Period:Tang dynasty Production date:8thC

Materials:silk, hemp, 絲綢 (Chinese), 麻 (Chinese),

Technique:embroidered, woven, 刺繡 (Chinese), 織造 (Chinese),

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva monk/nun mammal apsaras canopy 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 供養人 (Chinese) 哺乳動物 (Chinese) 飛天 (Chinese) 華蓋 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 250 centimetres (Textile on board) Height: 241 centimetres Width: 167.50 centimetres (Textile on board) Width: 159 centimetres Depth: 2.80 centimetres (Textile on board, including old mount fixing)

Description:

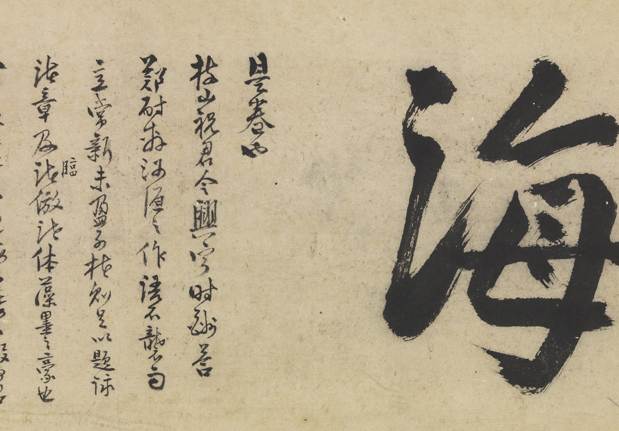

Embroidery executed in split stitch with the embroidery worked through the plain weave and the backing of hemp. The composition consists of a central Buddha figure beneath a blue canopy, flanked by two disciples and two Bodhisattvas on each side. Below are a number of donors. Inscribed.

IMG

![图片[1]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00031166_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00008410_002.jpg)

![图片[3]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00155805_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00155806_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155808_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155809_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155811_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00325537_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_face.jpg)

![图片[10]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_detail.jpg)

![图片[11]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front_whole.jpg)

![图片[12]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back_whole.jpg)

![图片[13]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__a_.jpg)

![图片[14]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__b_.jpg)

![图片[15]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__c_.jpg)

![图片[16]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__d_.jpg)

![图片[17]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__e_.jpg)

![图片[18]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__f_.jpg)

![图片[19]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__g_.jpg)

![图片[20]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__h_.jpg)

![图片[21]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__i_.jpg)

![图片[22]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__j_.jpg)

![图片[23]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__k_.jpg)

![图片[24]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__l_.jpg)

![图片[25]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__1_.jpg)

![图片[26]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__2_.jpg)

![图片[27]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__3_.jpg)

![图片[28]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__4_.jpg)

![图片[29]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__5_.jpg)

![图片[30]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__6_.jpg)

![图片[31]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__7_.jpg)

![图片[32]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__8_.jpg)

![图片[33]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__9_.jpg)

![图片[34]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__10_.jpg)

![图片[35]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__11_.jpg)

![图片[36]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__12_.jpg)

![图片[37]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__13_.jpg)

![图片[38]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_overall.jpg)

![图片[39]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Bottom_Right.jpg)

![图片[40]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Left_Group.jpg)

![图片[41]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Left_Group_Lion.jpg)

![图片[42]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Group.jpg)

![图片[43]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Lwr_Knot.jpg)

![图片[44]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Lwr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[45]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Feet.jpg)

![图片[46]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Top_Head.jpg)

![图片[47]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Torso.jpg)

![图片[48]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Ctrl_Btm_Feet.jpg)

![图片[49]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Ctrl_Btm_Panel.jpg)

![图片[50]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Lwr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[51]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Mid_Torso.jpg)

![图片[52]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Top_Corner.jpg)

![图片[53]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Upper_Torso.jpg)

![图片[54]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Mid_Rt_Upr_Torso_Head.jpg)

![图片[55]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Mid_Rt_Upr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[56]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre___Hair.jpg)

![图片[57]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre_Head___Hand.jpg)

![图片[58]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre.jpg)

![图片[59]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Rt_Group.jpg)

