Period:Unknown Production date:1763

Materials:paper

Technique:engraving, etching, letterpress,

Subjects:garden architecture chinese

Dimensions:Height: 536 millimetres (approx. page size) Width: 370 millimetres (approx. page size)

Description:

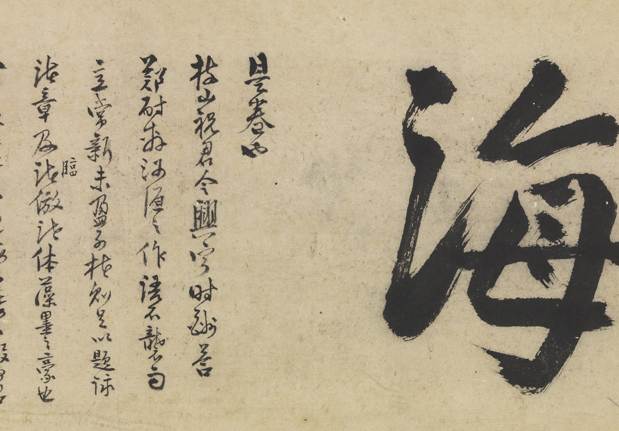

Book of architectural plans and designs for Kew Gardens, including the palace, the great pagoda, the mosque, the Gothic cathedral, the temples and the water engine, the designs mostly by the architect, and author of the volume,William Chambers. 1763 Engraved and etched plates, with letterpress title, dedication and three-page description

IMG

![图片[1]-print; book BM-1863-0509.239-273-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Rare books/mid_00134548_001.jpg)

Comments:(S. O’Connell, “London !753”, 2003, No.5.11) In 1731, shortly after his arrival in England, Frederick, Prince of Wales had leased a seventeenth-century house at Kew. He employed William Kent to enlarge and embellish it, but did not begin any extensive work on the grounds until 1750. By the time of his death on 20 March 1751, he had planted, according to George Vertue, “many curious and foreign trees”; he had erected the “House of Confucius” to the design of Joseph Goupy and was planning other garden buildings and sculpture. Princess Augusta continued the work under the guidance of Lord Bute, an ardent gardener and botanist. In 1758, she commissioned the “Alhambra” from William Chambers and by 1763 he had designed – as well as a number of hothouses or “stoves” – a mosque, a ruined arch, several Roman temples and the spectacular 163 feet high Great Pagoda which is still in situ.Horace Walpole claimed that Augusta spent between £30,000 and £40,000 on Kew. After her death the gardens were joined to the adjacent royal gardens of Richmond Lodge, already redesigned by Capability Brown. In succeeding decades, under the supervision of Sir Joseph Banks, they were to become the Royal Botanic Garden. With this fine volume Chambers was advertising his talents as an architect and making the buildings at Kew available to be copied. Publication was expensive and the young George III supported Chambers with a contribution of £800, no doubt persuaded of the value of promoting advanced British design and expertise. The volume follows a number of influential books of architectural engravings published in the earlier part of the century: Colen Campbell’s “Vitruvius Britannicus”, 1715-25, William Kent’s “Designs of Inigo Jones”, 1727, James Gibbs’s “Book of Architecture”, 1728, John Vardy’s “Some Designs of Mr Inigo Jones and Mr William Kent”, 1744. Chambers’s own “Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses”, 1757, recorded buildings he had seen in China in the 1740s.For the history of Kew Gardens, see R. Desmond, “Kew: The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens”, 1995; for Chambers, see J. Harris, “Sir William Chambers”, 1970.

Materials:paper

Technique:engraving, etching, letterpress,

Subjects:garden architecture chinese

Dimensions:Height: 536 millimetres (approx. page size) Width: 370 millimetres (approx. page size)

Description:

Book of architectural plans and designs for Kew Gardens, including the palace, the great pagoda, the mosque, the Gothic cathedral, the temples and the water engine, the designs mostly by the architect, and author of the volume,William Chambers. 1763 Engraved and etched plates, with letterpress title, dedication and three-page description

IMG

![图片[1]-print; book BM-1863-0509.239-273-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Rare books/mid_00134548_001.jpg)

Comments:(S. O’Connell, “London !753”, 2003, No.5.11) In 1731, shortly after his arrival in England, Frederick, Prince of Wales had leased a seventeenth-century house at Kew. He employed William Kent to enlarge and embellish it, but did not begin any extensive work on the grounds until 1750. By the time of his death on 20 March 1751, he had planted, according to George Vertue, “many curious and foreign trees”; he had erected the “House of Confucius” to the design of Joseph Goupy and was planning other garden buildings and sculpture. Princess Augusta continued the work under the guidance of Lord Bute, an ardent gardener and botanist. In 1758, she commissioned the “Alhambra” from William Chambers and by 1763 he had designed – as well as a number of hothouses or “stoves” – a mosque, a ruined arch, several Roman temples and the spectacular 163 feet high Great Pagoda which is still in situ.Horace Walpole claimed that Augusta spent between £30,000 and £40,000 on Kew. After her death the gardens were joined to the adjacent royal gardens of Richmond Lodge, already redesigned by Capability Brown. In succeeding decades, under the supervision of Sir Joseph Banks, they were to become the Royal Botanic Garden. With this fine volume Chambers was advertising his talents as an architect and making the buildings at Kew available to be copied. Publication was expensive and the young George III supported Chambers with a contribution of £800, no doubt persuaded of the value of promoting advanced British design and expertise. The volume follows a number of influential books of architectural engravings published in the earlier part of the century: Colen Campbell’s “Vitruvius Britannicus”, 1715-25, William Kent’s “Designs of Inigo Jones”, 1727, James Gibbs’s “Book of Architecture”, 1728, John Vardy’s “Some Designs of Mr Inigo Jones and Mr William Kent”, 1744. Chambers’s own “Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses”, 1757, recorded buildings he had seen in China in the 1740s.For the history of Kew Gardens, see R. Desmond, “Kew: The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens”, 1995; for Chambers, see J. Harris, “Sir William Chambers”, 1970.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END