions and the photographs of the Lo Archive at Princeton, I can only say that some of the closest resemblances, in both composition and individual details, are to be found not at Dunhuang itself but at the smaller Yulin group of caves with painted decoration at Wanfoxia, near Anxi. These similarities will be discussed below.The whole composition is laid out just like the depiction of Sukhāvatī, or the Western Pure Land, corresponding to the description in the Wu liang shou jing 無量壽經,which speaks of seven rows of railings, with curtains and trees, seven lakes with golden sands and lotus flowers, music and singing birds, with Amitābha immeasurably bright and glorious in the centre. Here the Buddha is Bhaisajyaguru instead, but in all respects the depiction is modelled on the paradise of Amitābha. The railings and trees border the terraces on which the assembly appears, rising out of a foreground lake. Islands of golden sand, on which birds are displaying and singing (Pl.9-4), emerge from this lake, as do lotuses with tiny Bodhisattvas (Pl.9-8)and two more on which are naked newborn souls, still crouching in the foetal position. The main dancer, with flying ribbons and whirling scarves (Pl.9-3), is in the centre, immediately in front of the altar with its golden cakra on a golden tripod bowl. On either side of her, two infants also dance, and one of them plays on an hourglass drum. The other instrumentalists are seated. From the left they include the pipa琵琶,or lute; qin琴,or seven-stringed zither; pipa again; and konghou箜篌,or vertical harp; from the right, xiao簫,or end-blown flute; sheng笙,or mouth organ; dizi笛子,or transverse bamboo flute; and wooden clappers. In front of the dancer, a kalavinka, or bird with human head and arms, plays the cymbals and completes the ensemble. Other birds originally stood in front of this one but are now lost. Like the painting as a whole, this orchestra represents a blend of Chinese and Western elements, since the qin was the Chinese musical instrument held in highest esteem, while the pipa, of Western origin, has always been regarded as a foreign instrument and associated with gaiety and dance.Around the throne of the Buddha and the altar in front of it six kneeling figures make offerings(Pl.9-2).The two principal Bodhisattvas, Sunlight(on the right, holding a small standing figure who in turn holds the sun disc;Pl.9-11)and Moonlight (Pl.9-10),are surrounded by numerous other figures who include the four Lokapālas (Dhrtarāstra with lion-mask helmet alone recognizable by his lute;Pl.9-6), others with magnificent animal headdresses (phoenix, snake, dragon and peacock)and two demons, one of them holding a naked babe, a detail found also in the fragment Stein painting 178*(Vol.2,Pl.50).On the extreme left and right are standing triads of a Buddha and two Bodhisattvas, advancing to the railing of the terrace in welcome(Pls.9-8,9-9).Their scarves and stoles, particularly the long white sashes of the two Bodhisattvas holding offering bowls on which are flowers and a vase, are draped with conscious effect through and over the railings, in a manner that we shall see repeated in the banners featuring individual Bodhisattvas and Vajrapani(Pls.56-58).Below them on either side are side terraces, each with six of the twelve yaksa warriors who accompany Bhaisajyaguru(Pls.9-12,9-13).Splendid buildings form a background to the assembly. Above them, on layers of red and blue clouds, appear the figures of Avalokitesvara with a thousand hands, and Manjusri with a thousand bowls, of which the larger each contain a dhyani-buddha seated on the cosmic mountain (Pls.9-5,9-6).These esoteric figures are mirrored below by two further forms of Avalokitesvara, Chintamanicakra(Fig.25)on the left and another only identifiable by the dhyāni-buddha in the headdress and the water flask held in one of the hands. They were each accompanied by four figures, one playing a pipa, another holding a lotus, the rest largely lost through the extensive damage to the lower edge of the painting.The depiction of the Eastern Paradise is completed by the side scenes: on the right the Nine Forms of Violent Death (Pls.9-14,9-15,Fig.28)and on the left the Twelve Vows of Bhaisajyaguru (Fig.27).Not unnaturally the latter offered far less scope for imaginative illustration than the former. But like everything else in this paradise, the Violent Deaths bear a close resemblance to the Perils from which Avalokitesvara was the saviour, so that even here the contrived and derivative nature of Bhaisajyaguru and the overwhelming debt to Avalokitesvara and his spiritual father Amitābha are manifest.The resemblance between this painting and those at the Yulin caves is most marked in the case of the Amitābha paradise on the south wall of Cave 25,already recognized as having paintings of the Middle Tang period of particularly fine quality(Wenwu,1956/10,pp.11-13). There are close similarities not only in the disposition and style of the figures but also in minor details such as the