Period:Unknown Production date:1522-1567 (bowl)

Materials:porcelain, gold, silver,

Technique:glazed, gilded, cast, relief, mould-made, engraved, kinrande,

Dimensions:Diameter: 12.34 centimetres (dia. of bowl) Diameter: 8.10 centimetres (dia. of gold base) Height: 11 centimetres (incl. gold mount) Height: 5.30 centimetres (without gold mount)

Description:

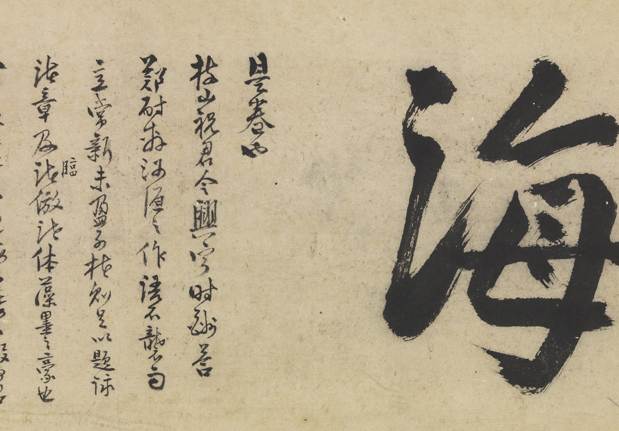

Bowl of Chinese green Kinrande porcelain, covered with a bright apple-green glaze outside, on which are floral arabesques with formal flowers in thin gold leaf: the inside undecorated. Mark in blue, imitating a pierced Chinese coin. The mount is of silver gilt and engraved; a narrow band encircles the edge, and is connected with the base by four hinged ribs. The foot is of unusual design; the upper member is a drum with an edging of lozenges cast in relief, resting on a fringe of egg-and-tongue pattern; then a deep and wide cavetto and below, a simple round moulding, engraved with a double band of neat linear scrolls, interrupted by ovals containing single letters.

IMG

![图片[1]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00141465_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_01155338_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7774.jpg)

![图片[3]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7774.jpg)

![图片[5]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7763.jpg)

Comments:Text from Read and Tonnochy 1928, ‘Catalogue of Silver Plate’ (Franks Bequest): The neatness and restraint displayed in the silver mount of this piece recall rather French than German work; but the initials suggest a ‘Graf von P.’The bowl is identical with one in the Franks Collection of Chinese porcelain having the same mark, and the tint of green and gold decoration is the same as that of a second bowl, bearing the mark of the period Chia-ching (1522-67) (‘Guide to the Pottery and Porcelain of the Far East’, 1924, P. 55, fig. 62), in a leather case of the sixteenth century.Compare blue kinrande bowl in MMA with German silver-gilt mount and red kinrande bowl in V&A, both illustrated in Levenson 2007, pp. 134-5 with this one. Harrison-Hall 2001:This mounted bowl is said to have come from a castle of the Grand Duke of Baden, Germany, where the silver-gilt mounts were applied in the second half of the sixteenth century. C. Hercules Read suggests that the initials G.V.P. may stand for Graf von P. Several other examples of Ming ‘kinrande’ bowls survive with sixteenth-century German mounts, including a blue ‘kinrande’ bowl with two silver-gilt sea-horse or dragon handles in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and a red ‘kinrande’ bowl in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, which according to a contemporary incised inscription was brought from Turkey to Germany by Count Eberhart von Manderscheidt in 1583 and mounted there on a silver-gilt pedestal. Both bowls were sold by the Eberhart family at Sotheby’s in 1970.In northern Europe during the second half of the sixteenth century, before the Dutch and English East India Companies escalated the scale of the ceramics trade and blue-and-white wares became de rigueur as ornament and tableware for most well-to-do households, Chinese porcelains were a luxury commodity whose ownership was confined to royalty and a few aristocratic families. Their rarity and romantic associations then may be compared to those of other exotic treasures such as ostrich eggs. In Tudor England, as well as in Germany during that period, silver-gilt mounts were added to Chinese porcelains which, with their dated hallmarks and associated documentation – wills, inventories and letters – provide vital information on contemporary attitudes to Chinese porcelain and its collecting history.

Materials:porcelain, gold, silver,

Technique:glazed, gilded, cast, relief, mould-made, engraved, kinrande,

Dimensions:Diameter: 12.34 centimetres (dia. of bowl) Diameter: 8.10 centimetres (dia. of gold base) Height: 11 centimetres (incl. gold mount) Height: 5.30 centimetres (without gold mount)

Description:

Bowl of Chinese green Kinrande porcelain, covered with a bright apple-green glaze outside, on which are floral arabesques with formal flowers in thin gold leaf: the inside undecorated. Mark in blue, imitating a pierced Chinese coin. The mount is of silver gilt and engraved; a narrow band encircles the edge, and is connected with the base by four hinged ribs. The foot is of unusual design; the upper member is a drum with an edging of lozenges cast in relief, resting on a fringe of egg-and-tongue pattern; then a deep and wide cavetto and below, a simple round moulding, engraved with a double band of neat linear scrolls, interrupted by ovals containing single letters.

IMG

![图片[1]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00141465_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_01155338_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7774.jpg)

![图片[3]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7774.jpg)

![图片[5]-bowl BM-AF.3130-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_DSC_7763.jpg)

Comments:Text from Read and Tonnochy 1928, ‘Catalogue of Silver Plate’ (Franks Bequest): The neatness and restraint displayed in the silver mount of this piece recall rather French than German work; but the initials suggest a ‘Graf von P.’The bowl is identical with one in the Franks Collection of Chinese porcelain having the same mark, and the tint of green and gold decoration is the same as that of a second bowl, bearing the mark of the period Chia-ching (1522-67) (‘Guide to the Pottery and Porcelain of the Far East’, 1924, P. 55, fig. 62), in a leather case of the sixteenth century.Compare blue kinrande bowl in MMA with German silver-gilt mount and red kinrande bowl in V&A, both illustrated in Levenson 2007, pp. 134-5 with this one. Harrison-Hall 2001:This mounted bowl is said to have come from a castle of the Grand Duke of Baden, Germany, where the silver-gilt mounts were applied in the second half of the sixteenth century. C. Hercules Read suggests that the initials G.V.P. may stand for Graf von P. Several other examples of Ming ‘kinrande’ bowls survive with sixteenth-century German mounts, including a blue ‘kinrande’ bowl with two silver-gilt sea-horse or dragon handles in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and a red ‘kinrande’ bowl in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, which according to a contemporary incised inscription was brought from Turkey to Germany by Count Eberhart von Manderscheidt in 1583 and mounted there on a silver-gilt pedestal. Both bowls were sold by the Eberhart family at Sotheby’s in 1970.In northern Europe during the second half of the sixteenth century, before the Dutch and English East India Companies escalated the scale of the ceramics trade and blue-and-white wares became de rigueur as ornament and tableware for most well-to-do households, Chinese porcelains were a luxury commodity whose ownership was confined to royalty and a few aristocratic families. Their rarity and romantic associations then may be compared to those of other exotic treasures such as ostrich eggs. In Tudor England, as well as in Germany during that period, silver-gilt mounts were added to Chinese porcelains which, with their dated hallmarks and associated documentation – wills, inventories and letters – provide vital information on contemporary attitudes to Chinese porcelain and its collecting history.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END