Comments:The embroidery with the motif of Sakyamuni preaching on the Vulture Peak is a magnificent work executed in split stitch with the embroidery worked through the plain weave and the backing of hemp. Most of the stitches are long, around 0.8-1 cm, and split stitches of this sort are similar to satin stitches, perhaps representing a transitional stage between split stitch and satin stitch.The composition of the embroidery consists of a central Buddha figure beneath a blue canopy, flanked by two disciples and two Bodhisattvas on each side. Below are a number of donors. The Buddha stands on a lotus pedestal with his right shoulder uncovered and his right hand extended straight down, while his left holds the hem of his robe, which is the usual posture for Sakyamuni on this occasion. His body is enclosed, to its full height, within an almond-shaped aureole that reaches to just above the nimbus around his head. Behind the mandorla is a rocky surround, representing the Vulture Peak. At the top of the hanging, on either side of the canopy are apsaras and two lions crouch on either side of the lotus pedestal.The kneeling donors at the bottom of the hanging are divided into two groups. There are five men at the lower right: one monk, three men wearing modest caps decorated with ribbons which fall down the men’s backs and a male servant stands behind them. At the lower left are four seated ladies in high-waisted dresses and shawls or jackets with half sleeves. There is also a small boy beside one lady and a maid standing behind. Most of the embroidered Chinese characters next to the donors can no longer be identified. The central figure of Sakyamuni has escaped damage altogether, while the two Bodhisattvas have suffered only slight damage. The two disciples, partly hidden behind the Bodhisattvas, have suffered the most.Inscribed.巨型刺繡畫,長方形,表現的是釋迦牟尼在靈鷲山說法的場景。爲使刺繡牢固,使用了兩層繡地——本色絹背襯以本色麻布。繡品中主要使用了自北朝自盛唐間十分流行的劈針針法,但大多數針腳較長,約在0.8-1.0cm左右,應該是介於劈針和平針之間的過渡期。因此,這件繡品的年代不會太晚。繡品中心是釋迦牟尼的形象,他站在斑駁的岩石之前,這些岩石代表的正是靈鷲山。釋迦牟尼身披紅色袈裟,坦露右肩,赤腳立於蓮座之上,蓮座兩側各有一白色獅子,他的身後有背光和頭光裝飾,右手筆直指向地面,左手在胸前提起袈裟,這是在這類場景中經常出現的姿勢。其頭部上方則是一藍色華蓋,華蓋兩側各有一飛天形象。釋迦牟尼兩側各有一佛弟子和菩薩,均是赤腳立於蓮座之上的形象,菩薩基本上完整地保留了下來,但佛弟子除了頭部之外,身體的其餘部分均已缺失。繡品的右下方跪著四個男供養人,其中一人爲和尚裝扮,另外三人則均頭戴黑色襆頭,身穿藍色圓領袍,身後是一個站立的男性侍者;左下方是則跪有四個女供養人,頭梳髮髻,身穿窄繡襦,外罩半臂,身系各色長裙,有的披有披帛,一婦女身旁還跪有一男童,他的尺寸特別小,她們身後站立著一個身穿袍服的侍女。供養人身旁的題記上繡有“義明供養”、“一心供養”等字,但多已湮滅不可辨認。刺繡佛像在唐代十分常見,而且在敦煌文書中也經常可以看到。P.3432《龍興寺卿趙石老腳下依蕃籍所附佛像供養具並經目録等數點檢曆》中載有:“繡像壹片,方圓伍尺”;“繡阿彌陀像壹,長三箭,闊兩箭,帶色絹”。唐時一尺約爲30cm,吐蕃時期的一箭約等於50cm,即前一件繡像約方圓150cm,後一件繡阿彌陀佛像長150cm、寬100cm,比此件小。技術分析:組織結構: a. 本色絹經線:絲,無撚,單根排列,本色,30根/cm;緯線:絲,無撚,單根排列,本色,21根/cm;組織:1/1平紋。b. 本色麻布經線:絲,S撚,單根排列,本色,11根/cm;緯線:絲,S撚,單根排列,本色,8根/cm;組織:1/1平紋。刺繡: 繡線:絲,一般爲兩根Z撚以S撚併合;色彩:白、紅、黑、深藍、淺藍、褐、黃、土黃、綠、淺綠、棕等。針法:劈針等。 EnglishFrom Whitfield 1985:This is one of the most magnificent of all the compositions found in the hidden library at Dunhuang. As an embroidery it may rank with the Shaka Nyōrai Preaching, of similar size (207×157cm) and also of the eighth century, from the Kanshū-in, now in the Nara National Museum (see Nihon bukkyō bijutsu no genryū, p.254). Other items of embroidery in the Stein Collection at the British Museum are of a decorative character, but this work must have been equal in importance to the finest and largest of the paradise paintings on silk. The composition consists of a five-figured Buddha group, over which appears a canopy with apsarasas, and below are a number of donors. The Buddha stands on a lotus pedestal, beneath the blue canopy. His body is enclosed, to its full height, within an almond-shaped aureole that reaches to just above the nimbus around his head. Behind the mandorla is a rocky surround, representing Mt.Grdhrakūta, or the Vulture Peak, at Rājagrha, the scene of the preaching of the Lotus Sutra. The Buddha stands with his right shoulder uncovered and his right hand extended straight down, while his left grasps the hem of his robe, in the usual posture for Sākyamuni on this occasion (see also Vol.1, Pl.22). By good fortune and through the care with which the whole embroidery was folded, the central figure of Sākyamuni has escaped damage altogether, while the two Bodhisattvas have suffered only slight losses. It is the two disciples, already partly hidden behind the Bodhisattvas, who have been damaged the worst: as Stein noted in Serindia (Vol.Ⅱ, p.983), these figures fell along the line of folding when the hanging was put away, “and have for the most part been eaten away. ”Enough of the two figures survives, however, to reveal their individual characters and to show that their robes originally just touched the outermost contours of the rocky cliff. The two Bodhisattvas are almost completely visible. They and the disciples stand on lotus pedestals and seen in three-quarter view. As they are placed just in front of and a little below the disciples, the effect of the whole composition is to form a space enclosing the central Buddha, echoing the arrangement that would have been found if the group had been a sculptural one. This feeling for space and volume, despite the medium of embroidery in which it must have been especially difficult to achieve, is in itself powerful evidence of a date of execution early in the Tang dynasty when such concerns are characteristic of both sculpture and painting. That there were sculptural models for Sākyamuni on the Vulture Peak, though distant in time and space, is suggested by the presence of this representation in the New Delhi section of the painting of Famous Buddhist Images (see Vol.2, text figure, p.306), where Sākyamuni appears alone, against a rocky background. In that painting, several features indicate that the figure of Sākyamuni reflects, although not at first hand, a sculpture in stone. Like many of the other figures in the Famous Buddhist Images painting, this one is not coloured, but simply represented in ink outline. The mandorla enclosing the figure is straight at the sides and semicircular at the top, where it completely encloses the nimbus; its form and the small seated Buddha visible above Sākyamuni’s right shoulder strongly suggest that the original model was a free-standing stone stele. Only beyond its confines are there long coloured flames, and outside these the rocky forms of the Vulture Peak shaded in ink and some of them coloured. This seems appropriate in a painting which was primarily a record of famous images. Among the wall paintings at Dunhuang, the Sākyamuni Preaching on the Vulture Peak, in Cave 332, datable to the early Tang (Chūgoku Sekkutsu, Tonkō Makkōkutsu, Vol.3, Pl.88) is close to the embroidery in scale and composition. The scene is painted on the north face of the pillar behind the main images, in the corridor at the back of the cave. Sākyamuni, clad in a red robe, stands between two Bodhisattvas, Avalokitesvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta. His nimbus and mandorla have a broad edging of flames, and the outlines of cliffs and mountain peaks appear behind. There are no disciples, and three canopies rather than one complete the composition. The colours in the wall painting have suffered a good deal of abrasion and loss, so that a detailed comparison is not possible. As a general impression, however, the figure of Sākyamuni appears somewhat stiffer, the robe pulled up tightly under the right arm, crossing the chest almost horizontally rather than falling gracefully in a single curve from the left shoulder. In both figures the edges of the outer garment are seen to wave (revealing a lining of a different colour) across the chest, around the shoulder and upper left arm and as two wavy edges falling from the gathering in the Buddha’s left hand. The more schematic character of the wall painting can be judged in this last fall, since the waves are juxtaposed and mirror each other exactly, while in the embroidery each pursues its own rhythm, and the differences in the undulations help to reveal the shape of the figure. The schematic character of the wall painting is on the