trees and birds. It is these features that are perhaps the most telling, since although the conservatism of art at Dunhuang and nearby ensured that the main features of large compositions were enduring, this cannot have been so with small details that allowed the painters greater scope for personal preference or the exercise of observation or imagination. Thus, to take some examples, we may notice in particular the two-storeyed pavilions on either side (Pls.9-5, 9-6).In both the silk painting and the Yulin Amitabha paradise, these pavilions are flanked on either side by trees, the foremost of which have foliage disposed in tiers that partly cover the lower roofs .Following the kind of formula already established in China by the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, these trees have a double trunk which divides close to ground level, with a dead snag half-way up the larger limb. An elaborately finished wooden kang with a vacant lotus throne almost fills the interior of the ground floor. On the upper storey some of the blinds in both paintings are still lowered, and others raised. On the left in the silk painting there is a charming glimpse of a gandharva or apsaras looking out, while another behind is raising the blind, head and shoulders concealed behind it. Across the painting at the same level a similar figure peeps around the corner of the building, and yet another has sat down on the balcony railing, holding on with both hands and leaning forward to avoid overbalancing. This figure, and perhaps the one rolling the blind also, finds an almost exact counterpart in the wall painting (Lo Archive, nos.3005-3006). All of them show a mastery of the convincing depiction of three-dimensional space as well as a nicety of observation of realistic details.As to the birds, in the Amitābha wall painting of Cave 25,a kalavinka and a large bird are seen on the terrace to the right and left of the main Buddha triad. All are displaying with open wings; the birds resemble swans and appear to be white, but the one on the right curiously has a peacock tail. In the silk painting (Pl.9-1), this space is filled with additional figures of the much more numerous Buddha assembly. The kalavinka, still with striped wings and billowing cloudlike tail, finds a new place in front of the dancing figure (Pl.9-3), and the large swan-like birds, one of which (on the right) is damaged but can just be seen to have had a peacock tail, stand on the golden islands in the foreground lotus pool (Pl.9-4). The parrots of the wall painting have likewise flitted to perches on the railings nearer the front of the painting.The architecture of the main buildings is among the most splendid of any of the silk paintings from Dunhuang, although not as elaborate as the still larger paradises from the wall paintings, for example, in Cave 172 (Dunhuang bihua, Pl.144). Nevertheless, the roof of the central gateway, immediately behind the Buddha, has triple tiers of brackets, with two slanting ang 昂,or cantilever arms, prominent and a third visible on close inspection at the corners, together with the round end of the eaves purlin. The intercolumnar supports are not easily visible at first but can be seen to be of confronting S-shape with elaborately foliated ends, rather than the archaic plain inverted V; they have not yet been replaced by further tiers of brackets as in the extant ninth century hall at the Foguangsi, Wutaishan. In the painting, this gateway has a single roof. Right behind it, in a paler red, can be seen the eaves of the first-storey roof of the main hall, clearly a free-standing structure. This is crowned by a terrace and a second roof of which only one corner is properly visible, due to the loss of a major section of the painting at this point. Just enough is visible to show that this roof has similar bracketing to that of the gateway, but lacks the slanting ang. A verandah runs from the gateway, turns behind the side pavilions, and apparently runs continuously behind the main hall, with extensions to right and left behind the drum and bell pavilions, suggesting an extensive series of courtyards. The interior walls are white, with green windows and a blue floor with tiled edging and tiled surround to the well of the courtyard. Here four Bodhisattvas stand on individual lotus pedestals. Further vitality is given to the lofty features of the architecture and the canopies by the long scarves of the apsarasas and the coloured plumes that support them in an aerial dance, winding in and out between the roofs and around the canopies. The white walls and the red columns are a constant theme; green ridges on dark blue or blue roofs alternate with blue ridges on green roofs to make quite clear the division of parts.Turning to the side scenes, the resemblances with the wall paintings here appear perhaps not so much in terms of exact parallels in depiction as in the choice of scenes taken directly from daily life. We may take as examples a banquet scene from the Maitreya paradise