Period:Unknown Production date:2007

Materials:paper

Technique:printed

Subjects:landscape

Dimensions:Height: 45 centimetres (original paper size) Imperial mount) Width: 45 centimetres

Description:

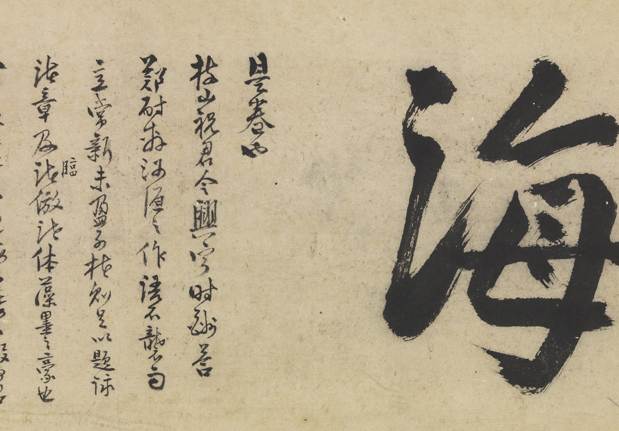

Digital picture, inkjet print on Epson textured fine art paper. ‘Phantom Landscape III’, leaf one, by Yang Yongliang, Shanghai, 2007.

IMG

![图片[1]-print BM-2008-3012.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_00476158_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-print BM-2008-3012.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_RFC37967.jpg)

Comments:The image is formatted as a circular fan and printed in tones of black and grey ink. It depicts a landscape in a style reminiscent of the “one-corner” compositions popular during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). The image is composed of a strip of land in the lower left foreground, water and misty shoals in the midground, and a substantial mountain in the distance in the upper right. Behind this mountain, more peaks that are partially obscured by heavy mist appear and trail off towards the upper left. In a Southern Song painting, the near ground would feature trees and possibly a scholar enjoying nature. In the distance a mountain dotted with trees and textured with ink strokes representing vegetation would appear. Here the artist substitutes lattice-work metal towers, or pylons, that carry overhead electricity lines for the craggy pine trees expected in a Song dynasty landscape. The foreground also features ramshackle buildings, a bicycle, and some rubbish. The distant mountain at first seems to be covered with trees and textured by ink strokes; however, a second look reveals that the trees are tall metal pylons and the texture is provided by densely layered images of monumental skyscrappers. The impression of a landscape dissolves into an image entirely composed of manmade forms and urban representation. Instead of signing his work with a traditional red name seal, Yang has impressed a square relief stamp on the work that is pattterned after the metal manhole covers visible in Chinese streets. The artist was born in China in Jiading (Shanghai area) and as a young student studied traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy before attending the Shanghai Fine Art Institute, where he specialized in decoration and design beginning in 1996. In 1999 he attended the China Fine Art Institute, Visual Communication Department, Shanghai branch. In 2005 he started his career as as an artist with the stated goal of “creating new forms of contemporary art.” 2008,3012.1 and 2008,3012.2 belong to a series of four images Yang created in 2007 in the format of circular, fan-shaped album leaves. The works all depict landscapes whose imagery borrows from and subverts the visual language and meaning of Southern Song dynasty paintings. Using photography and digital manipulation Yang Yongliang created a new visual effect in order to comment on the breathtaking and sometimes frightening pace of urbanization in modern China. His works at first glance appear to celebrate the beauty of nature by closely following the well-known format of Southern Song nature paintings, but his images are composed entirely of manmade materials, such as cement buildings, metal pylons, and telephone wires and electricity cables. China’s massive population shifts into urban centres threaten the natural environment and put stress on traditional agrarian ways of community-based life. People’s direct ties to a natural landscape are rapidly disappearing. Agrarian lifestyle is being replaced by the throbbing pace of urban life and all it entails. A new emphasis on the individual and personal economic gain has fostered a new lifestyle that brings with it pseudo-anonymity as people crowd together and live in monumental skyscrapers where you seldom know your neighbours or have family. The buildings too are often cut off from natural surroundings. Yang Yongliang’s digital manipulations are clever in their inversion