whole closer to the depiction of Sākyamuni in the Famous Buddhist Images painting than to the embroidery: note especially the way in which the upper edge of the robe is brought up close under the right arm, and the stiff waves of the edges of the robe. The same double lines are used, however, in both the silk painting and the embroidery to indicate drapery folds, so all three depictions have points in common. In the embroidery, frequent slight variations in colour enhance the liveliness already present in the initial outlines-each fold is narrowly outlined in blue, always following the underdrawing in ink, which is visible in every place where the threads are broken or missing. Turning to the depiction of the facial features in the several figures of this embroidery, we can observe subtle variations here also. The elderly disciple on Buddha’s left has the most vigorous appearance, with blue outlines strongly accenting all the main lines and even outlining his teeth, and used in a regular vertical crosshatching of the eyebrow, indicated on the silk ground beneath by an area of ink wash. The iris of his eye is painted in black ink directly on the silk ground without any overlying embroidery. Of the face of his companion opposite, enough remains to show that he had smooth features: the iris is again rendered in black ink on the silk ground, but the eyebrow above is embroidered with long thin stitches of blue interspersed with others of the pale silvery silk used for the rest of the head, so that the eyebrow appears smooth and delicate. In the Bodhisattvas, the eyebrows are indicated by single blue arcs as are the inner upper edge of the orbit and the almond-shaped contour of the eye. The iris is painted in ink, not on the silk ground beneath, but on the embroidery. The nose is outlined with a single line of stitches once perhaps tinged with red but now faded to a very pale yellow, as have the lips. Even greater care was taken with the countenance of the Buddha. His hair is of the deepest indigo, edged in the lighter blue that also outlines the face and models the ears. In the centre of the hair at the base of the usnisa, this same lighter blue frames a small circle of the exposed white silk ground representing a jewel. The slender, finely arched eyebrows are in a lighter shade than the indigo used for the hair. The eyes, outlined in blue, are filled with horizontal rows of chain stitch in a whiter silk than the rest of the face: against this the irises, painted in black ink directly on the silk ground, stand out clearly and indeed seem have been lightly padded from behind so as to appear slightly raised. The edges of the eye orbit, the whole of the nose, the mouth, complemented by associated modelling lines and chin line. Are all in a golden colour. For the rest of the face, the rows of stitches follow both the outer contours and the inner features, thus revealing the whole circle of the orbit merely through the arrangement of the stitches. The dramatic effect of the modelling must originally have been much strengthened by differences of colour: today many of these colours have greatly faded, while the blues of the indigo have remained strong since they were initially created by oxidation. Although these subtleties only reveal themselves on close examination, they do account for the extraordinary presence of the figures, and testify to the early date of the whole composition. Only in the early and high Tang do we find such close and constant attention to details that constantly serve to enhance the movement and form of the figures. Details such as the hands of the two Bodhisattvas show great sensitivity: those of the Bodhisattva on Buddha’s right are in anjalimudrā, palms pressed together, but with the index of right hand just crooked behind the rest. On Buddha’s left, the Bodhisattva’s right hand is extended, palm outwards; the thumb is missing but the wrist is intact and completely relaxed. Wrist and fingers are again seen to perfection in the left hand: no opportunity to depict graceful movement has been lost. In all these details the embroidery has followed the original cartoon in ink, which set out even such minor details as the flowers and buds scattered by the heavenly beings above. It invites comparison with the most delicate of the early Tang wall paintings, such as the Bodhisattva as Guide of Souls in Cave 205(Vol.2, text figure, p.302), or a donor in Cave 401(Chūgoku Sekkutsu, Tonkō Makkōkutsu, Vol.3, Pl.7). Such comparisons inviting an early date are confirmed when we examine the demure attitudes of the donors below: the ladies in high-waisted dresses, with shoulder shawls: the men with modest cap-ribbons falling naturally; while at the top the canopy is of the domed kind, with curved ribs and segments alternating in colour, that we have already seen in the Representations of Famous Buddhist Images(Vol.2, Fig.9). As noted above, the panel, apart from the losses sustained through long storage in a folded state, is in an amazingly good state of repair. The edges on both sides have been well preserved, and very little, if any, of the top and bottom edges has been lost, other than perhaps a few centimetres of unembroidered space. The panel is made up of hemp cloth, now visible in many place, although this was originally entirely covered by thin silk of a balanced close weave. Although this silk has now largely perished, it can still be seen easily, particularly in the upper left corner. Both the thin silk ground and the hemp cloth support are in fact formed of three widths of material sewn together, the seams being completely hidden when beneath the embroidery, but now easily visible on the plain ground due to the better preservation of the silk along the edges of the seams. After the embroidery reached London, it was couched on a new linen backing and mounted on a stretcher as a panel. For many years it hung in a glazed frame on the landing of the North Staircase of the British Museum, protected by a curtain. When the upstairs galleries were renovated in 1971, a special case was prepared for it so that it is frequently on view at entrance to Oriental Gallery Ⅱ. Close examination of the embroidery shows that the design was first drawn in outline in ink directly onto the silk ground. Following this preliminary drawing, the main contours were first worked, most of them in dark blue silk, in lines of split stitch. In some places, for example in the contours of the rock of the mountain and in some of the drapery of the Bodhisattva on the left, these outlines were done in brown instead of blue. After this each of the areas enclosed by the outlines was filled by closely packed soft unplied floss silk. Stein describes this as “worked solid in satin stitch, ”but it many perhaps be split stitch, with long over-lapping stitches to produce a satiny finish. In general these lines fill the area in the same way that a field many be ploughed, following the outer boundaries and gradually reducing the area left to be done. There are , however, a number of variations: in many places the outlines are dispensed with and, just as in kesi (kossu; 緙絹) weave, a consistent division produces a line within a single colour, as in the centre line of the breast of the Bodhisattva on the right. This technique is also used in conjunction with a change of colour, for instance on the breast of the Buddha himself; it is used again to mark the edges of the petals in the lotus pedestals, and of the floral motifs in the embroidered hems of the garments of the two Bodhisattvas. The rock structure of the Vulture Peak, in several colours, is distinguished both by outlines in blue or brown, and occasionally by setting the filling stitches at right angles in adjacent facets of the rock, giving a sharp variation in reflectance. Within each area so filled, there are subtle variations in colour, as well as differences in the length of stitch and type of silk used. For most of the large areas, the silk used is a