on the north wall of Cave 25 at Wanfoxia(Lo Archive,no.3020)and scenes from the right margin of the silk painting such as the falconer with his hound—“When intent upon hunting, sports, women or wine, to have one’s strength and will stolen by a demon”(Pl.9-14,the Third Form of Violent Death)—and the eloquent death-bed scene with monks and laymen alike reciting the scripture of Bhaisajyaguru from yellow scrolls while the sufferer lies on a kang supported by his wife(Fig.28). All are vividly observed and appear as close reflections of contemporary life. As for the landscapes, resemblances can certainly be found, for instance in the overhanging cliff just within the main scene of the wall painting in the top right corner (Lo Archive, no. 3006) and the cliff from which a man is falling in the right margin of Stein painting 36(Pl.9-15). The landscape at the top of the right margin, with a tree-covered island in front of a steep valley, is outlined in ink, with shading above the contour lines, just as in the landscapes at the top of the Maitreya paradise in Cave 25 (Flying Devis, 1980, Pl.74).Such close similarities are both evidence of the constant dependence of the Bhaisajyaguru paradise on that of Amitābha and a vivid reminder of how rapidly motifs in Buddhist art could spread and of the uses to which paintings such as the one under discussion could be put, since we must assume either that there were models brought from Dunhuang to serve as guides for the painters at Wanfoxia, or that the painters themselves, as is more likely, travelled there to carry out the work.While preserving the same general proportions as some of the paintings already discussed above (Pls.7 and 8), this painting is much larger. This has been achieved by the use of three complete widths of silk each around 56 cm wide, so giving a total width that is half as large again as either of the above. This seems to have been the largest size of silk painting to have been produced at Dunhuang. Besides the present example,Pls.15,16,18 and 19 are all of similar dimensions, not to mention others in New Delhi and the Musée Guimet. Since the narrative side panels are only very slightly wider than in Pl.8, there is a much larger central area that enabled the painters to depict a more numerous assembly around the central Buddha and to give the whole scene an even more ambitious architectural setting. In addition, in the present case, a mandala-like appearance is given to the whole by the inclusion, in the upper and lower corners, of four deities from the pantheon of Esoteric Buddhism (Pls.9-5, 9-6,Figs.25, 26).Finally, as regards the dating of the painting, although it has seemed appropriate to consider it in conjunction with the other paradise paintings of early ninth century date (such as Pls.8 and 11), it seems that it may in fact date from somewhat later in the ninth century. Without more detailed comparison with the wall paintings an exact dating is not possible, but the landscape details, in which the trees and their leaves begin to be reduced to a formula, and the new stiffness of the bright white sashes, elegantly twisting over the railings on the lotus pedestals, are evidence of the increasing mannerism that followed Dunhuang’ s isolation in the period of Tibetan domination and thereafter.Note on kalavinka: In the Sanskrit text of the Sukhāvatī-vyūha, there is simply a list of birds: hamsa (goose),krauñka (curlew), mayūra(peacock) ,suka(parrot),sālika(mynah)and kokila (cuckoo).In Kumārajīva’s translation this list appears as white goose, peacock, parrot, mynah, kalavinka and gongming zhi niao 共命之鳥 (jīva-jīva,or bird with two heads.) In the paradise paintings from Dunhuang, swans, peacocks and parrots are readily identified; kalavinkas are represented more in the form of the Indian kinnara, or musician with the wings and legs of a bird and a billowing tail. A jīva-jīva, shown as a bird with two human heads, can be seen in Fig. 38. (Taishō Daizōkyō, vol. 12,no.366, p.247a.) ChineseFrom Whitfield 1982:與西方淨土阿彌陀相應的是藥師如來的東方淨土,如Soper教授所講的那樣(參見Literary Evidence p.173),是佛教萬神殿中較晚登場的如來。藥師的二脅侍菩薩也是仿效阿彌陀的,但不像阿彌陀的二脅侍菩薩觀音和勢至那麽具有鮮明的性格,也沒有那麽受歡迎。藥師如來似乎是基於藥王和藥上兩菩薩而成的。 Soper教授指出,以十二神將做眷屬的藥師佛的功能,可以與基督及十二使徒的醫療奇迹相比。不過藥師信仰曾在敦煌地區極為流行,本圖和圖16則是見証。本圖所繪,作爲絹畫是非常之大,在構圖方面可與敦煌石窟壁畫中最複雜的淨土圖相匹敵,至於大小,壁畫則更大。對細部的描寫非常出色,保存狀態也好,所以在本書彩色圖版中刊載了很大一部分,使繪畫的各個局部最大可能地得到展現,這既有利於探討它出現的原因,也有利於與壁畫進行比較。筆者曾於1981年9月到敦煌作過短暫的訪問,依據出版的圖錄和普林斯頓大學羅寄梅檔案的照片資料,不是在敦煌石窟中,而是在比敦煌石窟規模要少得多的安西近郊萬佛峽榆林窟中,發現在構圖和細部的描寫方面與其極相近的淨土圖。關於那些類似之處,將於後面詳細討論。整體結構的設置與西方淨土的刻畫是完全一樣的,西方淨土是根據《無量壽經》而形成的,經中說:七重欄楯,七重羅網,七重行樹,皆是四寶周匝圍繞。極樂國土有七寶池,池底純以金沙布地以及蓮花、音樂、唱歌的小鳥,阿彌陀如來坐在無量光明的淨土中央。在此圖中,除了藥師代替了阿彌陀如來,其餘的描繪均模仿阿彌陀淨土。聖衆站立的若干寶台被勾欄和樹木隔開,突現于前景的池中。金沙島上鳥兒展翅歌唱(圖9-4),蓮花漂浮在池中,载着小菩薩(圖9-8),有兩個以上的菩薩是以胎兒姿勢蹲坐的新生裸體幼兒。畫面中央的祭壇上,擺放着置於三足盤上的金色香爐。正中有挥動着飄帶、旋转着披肩跳舞的舞伎(圖9-3)。其左右有兩個跳舞的童子,其中一人拍打着胸前懸挂的鼓。其餘樂伎則坐着,左側依次演奏琵琶、七弦琴、琵琶、箜篌等樂器,右側依次演奏簫、笙、笛子、拍板等樂器。舞伎前方,人首鳥身的迦陵頻伽敲着鐃鈸,組成一個大合奏。其前面原來還應有一只鳥,現在已殘缺。畫面的整體印象是,這個樂隊融合了中西两方面的文化要素。琴是中國最受珍重的樂器,而琵琶是起源于西方,通常被看成是外來樂器,正是這些樂器造就了熱烈的舞蹈氣氛。