Period:Unknown

Materials:iron

Technique:cast

Dimensions:Length: 5.10 centimetres

Description:

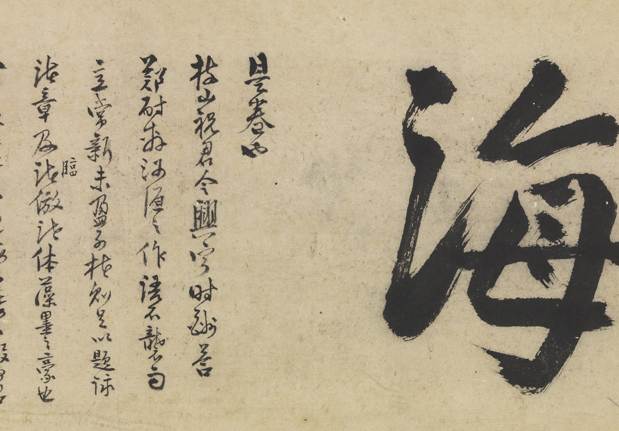

Fragment of an (opium?) pipe made of iron.

IMG

![图片[1]-smoking-pipe; opium-pipe(?) BM-MAS.959-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01155601_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-smoking-pipe; opium-pipe(?) BM-MAS.959-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01155603_001.jpg)

Comments:Opium and the British EmpireThe Chinese-made, opium-related paraphernalia in the British Museum relates to the history of Anglo-Chinese trade from the late Eighteenth to the mid Twentieth Century. This history is extremely complicated but is the subject of many insightful texts, including Frank Sanello and William Travis Hanes 2007 The Opium Wars. Put very simply the opium trade arose from a serious trade imbalance resulting from the importation of tea and other luxury goods from China into Britain. China only accepted silver in payment for tea, and since it proved difficult to find commodities that the nearly self-sufficient Chinese wanted, Britain became alarmed at the outward flow of silver. The British eventually resorted to cultivating opium in India and shipping it to China for sale. This resulted in the new, dangerous problem of widespread, recreational use of opium throughout China. In 1729 the Chinese prohibited smoking opium and in 1800 an imperial edict banned its cultivation and importation. Nonetheless opium was still smuggled into China. The Daoguang Emperor appointed Lin Zexu to halt the illicit trade in Guangdong. In 1839 he ordered 20,000 chests of foreign opium to be destroyed. In a climate of escalating incidents and claiming they deserved compensation for the opium, the British initiated the First Opium War (1839—42). China lost and was forced to temporarily open five ports to foreign merchants and to permit the territorial concession of Hong Kong. Drug trading was resumed, relations again worsened and a second war between China and the Western alies ensued (1856 to 1860) and more unequal treaties were signed including one which forced the legalisation of opium in China. This second war culminated in the allied destruction of the Summer Palace (Yuanming yuan) in 1860. It was not until 1960 that Mao Zedong, following a ten year anti-drug campaign, was able to proclaim that opium addiction had ended in China.

Materials:iron

Technique:cast

Dimensions:Length: 5.10 centimetres

Description:

Fragment of an (opium?) pipe made of iron.

IMG

![图片[1]-smoking-pipe; opium-pipe(?) BM-MAS.959-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01155601_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-smoking-pipe; opium-pipe(?) BM-MAS.959-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01155603_001.jpg)

Comments:Opium and the British EmpireThe Chinese-made, opium-related paraphernalia in the British Museum relates to the history of Anglo-Chinese trade from the late Eighteenth to the mid Twentieth Century. This history is extremely complicated but is the subject of many insightful texts, including Frank Sanello and William Travis Hanes 2007 The Opium Wars. Put very simply the opium trade arose from a serious trade imbalance resulting from the importation of tea and other luxury goods from China into Britain. China only accepted silver in payment for tea, and since it proved difficult to find commodities that the nearly self-sufficient Chinese wanted, Britain became alarmed at the outward flow of silver. The British eventually resorted to cultivating opium in India and shipping it to China for sale. This resulted in the new, dangerous problem of widespread, recreational use of opium throughout China. In 1729 the Chinese prohibited smoking opium and in 1800 an imperial edict banned its cultivation and importation. Nonetheless opium was still smuggled into China. The Daoguang Emperor appointed Lin Zexu to halt the illicit trade in Guangdong. In 1839 he ordered 20,000 chests of foreign opium to be destroyed. In a climate of escalating incidents and claiming they deserved compensation for the opium, the British initiated the First Opium War (1839—42). China lost and was forced to temporarily open five ports to foreign merchants and to permit the territorial concession of Hong Kong. Drug trading was resumed, relations again worsened and a second war between China and the Western alies ensued (1856 to 1860) and more unequal treaties were signed including one which forced the legalisation of opium in China. This second war culminated in the allied destruction of the Summer Palace (Yuanming yuan) in 1860. It was not until 1960 that Mao Zedong, following a ten year anti-drug campaign, was able to proclaim that opium addiction had ended in China.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END