single, rather full, unplied floss silk, and the stitches are long, often between 8 and 10 mm in length, giving a satiny appearance. In many places, however, as it was worked behind the needle, the two strands of the silk lightly twisted together (within each strand the silk is of course untwisted): this can be seen for example in the blue rock. In places where the silk is finer, this twisting of the strands is correspondingly tighter, as can be seen in some areas of the Bodhisattvas’ robes. Sometimes the stitches were much shorter in order to give a different surface texture. The clearest example of this is in the stitch (still a split stitch but with short stitches instead of long ones) used for the Buddha’s extended right arm. Here a totally different effect is achieved since each line of split stitch, instead of being closely packed, is quite separate from its neighbours, leaving the underlying thin silk ground clearly visible. When the embroidery was new, this technique must have resulted in an enhanced luminosity of the forearm and hand, distinct from the golden colour of the upper arm and shoulder; indeed this is still true today. In the hand itself, the way in which the lines of stitches follow the curves of the fleshy parts of the palm and fingers can be seen directly in the plate (Pl.1-2). The outlines of this hand and of the arm right up to the shoulder are in a silk which today appears completely black, without a hint of blue. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1985:這幅刺繡作品色彩豐富,技藝精湛,是敦煌藏經洞出土的最優秀的作品之一。從刺繡的做工上說,可與奈良國立博物館藏(勸修寺舊藏)的《釋迦牟尼說法圖繡帳》 (見《日本佛教美術源流》,254頁)相媲美(該作品製作於8世紀,尺寸爲207×157cm)。大英博物館所藏的斯坦因收集品中,還有其他一些刺繡作品,但多是裝飾性的,而該作品則同其他絹繪淨土圖一樣氣勢壯觀。此圖由五尊佛像構成,上部是華蓋和飛天,下部是衆多的供養人像。佛陀站立在青色華蓋遮敝的蓮華寶座上,扁桃形的身光環繞著身體與頭光等高。曼陀羅的背後有一座岩山,可以想見,這是《法華經》中所說的靈鷲山。佛陀偏袒右肩,右手垂直下放,左手執衣襟。這是所有靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖中所共有的一種姿勢(參見卷1,圖22)。該刺繡曾長期疊放在藏經洞中,所以兩尊菩薩的像有部分破損,幸運的是主尊釋迦牟尼保存完好,菩薩略有殘損,而破損最嚴重的是兩尊菩薩背後只露出半個身子的兩尊弟子的像。造成這種破損的原因,正如斯坦因在《西域》(Serindia,卷2,983頁)中分析的那樣,是在人們取下畫上的吊繩折疊存放時,這些部位正好處在折線上。在斯坦因發現它時,這些像就已幾乎散失,但通過殘存部分仍能辨別出這二尊弟子的容貌,也能確認他們的衣物本是連在突兀的斷崖上的。二尊菩薩基本保存完好,和二尊弟子一樣,斜向前方站立在蓮華座上。他們緊挨弟子站在前方,在圖中的位置比弟子略低。主尊周圍各尊佛像的這種佈局,與我們在雕像中所見到的各尊佛像的陳列方式一樣,顯現出一定的空間進深。從技術上說,用刺繡是很難表現出空間感和量感的,但是這副作品卻實現了這一點。這一特點有力地証明了該作品的製作爲初唐時期。因為在初唐時期,無論是繪畫還是雕刻,人們都越來越注重表現空間感和量感。新德里國立博物館藏的《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》(參見卷2,解說插圖,306頁)中也有用岩山做背景的釋迦牟尼獨尊像。雖然兩幅作品産生的年代和地點相差很遠,但可以推測,過去確實存在有一座雕像,《靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖》中的釋迦牟尼就是依據這座雕像創作的。《瑞像圖》中的釋迦牟尼像雖然沒有直接摹寫石雕像,但在很多地方我們都能夠找到石雕像的影子。以岩山做背景的佛像,與其他諸像一樣,只使用墨線而無色彩。環繞佛像的背光,兩側爲豎立的直線,上端呈半圓形,項光被完全納入其中。這種背光的表現形式、釋迦牟尼右肩上方的小坐像,使人強烈地感到這幅作品是以石雕爲原型創作的。只有彩色的長長的火焰光越出了背光的界線,外側是墨線勾勒的彩色的靈鷲山岩石,這種表現手法正適合於該作品記錄瑞像的目的。在敦煌壁畫中,初唐時期建造的第332窟(《中國石窟•敦煌莫高窟》卷3,圖88)的壁畫裏,也有與此非常相似的《靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖》。該圖繪在洞內後方回廊部位的方柱北面,釋迦牟尼身裹紅色袈裟,兩側站立著觀音、勢至二尊菩薩。背光和項光附有寬大的火焰紋,背後用線描繪出了斷崖或山上裸露的岩石。畫中沒有弟子,只有三頂華蓋,而非完整構圖。壁畫的色彩漫漶、脫落嚴重,無法對細節部分進行比較和研究。然而,此壁畫給人的整體印象是,釋迦牟尼的像比較生硬,通常從左肩用柔和的弧線來描繪的衣服,在此用斜線幾乎橫切前胸,看似牢牢夾在右腋下方。外衣的邊緣呈波浪狀(能看到襯裏的不同顔色);外衣從胸前穿過,從肩繞至左上臂,集中到左手,再從左手處形成兩條紐帶垂落下來。這些細節與本圖中的佛像相同。比較雙方對最後紐帶部分的處理,可以看出壁畫相對顯得有些形式化。壁畫中,紐帶的波紋兩條兩條地整齊地並列在一起,而刺繡中二條紐帶則分別有著自己的運動節奏,呈現出不同的波浪起伏,這種處理方法有助於刻畫釋迦牟尼的形象。從整體上看,與本圖的刺繡作品相比,此幅壁畫的形式化的表現方法,更接近於《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》。特別是橫過前胸的衲衣上端被右腋牢牢夾住、衲衣邊緣的波浪起伏用直線生硬地勾畫,這些都很引人注目。而另一方面,絹繪的瑞像圖和本刺繡作品中,衣褶都用雙線表示,所以說三者之間存在共同點。刺繡作品中,僅有的幾種顔色變化頻繁,進一步增加了樣本已具有的生動感。袈裟則用藍色線沿著底稿的墨線細緻地刻畫,在那些絲線已斷裂、缺失的地方,我們還可以看到底稿的墨線。再看諸佛的面容,其表現也有一些細微的變化。表情最爲生動的,是站在如來左邊的年老弟子,包括牙齒的輪廓線在內,主要線條均用藍色突出出來。眉毛是在絹底上用淡墨畫的,粗粗的,上用線繡出一些細毛。黑眼珠是在絹底上直接用墨描繪的,沒用刺繡。右側弟子面部雖然只殘留一小部分,但能看出他表情柔和。黑眼珠也是在絹底上用墨點出的,眉毛則使用藍色線,針腳細而長。臉部到頭部使用淡銀色線,幾種顔色搭配在一起,顯得柔和、細膩。二菩薩的眉毛與眼窩線及杏核眼的輪廓,都使用了一根藍色的弧線來表示。而黑眼珠沒畫在絹底上,是用墨繪在了刺繡上。鼻梁線與嘴唇線使用了相同的顔色,當初可能是淡紅色,但現在已褪變爲黃色。佛陀的面容更是下了許多功夫。頭髮是深藏青色,臉部、耳朵的輪廓線都使用了明快的藍色。頭髮中央的肉髻珠的位置,留出了圓形的白色絹底,周圍圈以明快的藍色,看似寶石。細細的眉毛呈優美的弧形,顏色與頭髮的深藏青色相比有淡淡的陰影。眼睛輪廓爲藍色,眼白則用比臉部還白的絹絲,採用鎖繡的手法水平刺繡而成。而黑眼珠則是在絹底上直接用墨描繪。黑眼珠具有鮮明的立體感,其實是在下面墊了東西使其稍稍凸出來一點。眼窩、鼻、唇、下顎以及裸露的身體,均使用金黃色。面部其他部分則分別沿著臉的輪廓線和五官的輪廓線刺繡而成,看起來像是打著漩兒。裸露的身體當初肯定有著強烈的色彩變化,但現在,大部分已褪色,只有深藏青色還殘留著它的鮮豔。只有在對該作品進行仔細的研究之後,我們才能發現這些細節部分的精妙之處。這些細節不僅表現出其在佛像刻畫中的非凡之處,也證明了該作品本身的製作年代之早。因爲這種極其注重細節並以此提高佛像生動感的特色,只在初唐到盛唐間的作品中才能見得到。再看二尊菩薩的手,我們會發現對細節部分的刻畫幾乎到了細緻入微的地步。如,合掌侍立在釋迦牟尼右側的菩薩,右手食指彎曲,藏在其他手指的陰影裏。侍立在左側的菩薩,右手伸開,掌心向外,拇指雖已殘缺,但手腕處保存完好,並表現出了柔弱無力的樣子。其左手的手腕和手指完整地保留至今,仍然優雅生動。這種細節是沿著底稿上的墨線用刺繡來刻畫的。圖上方飛天周圍散落的花朵、花蕾等細節的刻畫方法也與此相同。綜上所述,和敦煌初唐時期的壁畫相比,該作品可以和第205窟西壁的《引路菩薩圖》(卷2,解說插圖,306頁)、第401窟的《供養菩薩圖》(《中國石窟•敦煌莫高窟》卷3,圖7)等最爲精緻的壁畫相媲美。可與這些早期作品相媲美的地方,還有對圖下部供養人像文雅姿態的刻畫:女供養人在齊胸的裙子外披肩巾、男供養人柔軟垂落的襆頭等。另外,圓頂華蓋是通過表現不同的材料的交互將顔色分開,在《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》(卷2,Fig.9)中也能見到這種表現方式。前面已經介紹過,由於此作品被長時間折疊存放,除殘損部分外,其餘部分保存完好得令人驚訝。畫面的兩端都完好無損,上下邊即使是保存下來,也不過是數釐米沒有刺繡圖案的絹底。此作品本來是在麻布上鋪了一層質地緻密的薄絹。薄絹已損壞相當嚴重,但畫面右上部的部分卻殘留了下來。整個作品是用三幅這種薄絹面和麻布裏重疊的布料縫合而成的,縫合的針眼本應是完全隱蔽在刺繡下面的,但現在,部分針眼在絹面上已經隨處可見。此繡品運送到倫敦以後,被重新用麻布裱褙,變得象幅油畫一樣,還加上了玻璃鏡框。在很長一段時間裏,覆蓋著幕布挂在大英博物館北部樓梯的平臺上。到了1971年,博物館二層陳列室改建時,才被放進特製的匣子裏,擺放在東方繪畫陳列室入口處顯眼的地方。仔細查看該作品,我們會發現其是先將底樣直接描繪在絹底上,然後照樣刺繡的。主線基本上是用深藏青色絲線割繡。但有一部分如裸露的山石、侍立右側的菩薩的袈裟等等,則用褐色取代了藏青色。然後用柔軟的單股絹絲認真填平用線圈起來的範圍,雖然斯坦因稱其爲緞繡,但從其長而平滑的針腳看,恐怕應是割繡。一般來說,用刺繡填埋輪廓線內的空白,就像耕地一樣,沿輪廓線來回做往復運動,逐漸縮小空白部分。但在這裏,不只是用這種方法,而是産生了各種變化。不僅運用直線針,更多則採用織錦似的針法,如侍立左側的菩薩胸部的中線,就是在同種色線繡出的部位中加上非常明顯的分界線。此種手法,除了使釋迦牟尼胸部顔色更具變化外,也使蓮華座的花瓣兒更醒目、二尊菩薩的衣邊兒花紋爲更突出。背景中岩石臨接的地方使用相互垂直的針腳,表現出了岩石表面的凹凸不平。在填埋各部分時,通過變換針腳的長短或所用絲線的種類來産生色彩的微妙變化。面積較大的部分則幾乎都是使用未撚的單股線,針腳有8-10mm,表面顯得很有光澤。但很多地方繡針在往返時使兩股線輕輕地撚在了一起(單股線不用撚)。這一特點在岩山的青色部分表現得非常明顯,而且在菩薩的衣裳上也是隨處可見,用細線繡的部分,線都撚在一起,非常細密。同時這些地方針腳較短,表面的感覺也略有不同。其中一個明顯的例子,就是釋迦牟尼伸向下方的右手,上下部分的繡法雖然相同,但針腳從上部到下部逐漸由長變短。並且,下部所繡的各線沒有緊密填補空間,針與針之間有距離,從隙間露出了薄絹底,産生出與上部完全不同的效果。與我們今天所看到的情形不同,這幅作品在剛完成時,前臂和手掌因這種技法而産生了與金色的肩部和上臂部不同的效果,其亮度要更大一些。這種效果現在還沒有完全消失,從手部擴大圖(圖1-2)上可以看到,刺繡的線沿著手掌及手指的曲線描繪出不同的弧度。現在,其手的前部及手腕到肩等處的輪廓線變成了黑色,已看不出原來的藍色了。 Zwalf 1985This splendid embroidery, as large as any Dunhuang paintings found by Stein, shows the Buddha in the rocky surround of the Vulture Peak (Ghṛdhrakūṭa) at Rājagṛha preaching the ‘Lotus Sūtra’. It had been carefully folded to protect the Buddha, but beneath the fold the two disciples representing the Hīnayāna are damaged. Celestial figures scatter flowers from above, and the donor family is ranged on either side below. The style and quality make this one of the finest Tang dynasty works. Rawson 1994:Rawson 1994:All types of textile art flourished during the Tang dynasty (AD 618-906) in China. An important group of Tang textiles has recently been found in excavations at the Famensi at Fufeng, in Shaanxi province; gifts to this monastery evidently included clothing as well as glass, silver and ceramics. Embroidery also continued to be developed and was used for large images of the Buddha built up in satin and chain stitch. Most of the textiles found by Aurel Stein at Dunhuang in Gansu province, including banners, altar hangings and monks’ apparel, follow the Buddhist convention of being made up of small cut pieces of different cloth. These ‘patchwork’ items provide an invaluable cross-section of the different types of silk cloth and embroidery available at the time (BM MAS.857).Trade along the Silk Route was at its most vigorous during the Tang dynasty, and travellers record the bazaars of the Middle East as being full of Chinese patterned cloth and embroideries. Simultaneously we are told that the Tang capital at Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) was populated by large numbers of Iranian craftsmen. A silk weave now known as “weft-faced compound twill” appears among Chinese textiles for a few centuries from about AD 700. This may well have been a technique introduced by foreign weavers, as it seems to have been developed originally in Iran. In the West it was particularly associated with repeating designs of roundels enclosing paired or single animals, with flower heads or rosettes between the roundels (BM MAS.876 and 877). The scroll design with flowers and birds occurs in ceramics and other decorative arts from the Tang dynasty onwards. The Getty’s curatorial team suggests the title as Miraculous Image of Liangzhou (Fanhe Buddha)