如來寶座的周圍以及祭壇的前方有跪着手捧供物的六尊菩薩(圖9-2圖)、二脅侍菩薩、日光菩薩(9-11圖,右手捧日輪圓盤的小立像)和月光菩薩(圖9-10),周圍則是包括四大天王(持國天王,可以從身著獅子兜、手持琵琶判斷。圖9-6)在內的其他諸像,如頭戴聖獸冠(鳳凰、蛇、龍、孔雀等)的諸像、二尊魔鬼像,其中一身懷抱裸體嬰兒,斯坦因繪畫(Stein painting)178(第二卷,圖50)的绢畫斷片中也有發現。左右兩端的寶臺上有一組一佛二菩薩立像,走近勾欄以示迎接(圖9-8,9-9)。其二脅侍菩薩的披肩和飄帶,尤其是手捧装花托盘的菩薩、手捧装寶瓶托盘的菩薩身上的白色的長飾帶,有意製成褶皺狀,穿過並垂懸在勾欄上。將菩薩或金剛力士作爲個體單獨描繪的幡畫中也有這種表現形式(圖第56-58)。三尊立像正下方的左右寶臺上,每側六尊神將,總共十二尊,護衛藥師(圖9-12,9-13)。聖衆背後配有壯麗的建築物,上方描繪有乘坐赤、青彩雲的千手觀音和千缽文殊。其中有若干大缽,裏面是須彌山,佛坐在上面(圖9-5,9-6)。畫面下端也有兩處類似密教的圖像,左邊是如意輪觀音(參見Fig.25),右邊聖像從頭戴化佛寶冠、左手持淨瓶等標誌可以判斷是不空羂索觀音(參見Fig.26)。每像應有隨從四身,一身爲彈琵琶、一身爲手持蓮花,由於畫面下端已損,無法確認另外二身。此東方琉璃光淨土因右側邊緣的“九橫死”(參見圖9-14,9-15,Fig.28)、左側邊緣的“藥師十二大願”(參見Fig.27)的故事畫而得以完整的體現。原本“藥師十二大願” 的想象空間沒有“九橫死”豐富,然而任何一幅藥師淨土圖中,所有“九橫死”都和觀音救助危難時的風格極其相似,所以藥師如來特性的形成深受觀音及其主尊阿彌陀如來的影響是顯而易見的。此繪畫與榆林窟第25窟南壁已經被確認為中唐的特別優秀的阿彌陀淨土圖非常相似(參見《文物》1956年第10期11~13頁),不僅諸尊的佈局和風格,而且諸如樹、鳥等細部的刻畫也極其相似。之所以要特別舉出這一點,是因爲從敦煌及其附近的美術品中,主要畫面的表現方式已趨保守並有延續,而在微細的部分,則有充分的餘地以便畫家發揮自己的經驗、觀察力及想象力。如此,舉個例子,我們特別觀察一下兩端的二層樓閣(參見圖9-5,9-6)。無論是這幅絹畫還是榆林窟的阿彌陀淨土圖,樓閣兩側均植有樹木,幾叢茂密的樹葉遮住了下层楼的屋頂。這些樹木的處理方式承襲了南北朝就已經固定了的風格,樹幹離地很近開出兩叉,粗枝中間有殘枝。樓閣一層內,細心製作的木結構須彌壇幾乎填滿了一間房子,上面放置着無人乘坐的蓮花座。上層的簾子,兩幅畫中都是有些卷起,有些垂下。絹畫左側的樓閣中可以见到朝外看的乾闥婆或者天女可愛的身影,其背後另有一位正在卷簾,頭和肩遮隐在簾後。將目光平移到右邊樓閣,則可以看到從建築物後面側身探出同樣的像,而另一個則坐在勾欄上兩手扶著,身子向前傾斜,以保持平衡。在壁畫中也能見到大致類似的情景(參見羅寄梅檔案No.3005,3006)。這些足以說明說明畫家細部写實的細致入微的觀察力和三維空間的刻畫已經達到爐火純青的程度。第25窟壁画的阿彌陀淨土圖中,阿彌陀三尊左右的寶臺上出現迦陵頻伽和大鳥各一組,每一組都展翅欲飛。鳥非常像天鹅,白色,右邊的鳥居然有奇妙的孔雀尾。而在此絹繪图中(圖9-1),這個位置則被多尊聖像占滿。迦陵頻伽的羽毛是條紋形,尾巴似波狀雲,位置則被挪到舞伎的前邊(參見圖9-3)。另外,天鵝一樣的大白鳥,其中一隻(右邊)已損壞,只留有像孔雀尾的站立在前景蓮池中的金沙島上(參見圖9-4)。在壁畫里,有鸚鵡飛落在畫面前方的勾欄上。敦煌絹畫中主要建築雖不如敦煌壁畫中的建築壯觀,如第172窟壁畫中的淨土圖(參見《敦煌壁畫》圖第144)。不過,如來正後方門樓的屋頂,則清楚地見到三組斗栱中有二層昂,細細觀察則發現兩角斗栱也有三層的昂,連圓檁子的頂端都表現得很清楚。柱間蜀柱最初看到的是兩個相對的尾飾葉紋的“S”形而不是帶有古風的倒“V”字形。不過,它還沒有被五臺山佛光寺9世紀大殿中所見的跳出更深的斗栱所取代。此處繪的是門樓的單層屋頂。其正上方所見的淡紅色的軒,顯然是一個獨立建築物的底層。那建築物是圍繞著勾欄的二層樓閣,因爲這部分畫面大幅破損,只能看見一角。可看到其屋頂與門樓有同樣的斗栱組合,屋頂上見不到昂。從門延伸出的長廊,繞過兩翼樓閣的背後,一邊明顯通到中堂,另一邊則延伸到左右的鼓樓和鐘樓的後邊,體現出庭院的開闊。白色的內壁,綠色的窗戶,青色的地板,院落邊緣及水池四周貼磚。四身菩薩分別踏立於蓮花座上。更生動的是,在高高聳起的建築物、華蓋上面,有身著長衣的飛天在空中起舞,拖着長長的飄帶,在層層疊疊的屋頂間和華蓋中忽隱忽現。通常的白牆赤柱沒有變化,但爲了清楚區分屋頂,青色屋頂的邊緣採用綠色,綠色屋頂的邊緣採用青色,相互交替搭配。再看邊緣部分,與壁畫有很強的的相似性,场景的刻畫都是直接取自現實的日常生活。我們可以用萬佛峽第25窟北壁彌勒淨土圖的宴會場面(參見羅寄梅檔案No.3020)做個例子,此繪畫右側邊緣的牽著獵犬的鷹獵者—— “打獵、競技、婦人、酒等,心力被鬼神所奪” (參見圖9-14,“橫死第三”)——富于表情的臨終時的場面、比丘和世俗男子好像在誦讀黃色經卷《藥師經》、病人臥在炕上被妻子攙扶著等場景,都栩栩如生,觀察的細致入微,是當時生活的真實寫照。至于山水,如壁畫上方右角半空中突起的懸崖(參見No.3006)和斯坦因繪畫36右側邊緣男子跳下的懸崖(參見圖9-15)等處,均可看出類似的地方。繪畫右側邊緣上端峻峭山谷前的樹木覆蓋的島嶼,是用墨色的線和晕染描繪的,與第25窟彌勒淨土圖(參見《敦煌飛天》圖74)上端所描繪的山水圖相同。此繪畫和榆林窟壁畫如此相似,說明藥師淨土圖是仿照阿彌陀淨土圖的同时,也為正在探討的佛教美術的題材是如何迅速傳播與使用的问题提供了生動的资料。因為我們必須假定是敦煌粉本傳到萬佛峽作爲那裏畫家的底本,或者是敦煌畫家親赴那裏從事壁畫製作的。前面已經討論過尺幅相當的兩幅繪畫(參見圖7,8),這幅畫則更大。它是用三幅幅寬爲56cm左右的絹子组成,整個畫面的幅寬比上面兩個作品寬約1.5倍。這可能是敦煌所製作的絹畫中最大的作品。與其大小大致相同的作品還有圖15、16、18和19,沒有將新德里國立博物館和集美博物館的作品列在裏面。邊緣故事圖的幅寬僅略大於圖8,所以中間部位極其寬闊,作者在那裏畫入衆多圍繞主尊的聖衆,還給整個畫面配上了雄偉的建築物。另外,此畫的上下四角還配有四尊密教萬神殿的神祗,使整個畫面具有曼陀羅式的氛圍(參見圖9-5,9-6,Figs.25,26)。最後,關于此畫的年代。盡管該畫与9世紀初淨土變密切相關(諸如圖8、11),實際上這幅畫可能在9世紀稍後的時期內。如果不與壁畫進行詳細比較,則無法判断出正確的年代。觀察山水的細部,樹木、枝葉已經開始形式化,描繪蓮池的勾欄上优雅地纏着的白色綬帶的线条,顯出僵化的苗頭,使我們感覺到,這是吐蕃時期敦煌与世隔绝後,已經公式化了的現象。注迦陵頻伽:在梵文《佛說阿彌陀經》,為一組鳥:鵝、麻鷸、孔雀、鸚鵡、八哥、杜鵑,鳩摩羅什譯為:白鵠、孔雀、鸚鵡、舍利、迦陵頻伽、共命之鳥(一鳥二頭)。在敦煌淨土畫中,天鵝、孔雀、鸚鵡非常容易識別。迦陵頻伽,在印度是一種妙聲鳥,有鳥的翅膀和腿,波浪狀的尾巴。共命之鳥,表現為兩個人頭的鳥,可參看Fig.38(《大正藏》,卷12,no.366,p.247a)。 Zwalf 1985The Buddha of Healing, a latecomer to the Buddhist pantheon, with his Eastern Paradise, enjoyed great popularity at Dunhuang. This large painting is the equivalent of some of the most complex and even larger paradise scenes on Dunhuang cave walls and is laid out like a depiction of Sukhāvatī, the Western Pure Land. Around the Buddha six figures make offerings. The Bodhisattvas Sunlight and Moonlight are surrounded by figures including the four Lokapālas and two demons. Above, on layers of red and blue clouds, appear Avalokiteśvara with 1,000 hands and Mañjuśrī with 1,000 bowls. The Eastern Paradise is completed by side scenes – the Nine Forms of Violent Death (right) and the Twelve Vows of Bhaiṣajyaguru (left). These side scenes and the twelve ‘yakṣa’ warriors in two groups on side terraces in the foreground distinguish the paradise of the Buddha of Healing from the Western Paradise of Amitābha on which it is closely modelled.

Materials:silk, 絲綢 (Chinese),

Technique:painted

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva paradise musician dancer palace/mansion 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 淨土 (Chinese) 樂獅 (Chinese) 舞伎 (Chinese) 皇城 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 206 centimetres Width: 167 centimetres

Description:

Large, complex painting of the Paradise of Bhaiṣajyaguru (Buddha of Healing), arranged on terraces of a splendid Chinese palace. The Buddha is seated at the centre, surrounded by Bodhisattvas and attendants making offerings. At the top, to the left and right, are the Bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara with a thousand hands and Mañjuśrī, the Buddha of the Future Era, with a hundred bowls. Curtains and trees, lakes with golden sands, birds and lotuses. Dancers and musicians, bodhisattvas and esoteric deities. The side scenes (identified by inscriptions) depict episodes of the Bhaiṣajyaguru Vaiduryaprabha Sutra. Ink and colour on silk. Inscribed.