of the imagery of Song dynasty painters and he has created works that are themselves visually attractive. His cold, hard urban images possess a layer of romantic beauty with their mists and towering forms. By making his works “beautiful” he has managed to make them much more than a mockery of modern life. Instead they subtley pose the difficult question of whether urban life can be simultaneously loathsome and posses an intrinsic beauty. Yang carefully made these riffs on Southern Song landscapes because the earlier works have long been regarded in China as a sublime expression of nature’s beauty and mystery. Are Yang’s images meant to be taken as expressions of a city’s beauty or of the terror of urban encroachment. Every detail of Yang’s compositions intentionally recalls Song dynasty painters who employed brush and ink techniques to create soft washes for mists and distant mountains and called upon a variety of ink brushstrokes to outline craggy trees and texture land surfaces by imbuing them with the feel of rock, soil, and low vegetation. The traditional texture strokes, or cun, have been recast into a modern idiom in Yang’s work. He pioneered a method of using digitally manipulated photographic images of buildings, including skyscrapers, and of telephone poles and pylons for suspending electric wires as cun. He arranges and layers these stark modern images, sometimes veiling them by mist, so that they appear remarkably close to the Southern Song prototypes. Yet, some modern elements read with naked clarity thereby ensuring that the viewer simultaneously sees the modern and the ancient, toggling back and forth between the two readings of the image as “12th century landscape” and modern China. His images seem simultaneously beautiful and repulsive, restful and threatening, timeless and changing. Yang’s work forces us to ponder China’s modernization. The artist comments on his own work in a few statements that support the s above. Yang writes, “City and Landscape, I love them and hate them at the same time. I love the familiarity of the city, more so to hate it growing too fast and invading everything around it an unexpected speed. ” And “I love the depth and inclusiveness of the traditional Chinese art, more so to hate its non-progress[ive] attitude. I have input this complex feeling to my blood and lift it out to form my artwork. Ancient Chinese expressed their appreciation of nature and feeling for it by painting the Landscape. In contrast, I make my Landscape to criticise the realities in [before] my eyes.” [Quote from sales catalogue, ‘Phantom Landscape’, OFoto Gallery, late 2007-early 2008] Yang’s use of digital photography in a painterly way is itself an act that resonates with and updates traditional Chinese artistic expression. A lot of creative energy in China over the last few centuries hase centred on manipulating painted imagery into formats suitable for other medium—taking paintings as a lead for the imagery on ceramics or on jade boulder carvings. Yang enters into this conceptual framework by taking the medium of photography and digitally manipulates it so that the end result is a contemporary art form that seems simultaneously to be both a painting and a photography print. Phantom Landscapes IIIShenshi shanshui san 蜃市山水叁In his landscapes, Yang Yongliang achieves strikingly visual effects by digitally manipulating photographic images. At first sight, the two prints appear like idyllic landscapes painted in ink, reminiscent of classic landscapes from the Song dynasty (960–1279). On closer inspection, Yang has substituted trees with telegraph poles and mountains with clusters of skyscrapers, pointing to the rapid transformation of cities and landscapes in present-day China.Yang Yongliang was born in 1980 in Jiading near Shanghai where he currently lives. He studied traditional calligraphy and painting before graduating in design from the Shanghai Fine Arts Institute.Yang Yongliang 楊泳梁 (born 1980)Shanghai 2007Digital picture, inkjet print on Epson textured fine art paperAsia 2008,3012.1