Materials:silk, hemp, 絲綢 (Chinese), 麻 (Chinese),

Technique:embroidered, woven, 刺繡 (Chinese), 織造 (Chinese),

Subjects:buddha bodhisattva monk/nun mammal apsaras canopy 佛 (Chinese) 菩薩 (Chinese) 和尚/尼姑 (Chinese) 供養人 (Chinese) 哺乳動物 (Chinese) 飛天 (Chinese) 華蓋 (Chinese)

Dimensions:Height: 250 centimetres (Textile on board) Height: 241 centimetres Width: 167.50 centimetres (Textile on board) Width: 159 centimetres Depth: 2.80 centimetres (Textile on board, including old mount fixing)

Description:

Embroidery executed in split stitch with the embroidery worked through the plain weave and the backing of hemp. The composition consists of a central Buddha figure beneath a blue canopy, flanked by two disciples and two Bodhisattvas on each side. Below are a number of donors. Inscribed.

IMG

![图片[1]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00031166_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00008410_002.jpg)

![图片[3]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00155805_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00155806_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155808_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155809_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/00155811_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_00325537_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_face.jpg)

![图片[10]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_detail.jpg)

![图片[11]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front_whole.jpg)

![图片[12]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back_whole.jpg)

![图片[13]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__a_.jpg)

![图片[14]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__b_.jpg)

![图片[15]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__c_.jpg)

![图片[16]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__d_.jpg)

![图片[17]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__e_.jpg)

![图片[18]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__f_.jpg)

![图片[19]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__g_.jpg)

![图片[20]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__h_.jpg)

![图片[21]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__i_.jpg)

![图片[22]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__j_.jpg)

![图片[23]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__k_.jpg)

![图片[24]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_front__l_.jpg)

![图片[25]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__1_.jpg)

![图片[26]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__2_.jpg)

![图片[27]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__3_.jpg)

![图片[28]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__4_.jpg)

![图片[29]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__5_.jpg)

![图片[30]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__6_.jpg)

![图片[31]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__7_.jpg)

![图片[32]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__8_.jpg)

![图片[33]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__9_.jpg)

![图片[34]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__10_.jpg)

![图片[35]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__11_.jpg)

![图片[36]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__12_.jpg)

![图片[37]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_back__13_.jpg)

![图片[38]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_overall.jpg)

![图片[39]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Bottom_Right.jpg)

![图片[40]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Left_Group.jpg)

![图片[41]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Left_Group_Lion.jpg)

![图片[42]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Group.jpg)

![图片[43]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Lwr_Knot.jpg)

![图片[44]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Btm_Rt_Lwr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[45]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Feet.jpg)

![图片[46]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Top_Head.jpg)

![图片[47]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Centre_Torso.jpg)

![图片[48]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Ctrl_Btm_Feet.jpg)

![图片[49]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Ctrl_Btm_Panel.jpg)

![图片[50]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Lwr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[51]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Mid_Torso.jpg)

![图片[52]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Top_Corner.jpg)

![图片[53]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Left_Upper_Torso.jpg)

![图片[54]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Mid_Rt_Upr_Torso_Head.jpg)

![图片[55]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Mid_Rt_Upr_Torso.jpg)

![图片[56]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre___Hair.jpg)

![图片[57]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre_Head___Hand.jpg)

![图片[58]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Centre.jpg)

![图片[59]-textile; 紡織品(Chinese) BM-MAS-0.1129-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Tang dynasty/43/mid_RFC32320_Top_Rt_Group.jpg)