IMG

![图片[1]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00000314_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00264436_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_00520914_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Whole.jpg)

![图片[5]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail.jpg)

![图片[6]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_1.jpg)

![图片[7]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_2.jpg)

![图片[8]-painting; 繪畫(Chinese) BM-1919-0101-0.36-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/Paintings/mid_RFC643_Detail_3.jpg)

Comments:EnglishFrom Whitfield 1982:Bhaisajyaguru, the Buddha of Healing, with his paradise in the East as a counterpart to the Western Paradise of Amitaabha, was, as Professor Soper has shown (Literary Evidence, p.173), a latecomer to the Buddhist pantheon. His two principal Bodhisattvas are modelled on those of Amitābha, but do not have the distinct personalities and individual popularity possessed by Mahāsthāmaprāpta and Avalokitesvara. Bhaisajyaguru himself seems to have evolved from a coalescing of two of his Bodhisattvas with similar names, and Soper suggests that his appearance, aided by a group of twelve yaksa deities, could have been a response to the healing miracles of Christ and the twelve apostles.Nevertheless, Bhaisajyaguru enjoyed a period of great popularity at Dunhuang, to which both this painting and Pl.16 bear witness. The present very large painting on silk is the equivalent of some of the most complex, though even larger, paradise scenes on the walls of the Dunhuang cave chapels. Its wealth of detail and fair state of preservation have led to the inclusion of many details as colour plates in this book, in order both to give a fair idea of its appearance and to provide the opportunity of comparing it with the wall paintings. After the briefest of visits to Dunhuang in September 1981,and from published reproductions and the photographs of the Lo Archive at Princeton, I can only say that some of the closest resemblances, in both composition and individual details, are to be found not at Dunhuang itself but at the smaller Yulin group of caves with painted decoration at Wanfoxia, near Anxi. These similarities will be discussed below.The whole composition is laid out just like the depiction of Sukhāvatī, or the Western Pure Land, corresponding to the description in the Wu liang shou jing 無量壽經,which speaks of seven rows of railings, with curtains and trees, seven lakes with golden sands and lotus flowers, music and singing birds, with Amitābha immeasurably bright and glorious in the centre. Here the Buddha is Bhaisajyaguru instead, but in all respects the depiction is modelled on the paradise of Amitābha. The railings and trees border the terraces on which the assembly appears, rising out of a foreground lake. Islands of golden sand, on which birds are displaying and singing (Pl.9-4), emerge from this lake, as do lotuses with tiny Bodhisattvas (Pl.9-8)and two more on which are naked newborn souls, still crouching in the foetal position. The main dancer, with flying ribbons and whirling scarves (Pl.9-3), is in the centre, immediately in front of the altar with its golden cakra on a golden tripod bowl. On either side of her, two infants also dance, and one of them plays on an hourglass drum. The other instrumentalists are seated. From the left they include the pipa琵琶,or lute; qin琴,or seven-stringed zither; pipa again; and konghou箜篌,or vertical harp; from the right, xiao簫,or end-blown flute; sheng笙,or mouth organ; dizi笛子,or transverse bamboo flute; and wooden clappers. In front of the dancer, a kalavinka, or bird with human head and arms, plays the cymbals and completes the ensemble. Other birds originally stood in front of this one but are now lost. Like the painting as a whole, this orchestra represents a blend of Chinese and Western elements, since the qin was the Chinese musical instrument held in highest esteem, while the pipa, of Western origin, has always been regarded as a foreign instrument and associated with gaiety and dance.Around the throne of the Buddha and the altar in front of it six kneeling figures make offerings(Pl.9-2).The two principal Bodhisattvas, Sunlight(on the right, holding a small standing figure who in turn holds the sun disc;Pl.9-11)and Moonlight (Pl.9-10),are surrounded by numerous other figures who include the four Lokapālas (Dhrtarāstra with lion-mask helmet alone recognizable by his lute;Pl.9-6), others with magnificent animal headdresses (phoenix, snake, dragon and peacock)and two demons, one of them holding a naked babe, a detail found also in the fragment Stein painting 178*(Vol.2,Pl.50).On the extreme left and right are standing triads of a Buddha and two Bodhisattvas, advancing to the railing of the terrace in welcome(Pls.9-8,9-9).Their scarves and stoles, particularly the long white sashes of the two Bodhisattvas holding offering bowls on which are flowers and a vase, are draped with conscious effect through and over the railings, in a manner that we shall see repeated in the banners featuring individual Bodhisattvas and Vajrapani(Pls.56-58).Below them on either side are side terraces, each with six of the twelve yaksa warriors who accompany Bhaisajyaguru(Pls.9-12,9-13).Splendid buildings form a