Materials:paper

Technique:printed

Subjects:landscape

Dimensions:Height: 45 centimetres (original paper size) Imperial mount) Width: 45 centimetres

Description:

Digital picture, inkjet print on Epson textured fine art paper. ‘Phantom Landscape III’, leaf one, by Yang Yongliang, Shanghai, 2007.

IMG

![图片[1]-print BM-2008-3012.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_00476158_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-print BM-2008-3012.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_RFC37967.jpg)

Comments:The image is formatted as a circular fan and printed in tones of black and grey ink. It depicts a landscape in a style reminiscent of the “one-corner” compositions popular during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). The image is composed of a strip of land in the lower left foreground, water and misty shoals in the midground, and a substantial mountain in the distance in the upper right. Behind this mountain, more peaks that are partially obscured by heavy mist appear and trail off towards the upper left. In a Southern Song painting, the near ground would feature trees and possibly a scholar enjoying nature. In the distance a mountain dotted with trees and textured with ink strokes representing vegetation would appear. Here the artist substitutes lattice-work metal towers, or pylons, that carry overhead electricity lines for the craggy pine trees expected in a Song dynasty landscape. The foreground also features ramshackle buildings, a bicycle, and some rubbish. The distant mountain at first seems to be covered with trees and textured by ink strokes; however, a second look reveals that the trees are tall metal pylons and the texture is provided by densely layered images of monumental skyscrappers. The impression of a landscape dissolves into an image entirely composed of manmade forms and urban representation. Instead of signing his work with a traditional red name seal, Yang has impressed a square relief stamp on the work that is pattterned after the metal manhole covers visible in Chinese streets. The artist was born in China in Jiading (Shanghai area) and as a young student studied traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy before attending the Shanghai Fine Art Institute, where he specialized in decoration and design beginning in 1996. In 1999 he attended the China Fine Art Institute, Visual Communication Department, Shanghai branch. In 2005 he started his career as as an artist with the stated goal of “creating new forms of contemporary art.” 2008,3012.1 and 2008,3012.2 belong to a series of four images Yang created in 2007 in the format of circular, fan-shaped album leaves. The works all depict landscapes whose imagery borrows from and subverts the visual language and meaning of Southern Song dynasty paintings. Using photography and digital manipulation Yang Yongliang created a new visual effect in order to comment on the breathtaking and sometimes frightening pace of urbanization in modern China. His works at first glance appear to celebrate the beauty of nature by closely following the well-known format of Southern Song nature paintings, but his images are composed entirely of manmade materials, such as cement buildings, metal pylons, and telephone wires and electricity cables. China’s massive population shifts into urban centres threaten the natural environment and put stress on traditional agrarian ways of community-based life. People’s direct ties to a natural landscape are rapidly disappearing. Agrarian lifestyle is being replaced by the throbbing pace of urban life and all it entails. A new emphasis on the individual and personal economic gain has fostered a new lifestyle that brings with it pseudo-anonymity as people crowd together and live in monumental skyscrapers where you seldom know your neighbours or have family. The buildings too are often cut off from natural surroundings. Yang Yongliang’s digital manipulations are clever in their inversion of the imagery of Song dynasty painters and he has created works that are themselves visually attractive. His cold, hard urban images possess a layer of romantic beauty with their mists and towering forms. By making his works “beautiful” he has managed to make them much more than a mockery of modern life. Instead they subtley pose the difficult question of whether urban life can be simultaneously loathsome and posses an intrinsic beauty. Yang carefully made these riffs on Southern Song landscapes because the earlier works have long been regarded in China as a sublime expression of nature’s beauty and mystery. Are Yang’s images meant to be taken as expressions of a city’s beauty or of the terror of urban encroachment. Every detail of Yang’s compositions intentionally recalls Song dynasty painters who employed brush and ink techniques to create soft washes for mists and distant mountains and called upon a variety of ink brushstrokes to outline craggy trees and texture land surfaces by imbuing them with the feel of rock, soil, and low vegetation. The traditional texture strokes, or cun, have been recast into a modern idiom in Yang’s work. He pioneered a method of using digitally manipulated photographic images of buildings, including skyscrapers, and of telephone poles and pylons for suspending electric wires as cun. He arranges and layers these stark modern images, sometimes veiling them by mist, so that they appear remarkably close to the Southern Song prototypes. Yet, some modern elements read with naked clarity thereby ensuring that the viewer simultaneously sees the modern and the ancient, toggling back and forth between the two readings of the image as “12th century landscape” and modern China. His images seem simultaneously beautiful and repulsive, restful and threatening, timeless and changing. Yang’s work forces us to ponder China’s modernization. The artist comments on his own work in a few statements that support the s above. Yang writes, “City and Landscape, I love them and hate them at the same time. I love the familiarity of the city, more so to hate it growing too fast and invading everything around it an unexpected speed. ” And “I love the depth and inclusiveness of the traditional Chinese art, more so to hate its non-progress[ive] attitude. I have input this complex feeling to my blood and lift it out to form my artwork. Ancient Chinese expressed their appreciation of nature and feeling for it by painting the Landscape. In contrast, I make my Landscape to criticise the realities in [before] my eyes.” [Quote from sales catalogue, ‘Phantom Landscape’, OFoto Gallery, late 2007-early 2008] Yang’s use of digital photography in a painterly way is itself an act that resonates with and updates traditional Chinese artistic expression. A lot of creative energy in China over the last few centuries hase centred on manipulating painted imagery into formats suitable for other medium—taking paintings as a lead for the imagery on ceramics or on jade boulder carvings. Yang enters into this conceptual framework by taking the medium of photography and digitally manipulates it so that the end result is a contemporary art form that seems simultaneously to be both a painting and a photography print. Phantom Landscapes IIIShenshi shanshui san 蜃市山水叁In his landscapes, Yang Yongliang achieves strikingly visual effects by digitally manipulating photographic images. At first sight, the two prints appear like idyllic landscapes painted in ink, reminiscent of classic landscapes from the Song dynasty (960–1279). On closer inspection, Yang has substituted trees with telegraph poles and mountains with clusters of skyscrapers, pointing to the rapid transformation of cities and landscapes in present-day China.Yang Yongliang was born in 1980 in Jiading near Shanghai where he currently lives. He studied traditional calligraphy and painting before graduating in design from the Shanghai Fine Arts Institute.Yang Yongliang 楊泳梁 (born 1980)Shanghai 2007Digital picture, inkjet print on Epson textured fine art paperAsia 2008,3012.1

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END