Comments:The embroidery with the motif of Sakyamuni preaching on the Vulture Peak is a magnificent work executed in split stitch with the embroidery worked through the plain weave and the backing of hemp. Most of the stitches are long, around 0.8-1 cm, and split stitches of this sort are similar to satin stitches, perhaps representing a transitional stage between split stitch and satin stitch.The composition of the embroidery consists of a central Buddha figure beneath a blue canopy, flanked by two disciples and two Bodhisattvas on each side. Below are a number of donors. The Buddha stands on a lotus pedestal with his right shoulder uncovered and his right hand extended straight down, while his left holds the hem of his robe, which is the usual posture for Sakyamuni on this occasion. His body is enclosed, to its full height, within an almond-shaped aureole that reaches to just above the nimbus around his head. Behind the mandorla is a rocky surround, representing the Vulture Peak. At the top of the hanging, on either side of the canopy are apsaras and two lions crouch on either side of the lotus pedestal.The kneeling donors at the bottom of the hanging are divided into two groups. There are five men at the lower right: one monk, three men wearing modest caps decorated with ribbons which fall down the men’s backs and a male servant stands behind them. At the lower left are four seated ladies in high-waisted dresses and shawls or jackets with half sleeves. There is also a small boy beside one lady and a maid standing behind. Most of the embroidered Chinese characters next to the donors can no longer be identified. The central figure of Sakyamuni has escaped damage altogether, while the two Bodhisattvas have suffered only slight damage. The two disciples, partly hidden behind the Bodhisattvas, have suffered the most.Inscribed.巨型刺繡畫,長方形,表現的是釋迦牟尼在靈鷲山說法的場景。爲使刺繡牢固,使用了兩層繡地——本色絹背襯以本色麻布。繡品中主要使用了自北朝自盛唐間十分流行的劈針針法,但大多數針腳較長,約在0.8-1.0cm左右,應該是介於劈針和平針之間的過渡期。因此,這件繡品的年代不會太晚。繡品中心是釋迦牟尼的形象,他站在斑駁的岩石之前,這些岩石代表的正是靈鷲山。釋迦牟尼身披紅色袈裟,坦露右肩,赤腳立於蓮座之上,蓮座兩側各有一白色獅子,他的身後有背光和頭光裝飾,右手筆直指向地面,左手在胸前提起袈裟,這是在這類場景中經常出現的姿勢。其頭部上方則是一藍色華蓋,華蓋兩側各有一飛天形象。釋迦牟尼兩側各有一佛弟子和菩薩,均是赤腳立於蓮座之上的形象,菩薩基本上完整地保留了下來,但佛弟子除了頭部之外,身體的其餘部分均已缺失。繡品的右下方跪著四個男供養人,其中一人爲和尚裝扮,另外三人則均頭戴黑色襆頭,身穿藍色圓領袍,身後是一個站立的男性侍者;左下方是則跪有四個女供養人,頭梳髮髻,身穿窄繡襦,外罩半臂,身系各色長裙,有的披有披帛,一婦女身旁還跪有一男童,他的尺寸特別小,她們身後站立著一個身穿袍服的侍女。供養人身旁的題記上繡有“義明供養”、“一心供養”等字,但多已湮滅不可辨認。刺繡佛像在唐代十分常見,而且在敦煌文書中也經常可以看到。P.3432《龍興寺卿趙石老腳下依蕃籍所附佛像供養具並經目録等數點檢曆》中載有:“繡像壹片,方圓伍尺”;“繡阿彌陀像壹,長三箭,闊兩箭,帶色絹”。唐時一尺約爲30cm,吐蕃時期的一箭約等於50cm,即前一件繡像約方圓150cm,後一件繡阿彌陀佛像長150cm、寬100cm,比此件小。技術分析:組織結構: a. 本色絹經線:絲,無撚,單根排列,本色,30根/cm;緯線:絲,無撚,單根排列,本色,21根/cm;組織:1/1平紋。b. 本色麻布經線:絲,S撚,單根排列,本色,11根/cm;緯線:絲,S撚,單根排列,本色,8根/cm;組織:1/1平紋。刺繡: 繡線:絲,一般爲兩根Z撚以S撚併合;色彩:白、紅、黑、深藍、淺藍、褐、黃、土黃、綠、淺綠、棕等。針法:劈針等。 EnglishFrom Whitfield 1985:This is one of the most magnificent of all the compositions found in the hidden library at Dunhuang. As an embroidery it may rank with the Shaka Nyōrai Preaching, of similar size (207×157cm) and also of the eighth century, from the Kanshū-in, now in the Nara National Museum (see Nihon bukkyō bijutsu no genryū, p.254). Other items of embroidery in the Stein Collection at the British Museum are of a decorative character, but this work must have been equal in importance to the finest and largest of the paradise paintings on silk. The composition consists of a five-figured Buddha group, over which appears a canopy with apsarasas, and below are a number of donors. The Buddha stands on a lotus pedestal, beneath the blue canopy. His body is enclosed, to its full height, within an almond-shaped aureole that reaches to just above the nimbus around his head. Behind the mandorla is a rocky surround, representing Mt.Grdhrakūta, or the Vulture Peak, at Rājagrha, the scene of the preaching of the Lotus Sutra. The Buddha stands with his right shoulder uncovered and his right hand extended straight down, while his left grasps the hem of his robe, in the usual posture for Sākyamuni on this occasion (see also Vol.1, Pl.22). By good fortune and through the care with which the whole embroidery was folded, the central figure of Sākyamuni has escaped damage altogether, while the two Bodhisattvas have suffered only slight losses. It is the two disciples, already partly hidden behind the Bodhisattvas, who have been damaged the worst: as Stein noted in Serindia (Vol.Ⅱ, p.983), these figures fell along the line of folding when the hanging was put away, “and have for the most part been eaten away. ”Enough of the two figures survives, however, to reveal their individual characters and to show that their robes originally just touched the outermost contours of the rocky cliff. The two Bodhisattvas are almost completely visible. They and the disciples stand on lotus pedestals and seen in three-quarter view. As they are placed just in front of and a little below the disciples, the effect of the whole composition is to form a space enclosing the central Buddha, echoing the arrangement that would have been found if the group had been a sculptural one. This feeling for space and volume, despite the medium of embroidery in which it must have been especially difficult to achieve, is in itself powerful evidence of a date of execution early in the Tang dynasty when such concerns are characteristic of both sculpture and painting. That there were sculptural models for Sākyamuni on the Vulture Peak, though distant in time and space, is suggested by the presence of this representation in the New Delhi section of the painting of Famous Buddhist Images (see Vol.2, text figure, p.306), where Sākyamuni appears alone, against a rocky background. In that painting, several features indicate that the figure of Sākyamuni reflects, although not at first hand, a sculpture in stone. Like many of the other figures in the Famous Buddhist Images painting, this one is not coloured, but simply represented in ink outline. The mandorla enclosing the figure is straight at the sides and semicircular at the top, where it completely encloses the nimbus; its form and the small seated Buddha visible above Sākyamuni’s right shoulder strongly suggest that the original model was a free-standing stone stele. Only beyond its confines are there long coloured flames, and outside these the rocky forms of the Vulture Peak shaded in ink and some of them coloured. This seems appropriate in a painting which was primarily a record of famous images. Among the wall paintings at Dunhuang, the Sākyamuni Preaching on the Vulture Peak, in Cave 332, datable to the early Tang (Chūgoku Sekkutsu, Tonkō Makkōkutsu, Vol.3, Pl.88) is close to the embroidery in scale and composition. The scene is painted on the north face of the pillar behind the main images, in the corridor at the back of the cave. Sākyamuni, clad in a red robe, stands between two Bodhisattvas, Avalokitesvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta. His nimbus and mandorla have a broad edging of flames, and the outlines of cliffs and mountain peaks appear behind. There are no disciples, and three canopies rather than one complete the composition. The colours in the wall painting have suffered a good deal of abrasion and loss, so that a detailed comparison is not possible. As a general impression, however, the figure of Sākyamuni appears somewhat stiffer, the robe pulled up tightly under the right arm, crossing the chest almost horizontally rather than falling gracefully in a single curve from the left shoulder. In both figures the edges of the outer garment are seen to wave (revealing a lining of a different colour) across the chest, around the shoulder and upper left arm and as two wavy edges falling from the gathering in the Buddha’s left hand. The more schematic character of the wall painting can be judged in this last fall, since the waves are juxtaposed and mirror each other exactly, while in the embroidery each pursues its own rhythm, and the differences in the undulations help to reveal the shape of the figure. The schematic character of the wall