background to the assembly. Above them, on layers of red and blue clouds, appear the figures of Avalokitesvara with a thousand hands, and Manjusri with a thousand bowls, of which the larger each contain a dhyani-buddha seated on the cosmic mountain (Pls.9-5,9-6).These esoteric figures are mirrored below by two further forms of Avalokitesvara, Chintamanicakra(Fig.25)on the left and another only identifiable by the dhyāni-buddha in the headdress and the water flask held in one of the hands. They were each accompanied by four figures, one playing a pipa, another holding a lotus, the rest largely lost through the extensive damage to the lower edge of the painting.The depiction of the Eastern Paradise is completed by the side scenes: on the right the Nine Forms of Violent Death (Pls.9-14,9-15,Fig.28)and on the left the Twelve Vows of Bhaisajyaguru (Fig.27).Not unnaturally the latter offered far less scope for imaginative illustration than the former. But like everything else in this paradise, the Violent Deaths bear a close resemblance to the Perils from which Avalokitesvara was the saviour, so that even here the contrived and derivative nature of Bhaisajyaguru and the overwhelming debt to Avalokitesvara and his spiritual father Amitābha are manifest.The resemblance between this painting and those at the Yulin caves is most marked in the case of the Amitābha paradise on the south wall of Cave 25,already recognized as having paintings of the Middle Tang period of particularly fine quality(Wenwu,1956/10,pp.11-13). There are close similarities not only in the disposition and style of the figures but also in minor details such as the trees and birds. It is these features that are perhaps the most telling, since although the conservatism of art at Dunhuang and nearby ensured that the main features of large compositions were enduring, this cannot have been so with small details that allowed the painters greater scope for personal preference or the exercise of observation or imagination. Thus, to take some examples, we may notice in particular the two-storeyed pavilions on either side (Pls.9-5, 9-6).In both the silk painting and the Yulin Amitabha paradise, these pavilions are flanked on either side by trees, the foremost of which have foliage disposed in tiers that partly cover the lower roofs .Following the kind of formula already established in China by the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, these trees have a double trunk which divides close to ground level, with a dead snag half-way up the larger limb. An elaborately finished wooden kang with a vacant lotus throne almost fills the interior of the ground floor. On the upper storey some of the blinds in both paintings are still lowered, and others raised. On the left in the silk painting there is a charming glimpse of a gandharva or apsaras looking out, while another behind is raising the blind, head and shoulders concealed behind it. Across the painting at the same level a similar figure peeps around the corner of the building, and yet another has sat down on the balcony railing, holding on with both hands and leaning forward to avoid overbalancing. This figure, and perhaps the one rolling the blind also, finds an almost exact counterpart in the wall painting (Lo Archive, nos.3005-3006). All of them show a mastery of the convincing depiction of three-dimensional space as well as a nicety of observation of realistic details.As to the birds, in the Amitābha wall painting of Cave 25,a kalavinka and a large bird are seen on the terrace to the right and left of the main Buddha triad. All are displaying with open wings; the birds resemble swans and appear to be white, but the one on the right curiously has a peacock tail. In the silk painting (Pl.9-1), this space is filled with additional figures of the much more numerous Buddha assembly. The kalavinka, still with striped wings and billowing cloudlike tail, finds a new place in front of the dancing figure (Pl.9-3), and the large swan-like birds, one of which (on the right) is damaged but can just be seen to have had a peacock tail, stand on the golden islands in the foreground lotus pool (Pl.9-4). The parrots of the wall painting have likewise flitted to perches on the railings nearer the front of the painting.The architecture of the main buildings is among the most splendid of any of the silk paintings from Dunhuang, although not as elaborate as the still larger paradises from the wall paintings, for example, in Cave 172 (Dunhuang bihua, Pl.144). Nevertheless, the roof of the central gateway, immediately behind the Buddha, has triple tiers of brackets, with two slanting ang 昂,or cantilever arms, prominent and a third visible on close inspection at the corners, together with the round end of the eaves purlin. The intercolumnar supports are not easily visible at first but can be seen to be of confronting S-shape with elaborately foliated ends, rather than the archaic plain inverted V; they have not yet been replaced by further tiers of brackets as in the extant ninth century hall at the Foguangsi, Wutaishan. In the painting, this gateway has a single roof. Right behind it, in a paler red, can be seen the eaves of the first-storey roof of the main hall, clearly a free-standing structure. This is crowned by a terrace and a second roof of which only one corner is properly visible, due to the loss of a major section of the painting at this point. Just enough is visible to show that this roof has similar bracketing to that of the gateway, but lacks the slanting ang. A verandah runs from the gateway, turns behind the side pavilions, and apparently runs continuously behind the main hall, with extensions to right and left behind the drum and bell pavilions, suggesting an extensive series of courtyards. The interior walls are white, with green windows and a blue floor with tiled edging and tiled surround to the well of the courtyard. Here four Bodhisattvas stand on individual lotus pedestals. Further vitality is given to the lofty features of the architecture and the canopies by the long scarves of the apsarasas and the coloured plumes that support them in an aerial dance, winding in and out between the roofs and around the canopies. The white walls and the red columns are a constant theme; green ridges on dark blue or blue roofs alternate with blue ridges on green roofs to make quite clear the division of parts.Turning to the side scenes, the resemblances with the wall paintings here appear perhaps not so much in terms of exact parallels in depiction as in the choice of scenes taken directly from daily life. We may take as examples a banquet scene from the Maitreya paradise on the north wall of Cave 25 at Wanfoxia(Lo Archive,no.3020)and scenes from the right margin of the silk painting such as the falconer with his hound—“When intent upon hunting, sports, women or wine, to have one’s strength and will stolen by a demon”(Pl.9-14,the Third Form of Violent Death)—and the eloquent death-bed scene with monks and laymen alike reciting the scripture of Bhaisajyaguru from yellow scrolls while the sufferer lies on a kang supported by his wife(Fig.28). All are vividly observed and appear as close reflections of contemporary life. As for the landscapes, resemblances can certainly be found, for instance in the overhanging cliff just within the main scene of the wall painting in the top right corner (Lo Archive, no. 3006) and the cliff from which a man is falling in the right margin of Stein painting 36(Pl.9-15). The landscape at the top of the right margin, with a tree-covered island in front of a steep valley, is outlined in ink, with shading above the contour lines, just as in the landscapes at the top of the Maitreya paradise in Cave 25 (Flying Devis, 1980, Pl.74).Such close similarities are both evidence of the constant dependence of the Bhaisajyaguru paradise on that of Amitābha and a vivid reminder of how rapidly motifs in Buddhist art could spread and of the uses to which paintings such as the one under discussion could be put, since we must assume either that there were models brought from Dunhuang to serve as guides for the painters at Wanfoxia, or that the painters themselves, as is more likely, travelled there to carry out the work.While preserving the same general proportions as some of the paintings already discussed above (Pls.7 and 8), this painting is much larger. This has been achieved by the use of three complete widths of silk each around 56 cm wide, so giving a total width that is half as large again as either of the above. This seems to have been the largest size of silk painting to have been produced at Dunhuang. Besides the present example,Pls.15,16,18 and 19 are all of similar dimensions, not to mention others in New Delhi and the Musée Guimet. Since the narrative side panels are only very slightly wider than in Pl.8, there is a much larger central area that enabled the painters to depict a more numerous assembly around the central Buddha and to give the whole scene an even more ambitious architectural setting. In addition, in the present case, a mandala-like appearance is given to the whole by the inclusion, in the upper and lower corners, of four deities from the pantheon of Esoteric Buddhism (Pls.9-5, 9-6,Figs.25, 26).Finally, as regards the dating of the painting, although it has seemed appropriate to consider it in conjunction with the other paradise paintings of early ninth century date (such as Pls.8 and 11), it seems that it may in fact date from somewhat later in the ninth century. Without more detailed comparison with the wall paintings an exact dating is not possible, but the landscape details, in which the trees and their leaves begin to be reduced to a formula, and the new stiffness of the bright white sashes, elegantly twisting over the railings on the lotus pedestals, are evidence of the increasing mannerism that followed Dunhuang’ s isolation in the period of Tibetan domination and thereafter.Note on kalavinka: In the Sanskrit text of the Sukhāvatī-vyūha, there is simply a list of birds: hamsa (goose),krauñka (curlew), mayūra(peacock) ,suka(parrot),sālika(mynah)and kokila (cuckoo).In Kumārajīva’s translation this list appears as white goose, peacock, parrot, mynah, kalavinka and gongming zhi niao 共命之鳥 (jīva-jīva,or bird with two heads.) In the paradise paintings from Dunhuang, swans, peacocks and parrots are readily identified; kalavinkas are represented more in the form of the Indian kinnara, or musician with the wings and legs of a bird and a billowing tail. A jīva-jīva, shown as a bird with two human heads, can be seen in Fig. 38. (Taishō Daizōkyō, vol. 12,no.366, p.247a.) ChineseFrom Whitfield 1982:與西方淨土阿彌陀相應的是藥師如來的東方淨土,如Soper教授所講的那樣(參見Literary Evidence p.173),是佛教萬神殿中較晚登場的如來。