painting is on the whole closer to the depiction of Sākyamuni in the Famous Buddhist Images painting than to the embroidery: note especially the way in which the upper edge of the robe is brought up close under the right arm, and the stiff waves of the edges of the robe. The same double lines are used, however, in both the silk painting and the embroidery to indicate drapery folds, so all three depictions have points in common. In the embroidery, frequent slight variations in colour enhance the liveliness already present in the initial outlines-each fold is narrowly outlined in blue, always following the underdrawing in ink, which is visible in every place where the threads are broken or missing. Turning to the depiction of the facial features in the several figures of this embroidery, we can observe subtle variations here also. The elderly disciple on Buddha’s left has the most vigorous appearance, with blue outlines strongly accenting all the main lines and even outlining his teeth, and used in a regular vertical crosshatching of the eyebrow, indicated on the silk ground beneath by an area of ink wash. The iris of his eye is painted in black ink directly on the silk ground without any overlying embroidery. Of the face of his companion opposite, enough remains to show that he had smooth features: the iris is again rendered in black ink on the silk ground, but the eyebrow above is embroidered with long thin stitches of blue interspersed with others of the pale silvery silk used for the rest of the head, so that the eyebrow appears smooth and delicate. In the Bodhisattvas, the eyebrows are indicated by single blue arcs as are the inner upper edge of the orbit and the almond-shaped contour of the eye. The iris is painted in ink, not on the silk ground beneath, but on the embroidery. The nose is outlined with a single line of stitches once perhaps tinged with red but now faded to a very pale yellow, as have the lips. Even greater care was taken with the countenance of the Buddha. His hair is of the deepest indigo, edged in the lighter blue that also outlines the face and models the ears. In the centre of the hair at the base of the usnisa, this same lighter blue frames a small circle of the exposed white silk ground representing a jewel. The slender, finely arched eyebrows are in a lighter shade than the indigo used for the hair. The eyes, outlined in blue, are filled with horizontal rows of chain stitch in a whiter silk than the rest of the face: against this the irises, painted in black ink directly on the silk ground, stand out clearly and indeed seem have been lightly padded from behind so as to appear slightly raised. The edges of the eye orbit, the whole of the nose, the mouth, complemented by associated modelling lines and chin line. Are all in a golden colour. For the rest of the face, the rows of stitches follow both the outer contours and the inner features, thus revealing the whole circle of the orbit merely through the arrangement of the stitches. The dramatic effect of the modelling must originally have been much strengthened by differences of colour: today many of these colours have greatly faded, while the blues of the indigo have remained strong since they were initially created by oxidation. Although these subtleties only reveal themselves on close examination, they do account for the extraordinary presence of the figures, and testify to the early date of the whole composition. Only in the early and high Tang do we find such close and constant attention to details that constantly serve to enhance the movement and form of the figures. Details such as the hands of the two Bodhisattvas show great sensitivity: those of the Bodhisattva on Buddha’s right are in anjalimudrā, palms pressed together, but with the index of right hand just crooked behind the rest. On Buddha’s left, the Bodhisattva’s right hand is extended, palm outwards; the thumb is missing but the wrist is intact and completely relaxed. Wrist and fingers are again seen to perfection in the left hand: no opportunity to depict graceful movement has been lost. In all these details the embroidery has followed the original cartoon in ink, which set out even such minor details as the flowers and buds scattered by the heavenly beings above. It invites comparison with the most delicate of the early Tang wall paintings, such as the Bodhisattva as Guide of Souls in Cave 205(Vol.2, text figure, p.302), or a donor in Cave 401(Chūgoku Sekkutsu, Tonkō Makkōkutsu, Vol.3, Pl.7). Such comparisons inviting an early date are confirmed when we examine the demure attitudes of the donors below: the ladies in high-waisted dresses, with shoulder shawls: the men with modest cap-ribbons falling naturally; while at the top the canopy is of the domed kind, with curved ribs and segments alternating in colour, that we have already seen in the Representations of Famous Buddhist Images(Vol.2, Fig.9). As noted above, the panel, apart from the losses sustained through long storage in a folded state, is in an amazingly good state of repair. The edges on both sides have been well preserved, and very little, if any, of the top and bottom edges has been lost, other than perhaps a few centimetres of unembroidered space. The panel is made up of hemp cloth, now visible in many place, although this was originally entirely covered by thin silk of a balanced close weave. Although this silk has now largely perished, it can still be seen easily, particularly in the upper left corner. Both the thin silk ground and the hemp cloth support are in fact formed of three widths of material sewn together, the seams being completely hidden when beneath the embroidery, but now easily visible on the plain ground due to the better preservation of the silk along the edges of the seams. After the embroidery reached London, it was couched on a new linen backing and mounted on a stretcher as a panel. For many years it hung in a glazed frame on the landing of the North Staircase of the British Museum, protected by a curtain. When the upstairs galleries were renovated in 1971, a special case was prepared for it so that it is frequently on view at entrance to Oriental Gallery Ⅱ. Close examination of the embroidery shows that the design was first drawn in outline in ink directly onto the silk ground. Following this preliminary drawing, the main contours were first worked, most of them in dark blue silk, in lines of split stitch. In some places, for example in the contours of the rock of the mountain and in some of the drapery of the Bodhisattva on the left, these outlines were done in brown instead of blue. After this each of the areas enclosed by the outlines was filled by closely packed soft unplied floss silk. Stein describes this as “worked solid in satin stitch, ”but it many perhaps be split stitch, with long over-lapping stitches to produce a satiny finish. In general these lines fill the area in the same way that a field many be ploughed, following the outer boundaries and gradually reducing the area left to be done. There are , however, a number of variations: in many places the outlines are dispensed with and, just as in kesi (kossu; 緙絹) weave, a consistent division produces a line within a single colour, as in the centre line of the breast of the Bodhisattva on the right. This technique is also used in conjunction with a change of colour, for instance on the breast of the Buddha himself; it is used again to mark the edges of the petals in the lotus pedestals, and of the floral motifs in the embroidered hems of the garments of the two Bodhisattvas. The rock structure of the Vulture Peak, in several colours, is distinguished both by outlines in blue or brown, and occasionally by setting the filling stitches at right angles in adjacent facets of the rock, giving a sharp variation in reflectance. Within each area so filled, there are subtle variations in colour, as well as differences in the length of stitch and type of silk used. For most of the large areas, the silk used is a single, rather full, unplied floss silk, and the stitches are long, often between 8 and 10 mm in length, giving a satiny appearance. In many places, however, as it was worked behind the needle, the two strands of the silk lightly twisted together (within each strand the silk is of course untwisted): this can be seen for example in the blue rock. In places where the silk is finer, this twisting of the strands is correspondingly tighter, as can be seen in some areas of the Bodhisattvas’ robes. Sometimes the stitches were much shorter in order to give a different surface texture. The clearest example of this is in the stitch (still a split stitch but with short stitches instead of long ones) used for the Buddha’s extended right arm. Here a totally different effect is achieved since each line of split stitch, instead of being closely packed, is quite separate from its neighbours, leaving the underlying thin silk ground clearly visible. When the embroidery was new, this technique must have resulted in an enhanced luminosity of the forearm and hand, distinct from the golden colour of the upper arm and shoulder; indeed this is still true today. In the hand itself, the way in which the lines of stitches follow the curves of the fleshy parts of the palm and fingers can be seen directly in the plate (Pl.1-2). The outlines of this hand and of the arm right up to the shoulder are in a silk which today appears completely black, without a hint of blue. ChineseFrom Whitfield 1985:這幅刺繡作品色彩豐富,技藝精湛,是敦煌藏經洞出土的最優秀的作品之一。從刺繡的做工上說,可與奈良國立博物館藏(勸修寺舊藏)的《釋迦牟尼說法圖繡帳》 (見《日本佛教美術源流》,254頁)相媲美(該作品製作於8世紀,尺寸爲207×157cm)。大英博物館所藏的斯坦因收集品中,還有其他一些刺繡作品,但多是裝飾性的,而該作品則同其他絹繪淨土圖一樣氣勢壯觀。此圖由五尊佛像構成,上部是華蓋和飛天,下部是衆多的供養人像。佛陀站立在青色華蓋遮敝的蓮華寶座上,扁桃形的身光環繞著身體與頭光等高。曼陀羅的背後有一座岩山,可以想見,這是《法華經》中所說的靈鷲山。佛陀偏袒右肩,右手垂直下放,左手執衣襟。這是所有靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖中所共有的一種姿勢(參見卷1,圖22)。該刺繡曾長期疊放在藏經洞中,所以兩尊菩薩的像有部分破損,幸運的是主尊釋迦牟尼保存完好,菩薩略有殘損,而破損最嚴重的是兩尊菩薩背後只露出半個身子的兩尊弟子的像。造成這種破損的原因,正如斯坦因在《西域》(Serindia,卷2,983頁)中分析的那樣,是在人們取下畫上的吊繩折疊存放時,這些部位正好處在折線上。在斯坦因發現它時,這些像就已幾乎散失,但通過殘存部分仍能辨別出這二尊弟子的容貌,也能確認他們的衣物本是連在突兀的斷崖上的。二尊菩薩基本保存完好,和二尊弟子一樣,斜向前方站立在蓮華座上。他們緊挨弟子站在前方,在圖中的位置比弟子略低。主尊周圍各尊佛像的這種佈局,與我們在雕像中所見到的各尊佛像的陳列方式一樣,顯現出一定的空間進深。從技術上說,用刺繡是很難表現出空間感和量感的,但是這副作品卻實現了這一點。這一特點有力地証明了該作品的製作爲初唐時期。因為在初唐時期,無論是繪畫還是雕刻,人們都越來越注重表現空間感和量感。新德里國立博物館藏的《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》(參見卷2,解說插圖,306頁)中也有用岩山做背景的釋迦牟尼獨尊像。雖然兩幅作品産生的年代和地點相差很遠,但可以推測,過去確實存在有一座雕像,《靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖》中的釋迦牟尼就是依據這座雕像創作的。《瑞像圖》中的釋迦牟尼像雖然沒有直接摹寫石雕像,但在很多地方我們都能夠找到石雕像的影子。以岩山做背景的佛像,與其他諸像一樣,只使用墨線而無色彩。環繞佛像的背光,兩側爲豎立的直線,上端呈半圓形,項光被完全納入其中。這種背光的表現形式、釋迦牟尼右肩上方的小坐像,使人強烈地感到這幅作品是以石雕爲原型創作的。只有彩色的長長的火焰光越出了背光的界線,外側是墨線勾勒的彩色的靈鷲山岩石,這種表現手法正適合於該作品記錄瑞像的目的。在敦煌壁畫中,初唐時期建造的第332窟(《中國石窟•敦煌莫高窟》卷3,圖88)的壁畫裏,也有與此非常相似的《靈鷲山釋迦牟尼說法圖》。該圖繪在洞內後方回廊部位的方柱北面,釋迦牟尼身裹紅色袈裟,兩側站立著觀音、勢至二尊菩薩。背光和項光附有寬大的火焰紋,背後用線描繪出了斷崖或山上裸露的岩石。畫中沒有弟子,只有三頂華蓋,而非完整構圖。壁畫的色彩漫漶、脫落嚴重,無法對細節部分進行比較和研究。然而,此壁畫給人的整體印象是,釋迦牟尼的像比較生硬,通常從左肩用柔和的弧線來描繪的衣服,在此用斜線幾乎橫切前胸,看似牢牢夾在右腋下方。外衣的邊緣呈波浪狀(能看到襯裏的不同顔色);外衣從胸前穿過,從肩繞至左上臂,集中到左手,再從左手處形成兩條紐帶垂落下來。這些細節與本圖中的佛像相同。比較雙方對最後紐帶部分的處理,可以看出壁畫相對顯得有些形式化。壁畫中,紐帶的波紋兩條兩條地整齊地並列在一起,而刺繡中二條紐帶則分別有著自己的運動節奏,呈現出不同的波浪起伏,這種處理方法有助於刻畫釋迦牟尼的形象。從整體上看,與本圖的刺繡作品相比,此幅壁畫的形式化的表現方法,更接近於《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》。特別是橫過前胸的衲衣上端被右腋牢牢夾住、衲衣邊緣的波浪起伏用直線生硬地勾畫,這些都很引人注目。而另一方面,絹繪的瑞像圖和本刺繡作品中,衣褶都用雙線表示,所以說三者之間存在共同點。刺繡作品中,僅有的幾種顔色變化頻繁,進一步增加了樣本已具有的生動感。袈裟則用藍色線沿著底稿的墨線細緻地刻畫,在那些絲線已斷裂、缺失的地方,我們還可以看到底稿的墨線。再看諸佛的面容,其表現也有一些細微的變化。表情最爲生動的,是站在如來左邊的年老弟子,包括牙齒的輪廓線在內,主要線條均用藍色突出出來。眉毛是在絹底上用淡墨畫的,粗粗的,上用線繡出一些細毛。黑眼珠是在絹底上直接用墨描繪的,沒用刺繡。右側弟子面部雖然只殘留一小部分,但能看出他表情柔和。黑眼珠也是在絹底上用墨點出的,眉毛則使用藍色線,針腳細而長。臉部到頭部使用淡銀色線,幾種顔色搭配在一起,顯得柔和、細膩。二菩薩的眉毛與眼窩線及杏核眼的輪廓,都使用了一根藍色的弧線來表示。而黑眼珠沒畫在絹底上,是用墨繪在了刺繡上。鼻梁線與嘴唇線使用了相同的顔色,當初可能是淡紅色,但現在已褪變爲黃色。佛陀的面容更是下了許多功夫。頭髮是深藏青色,臉部、耳朵的輪廓線都使用了明快的藍色。頭髮中央的肉髻珠的位置,留出了圓形的白色絹底,周圍圈以明快的藍色,看似寶石。細細的眉毛呈優美的弧形,顏色與頭髮的深藏青色相比有淡淡的陰影。眼睛輪廓爲藍色,眼白則用比臉部還白的絹絲,採用鎖繡的手法水平刺繡而成。而黑眼珠則是在絹底上直接用墨描繪。黑眼珠具有鮮明的立體感,其實是在下面墊了東西使其稍稍凸出來一點。眼窩、鼻、唇、下顎以及裸露的身體,均使用金黃色。面部其他部分則分別沿著臉的輪廓線和五官的輪廓線刺繡而成,看起來像是打著漩兒。裸露的身體當初肯定有著強烈的色彩變化,但現在,大部分已褪色,只有深藏青色還殘留著它的鮮豔。只有在對該作品進行仔細的研究之後,我們才能發現這些細節部分的精妙之處。這些細節不僅表現出其在佛像刻畫中的非凡之處,也證明了該作品本身的製作年代之早。因爲這種極其注重細節並以此提高佛像生動感的特色,只在初唐到盛唐間的作品中才能見得到。再看二尊菩薩的手,我們會發現對細節部分的刻畫幾乎到了細緻入微的地步。如,合掌侍立在釋迦牟尼右側的菩薩,右手食指彎曲,藏在其他手指的陰影裏。侍立在左側的菩薩,右手伸開,掌心向外,拇指雖已殘缺,但手腕處保存完好,並表現出了柔弱無力的樣子。其左手的手腕和手指完整地保留至今,仍然優雅生動。這種細節是沿著底稿上的墨線用刺繡來刻畫的。圖上方飛天周圍散落的花朵、花蕾等細節的刻畫方法也與此相同。綜上所述,和敦煌初唐時期的壁畫相比,該作品可以和第205窟西壁的《引路菩薩圖》(卷2,解說插圖,306頁)、第401窟的《供養菩薩圖》(《中國石窟•敦煌莫高窟》卷3,圖7)等最爲精緻的壁畫相媲美。可與這些早期作品相媲美的地方,還有對圖下部供養人像文雅姿態的刻畫:女供養人在齊胸的裙子外披肩巾、男供養人柔軟垂落的襆頭等。另外,圓頂華蓋是通過表現不同的材料的交互將顔色分開,在《釋迦牟尼瑞像圖》(卷2,Fig.9)中也能見到這種表現方式。前面已經介紹過,由於此作品被長時間折疊存放,除殘損部分外,其餘部分保存完好得令人驚訝。畫面的兩端都完好無損,上下邊即使是保存下來,也不過是數釐米沒有刺繡圖案的絹底。此作品本來是在麻布上鋪了一層質地緻密的薄絹。薄絹已損壞相當嚴重,但畫面右上部的部分卻殘留了下來。整個作品是用三幅這種薄絹面和麻布裏重疊的布料縫合而成的,縫合的針眼本應是完全隱蔽在刺繡下面的,但現在,部分針眼在絹面上已經隨處可見。此繡品運送到倫敦以後,被重新用麻布裱褙,變得象幅油畫一樣,還加上了玻璃鏡框。在很長一段時間裏,覆蓋著幕布挂在大英博物館北部樓梯的平臺上。到了1971年,博物館二層陳列室改建時,才被放進特製的匣子裏,擺放在東方繪畫陳列室入口處顯眼的地方。仔細查看該作品,我們會發現其是先將底樣直接描繪在絹底上,然後照樣刺繡的。主線基本上是用深藏青色絲線割繡。但有一部分如裸露的山石、侍立右側的菩薩的袈裟等等,則用褐色取代了藏青色。然後用柔軟的單股絹絲認真填平用線圈起來的範圍,雖然斯坦因稱其爲緞繡,但從其長而平滑的針腳看,恐怕應是割繡。一般來說,用刺繡填埋輪廓線內的空白,就像耕地一樣,沿輪廓線來回做往復運動,逐漸縮小空白部分。但在這裏,不只是用這種方法,而是産生了各種變化。不僅運用直線針,更多則採用織錦似的針法,如侍立左側的菩薩胸部的中線,就是在同種色線繡出的部位中加上非常明顯的分界線。此種手法,除了使釋迦牟尼胸部顔色更具變化外,也使蓮華座的花瓣兒更醒目、二尊菩薩的衣邊兒花紋爲更突出。背景中岩石臨接的地方使用相互垂直的針腳,表現出了岩石表面的凹凸不平。在填埋各部分時,通過變換針腳的長短或所用絲線的種類來産生色彩的微妙變化。面積較大的部分則幾乎都是使用未撚的單股線,針腳有8-10mm,表面顯得很有光澤。但很多地方繡針在往返時使兩股線輕輕地撚在了一起(單股線不用撚)。這一特點在岩山的青色部分表現得非常明顯,而且在菩薩的衣裳上也是隨處可見,用細線繡的部分,線都撚在一起,非常細密。同時這些地方針腳較短,表面的感覺也略有不同。其中一個明顯的例子,就是釋迦牟尼伸向下方的右手,上下部分的繡法雖然相同,但針腳從上部到下部逐漸由長變短。並且,下部所繡的各線沒有緊密填補空間,針與針之間有距離,從隙間露出了薄絹底,産生出與上部完全不同的效果。與我們今天所看到的情形不同,這幅作品在剛完成時,前臂和手掌因這種技法而産生了與金色的肩部和上臂部不同的效果,其亮度要更大一些。這種效果現在還沒有完全消失,從手部擴大圖(圖1-2)上可以看到,刺繡的線沿著手掌及手指的曲線描繪出不同的弧度。現在,其手的前部及手腕到肩等處的輪廓線變成了黑色,已看不出原來的藍色了。 Zwalf 1985This splendid embroidery, as large as any Dunhuang paintings found by Stein, shows the Buddha in the rocky surround of the Vulture Peak (Ghṛdhrakūṭa) at Rājagṛha preaching the ‘Lotus Sūtra’. It had been carefully folded to protect the Buddha, but beneath the fold the two disciples representing the Hīnayāna are damaged. Celestial figures scatter flowers from above, and the donor family is ranged on either side below. The style and quality make this one of the finest Tang dynasty works. Rawson 1994:Rawson 1994:All types of textile art flourished during the Tang dynasty (AD 618-906) in China. An important group of Tang textiles has recently been found in excavations at the Famensi at Fufeng, in Shaanxi province; gifts to this monastery evidently included clothing as well as glass, silver and ceramics. Embroidery also continued to be developed and was used for large images of the Buddha built up in satin and chain stitch. Most of the textiles found by Aurel Stein at Dunhuang in Gansu province, including banners, altar hangings and monks’ apparel, follow the Buddhist convention of being made up of small cut pieces of different cloth. These ‘patchwork’ items provide an invaluable cross-section of the different types of silk cloth and embroidery available at the time (BM MAS.857).Trade along the Silk Route was at its most vigorous during the Tang dynasty, and travellers record the bazaars of the Middle East as being full of Chinese patterned cloth and embroideries. Simultaneously we are told that the Tang capital at Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) was populated by large numbers of Iranian craftsmen. A silk weave now known as “weft-faced compound twill” appears among Chinese textiles for a few centuries from about AD 700. This may well have been a technique introduced by foreign weavers, as it seems to have been developed originally in Iran. In the West it was particularly associated with repeating designs of roundels enclosing paired or single animals, with flower heads or rosettes between the roundels (BM MAS.876 and 877). The scroll design with flowers and birds occurs in ceramics and other decorative arts from the Tang dynasty onwards. The Getty’s curatorial team suggests the title as Miraculous Image of Liangzhou (Fanhe Buddha)

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END