藥師的二脅侍菩薩也是仿效阿彌陀的,但不像阿彌陀的二脅侍菩薩觀音和勢至那麽具有鮮明的性格,也沒有那麽受歡迎。藥師如來似乎是基於藥王和藥上兩菩薩而成的。 Soper教授指出,以十二神將做眷屬的藥師佛的功能,可以與基督及十二使徒的醫療奇迹相比。不過藥師信仰曾在敦煌地區極為流行,本圖和圖16則是見証。本圖所繪,作爲絹畫是非常之大,在構圖方面可與敦煌石窟壁畫中最複雜的淨土圖相匹敵,至於大小,壁畫則更大。對細部的描寫非常出色,保存狀態也好,所以在本書彩色圖版中刊載了很大一部分,使繪畫的各個局部最大可能地得到展現,這既有利於探討它出現的原因,也有利於與壁畫進行比較。筆者曾於1981年9月到敦煌作過短暫的訪問,依據出版的圖錄和普林斯頓大學羅寄梅檔案的照片資料,不是在敦煌石窟中,而是在比敦煌石窟規模要少得多的安西近郊萬佛峽榆林窟中,發現在構圖和細部的描寫方面與其極相近的淨土圖。關於那些類似之處,將於後面詳細討論。整體結構的設置與西方淨土的刻畫是完全一樣的,西方淨土是根據《無量壽經》而形成的,經中說:七重欄楯,七重羅網,七重行樹,皆是四寶周匝圍繞。極樂國土有七寶池,池底純以金沙布地以及蓮花、音樂、唱歌的小鳥,阿彌陀如來坐在無量光明的淨土中央。在此圖中,除了藥師代替了阿彌陀如來,其餘的描繪均模仿阿彌陀淨土。聖衆站立的若干寶台被勾欄和樹木隔開,突現于前景的池中。金沙島上鳥兒展翅歌唱(圖9-4),蓮花漂浮在池中,载着小菩薩(圖9-8),有兩個以上的菩薩是以胎兒姿勢蹲坐的新生裸體幼兒。畫面中央的祭壇上,擺放着置於三足盤上的金色香爐。正中有挥動着飄帶、旋转着披肩跳舞的舞伎(圖9-3)。其左右有兩個跳舞的童子,其中一人拍打着胸前懸挂的鼓。其餘樂伎則坐着,左側依次演奏琵琶、七弦琴、琵琶、箜篌等樂器,右側依次演奏簫、笙、笛子、拍板等樂器。舞伎前方,人首鳥身的迦陵頻伽敲着鐃鈸,組成一個大合奏。其前面原來還應有一只鳥,現在已殘缺。畫面的整體印象是,這個樂隊融合了中西两方面的文化要素。琴是中國最受珍重的樂器,而琵琶是起源于西方,通常被看成是外來樂器,正是這些樂器造就了熱烈的舞蹈氣氛。如來寶座的周圍以及祭壇的前方有跪着手捧供物的六尊菩薩(圖9-2圖)、二脅侍菩薩、日光菩薩(9-11圖,右手捧日輪圓盤的小立像)和月光菩薩(圖9-10),周圍則是包括四大天王(持國天王,可以從身著獅子兜、手持琵琶判斷。圖9-6)在內的其他諸像,如頭戴聖獸冠(鳳凰、蛇、龍、孔雀等)的諸像、二尊魔鬼像,其中一身懷抱裸體嬰兒,斯坦因繪畫(Stein painting)178(第二卷,圖50)的绢畫斷片中也有發現。左右兩端的寶臺上有一組一佛二菩薩立像,走近勾欄以示迎接(圖9-8,9-9)。其二脅侍菩薩的披肩和飄帶,尤其是手捧装花托盘的菩薩、手捧装寶瓶托盘的菩薩身上的白色的長飾帶,有意製成褶皺狀,穿過並垂懸在勾欄上。將菩薩或金剛力士作爲個體單獨描繪的幡畫中也有這種表現形式(圖第56-58)。三尊立像正下方的左右寶臺上,每側六尊神將,總共十二尊,護衛藥師(圖9-12,9-13)。聖衆背後配有壯麗的建築物,上方描繪有乘坐赤、青彩雲的千手觀音和千缽文殊。其中有若干大缽,裏面是須彌山,佛坐在上面(圖9-5,9-6)。畫面下端也有兩處類似密教的圖像,左邊是如意輪觀音(參見Fig.25),右邊聖像從頭戴化佛寶冠、左手持淨瓶等標誌可以判斷是不空羂索觀音(參見Fig.26)。每像應有隨從四身,一身爲彈琵琶、一身爲手持蓮花,由於畫面下端已損,無法確認另外二身。此東方琉璃光淨土因右側邊緣的“九橫死”(參見圖9-14,9-15,Fig.28)、左側邊緣的“藥師十二大願”(參見Fig.27)的故事畫而得以完整的體現。原本“藥師十二大願” 的想象空間沒有“九橫死”豐富,然而任何一幅藥師淨土圖中,所有“九橫死”都和觀音救助危難時的風格極其相似,所以藥師如來特性的形成深受觀音及其主尊阿彌陀如來的影響是顯而易見的。此繪畫與榆林窟第25窟南壁已經被確認為中唐的特別優秀的阿彌陀淨土圖非常相似(參見《文物》1956年第10期11~13頁),不僅諸尊的佈局和風格,而且諸如樹、鳥等細部的刻畫也極其相似。之所以要特別舉出這一點,是因爲從敦煌及其附近的美術品中,主要畫面的表現方式已趨保守並有延續,而在微細的部分,則有充分的餘地以便畫家發揮自己的經驗、觀察力及想象力。如此,舉個例子,我們特別觀察一下兩端的二層樓閣(參見圖9-5,9-6)。無論是這幅絹畫還是榆林窟的阿彌陀淨土圖,樓閣兩側均植有樹木,幾叢茂密的樹葉遮住了下层楼的屋頂。這些樹木的處理方式承襲了南北朝就已經固定了的風格,樹幹離地很近開出兩叉,粗枝中間有殘枝。樓閣一層內,細心製作的木結構須彌壇幾乎填滿了一間房子,上面放置着無人乘坐的蓮花座。上層的簾子,兩幅畫中都是有些卷起,有些垂下。絹畫左側的樓閣中可以见到朝外看的乾闥婆或者天女可愛的身影,其背後另有一位正在卷簾,頭和肩遮隐在簾後。將目光平移到右邊樓閣,則可以看到從建築物後面側身探出同樣的像,而另一個則坐在勾欄上兩手扶著,身子向前傾斜,以保持平衡。在壁畫中也能見到大致類似的情景(參見羅寄梅檔案No.3005,3006)。這些足以說明說明畫家細部写實的細致入微的觀察力和三維空間的刻畫已經達到爐火純青的程度。第25窟壁画的阿彌陀淨土圖中,阿彌陀三尊左右的寶臺上出現迦陵頻伽和大鳥各一組,每一組都展翅欲飛。鳥非常像天鹅,白色,右邊的鳥居然有奇妙的孔雀尾。而在此絹繪图中(圖9-1),這個位置則被多尊聖像占滿。迦陵頻伽的羽毛是條紋形,尾巴似波狀雲,位置則被挪到舞伎的前邊(參見圖9-3)。另外,天鵝一樣的大白鳥,其中一隻(右邊)已損壞,只留有像孔雀尾的站立在前景蓮池中的金沙島上(參見圖9-4)。在壁畫里,有鸚鵡飛落在畫面前方的勾欄上。敦煌絹畫中主要建築雖不如敦煌壁畫中的建築壯觀,如第172窟壁畫中的淨土圖(參見《敦煌壁畫》圖第144)。不過,如來正後方門樓的屋頂,則清楚地見到三組斗栱中有二層昂,細細觀察則發現兩角斗栱也有三層的昂,連圓檁子的頂端都表現得很清楚。柱間蜀柱最初看到的是兩個相對的尾飾葉紋的“S”形而不是帶有古風的倒“V”字形。不過,它還沒有被五臺山佛光寺9世紀大殿中所見的跳出更深的斗栱所取代。此處繪的是門樓的單層屋頂。其正上方所見的淡紅色的軒,顯然是一個獨立建築物的底層。那建築物是圍繞著勾欄的二層樓閣,因爲這部分畫面大幅破損,只能看見一角。可看到其屋頂與門樓有同樣的斗栱組合,屋頂上見不到昂。從門延伸出的長廊,繞過兩翼樓閣的背後,一邊明顯通到中堂,另一邊則延伸到左右的鼓樓和鐘樓的後邊,體現出庭院的開闊。白色的內壁,綠色的窗戶,青色的地板,院落邊緣及水池四周貼磚。四身菩薩分別踏立於蓮花座上。更生動的是,在高高聳起的建築物、華蓋上面,有身著長衣的飛天在空中起舞,拖着長長的飄帶,在層層疊疊的屋頂間和華蓋中忽隱忽現。通常的白牆赤柱沒有變化,但爲了清楚區分屋頂,青色屋頂的邊緣採用綠色,綠色屋頂的邊緣採用青色,相互交替搭配。再看邊緣部分,與壁畫有很強的的相似性,场景的刻畫都是直接取自現實的日常生活。我們可以用萬佛峽第25窟北壁彌勒淨土圖的宴會場面(參見羅寄梅檔案No.3020)做個例子,此繪畫右側邊緣的牽著獵犬的鷹獵者—— “打獵、競技、婦人、酒等,心力被鬼神所奪” (參見圖9-14,“橫死第三”)——富于表情的臨終時的場面、比丘和世俗男子好像在誦讀黃色經卷《藥師經》、病人臥在炕上被妻子攙扶著等場景,都栩栩如生,觀察的細致入微,是當時生活的真實寫照。至于山水,如壁畫上方右角半空中突起的懸崖(參見No.3006)和斯坦因繪畫36右側邊緣男子跳下的懸崖(參見圖9-15)等處,均可看出類似的地方。繪畫右側邊緣上端峻峭山谷前的樹木覆蓋的島嶼,是用墨色的線和晕染描繪的,與第25窟彌勒淨土圖(參見《敦煌飛天》圖74)上端所描繪的山水圖相同。此繪畫和榆林窟壁畫如此相似,說明藥師淨土圖是仿照阿彌陀淨土圖的同时,也為正在探討的佛教美術的題材是如何迅速傳播與使用的问题提供了生動的资料。因為我們必須假定是敦煌粉本傳到萬佛峽作爲那裏畫家的底本,或者是敦煌畫家親赴那裏從事壁畫製作的。前面已經討論過尺幅相當的兩幅繪畫(參見圖7,8),這幅畫則更大。它是用三幅幅寬爲56cm左右的絹子组成,整個畫面的幅寬比上面兩個作品寬約1.5倍。這可能是敦煌所製作的絹畫中最大的作品。與其大小大致相同的作品還有圖15、16、18和19,沒有將新德里國立博物館和集美博物館的作品列在裏面。邊緣故事圖的幅寬僅略大於圖8,所以中間部位極其寬闊,作者在那裏畫入衆多圍繞主尊的聖衆,還給整個畫面配上了雄偉的建築物。另外,此畫的上下四角還配有四尊密教萬神殿的神祗,使整個畫面具有曼陀羅式的氛圍(參見圖9-5,9-6,Figs.25,26)。最後,關于此畫的年代。盡管該畫与9世紀初淨土變密切相關(諸如圖8、11),實際上這幅畫可能在9世紀稍後的時期內。如果不與壁畫進行詳細比較,則無法判断出正確的年代。觀察山水的細部,樹木、枝葉已經開始形式化,描繪蓮池的勾欄上优雅地纏着的白色綬帶的线条,顯出僵化的苗頭,使我們感覺到,這是吐蕃時期敦煌与世隔绝後,已經公式化了的現象。注迦陵頻伽:在梵文《佛說阿彌陀經》,為一組鳥:鵝、麻鷸、孔雀、鸚鵡、八哥、杜鵑,鳩摩羅什譯為:白鵠、孔雀、鸚鵡、舍利、迦陵頻伽、共命之鳥(一鳥二頭)。在敦煌淨土畫中,天鵝、孔雀、鸚鵡非常容易識別。迦陵頻伽,在印度是一種妙聲鳥,有鳥的翅膀和腿,波浪狀的尾巴。共命之鳥,表現為兩個人頭的鳥,可參看Fig.38(《大正藏》,卷12,no.366,p.247a)。 Zwalf 1985The Buddha of Healing, a latecomer to the Buddhist pantheon, with his Eastern Paradise, enjoyed great popularity at Dunhuang. This large painting is the equivalent of some of the most complex and even larger paradise scenes on Dunhuang cave walls and is laid out like a depiction of Sukhāvatī, the Western Pure Land. Around the Buddha six figures make offerings. The Bodhisattvas Sunlight and Moonlight are surrounded by figures including the four Lokapālas and two demons. Above, on layers of red and blue clouds, appear Avalokiteśvara with 1,000 hands and Mañjuśrī with 1,000 bowls. The Eastern Paradise is completed by side scenes – the Nine Forms of Violent Death (right) and the Twelve Vows of Bhaiṣajyaguru (left). These side scenes and the twelve ‘yakṣa’ warriors in two groups on side terraces in the foreground distinguish the paradise of the Buddha of Healing from the Western Paradise of Amitābha on which it is closely modelled.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END

![[Qing Dynasty] British female painter—Elizabeth Keith, using woodblock prints to record China from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China—1915-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/image-191x300.png)