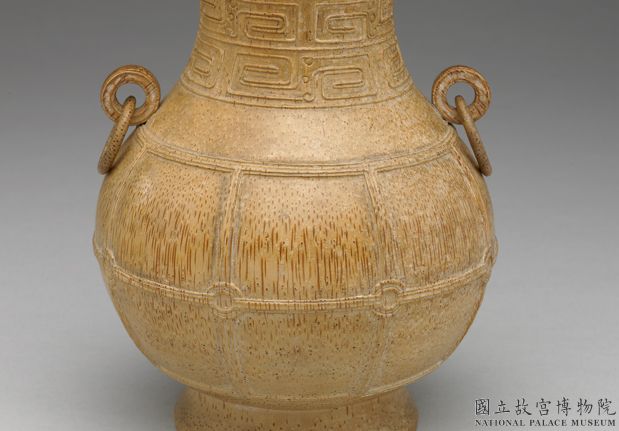

Period:Ming dynasty Production date:1450-1600 (circa)

Materials:earthenware

Technique:glazed, moulded,

Subjects:fish

Dimensions:Diameter: 11 centimetres Height: 2.80 centimetres

Description:

Turquoise-and-amber glazed earthenware funerary model of food (fish) in a dish.

IMG

![图片[1]-offering-dish BM-1927-1214.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/43/mid_00273557_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-offering-dish BM-1927-1214.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/43/mid_00499222_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:This set of model food dishes (BM 1927.1214.1-10) provided the tomb occupant with the ingredients for a lavish meal to enjoy beyond the grave. The earthenware set of ten comprises shallow dishes with rounded sides, everted rims and recessed unglazed bases which reach a pinnacle in the centre. They are covered inside and out with an uneven turquoise lead glaze. Inside each dish is a different raw food, modelled in relief, covered with a pale yellow or deep amber glaze.In Ming China, people generally ate a more varied diet than their Western contemporaries. Food was and to some extent still is both the great social cement and its lubricant. Food was not just for sustenance, but also for feasting, to celebrate religious, annual and family events, and social and business transactions. Pleasure in the consumption of food was not confined to the living but was also a prerequisite in the supernatural world. These model food dishes present the ingredients for a feast for the soul in the afterlife and give us an idea of the types of food enjoyed by the living in the Ming era. The major food groups – meat, poultry, fish, fruit, vegetables and cereals – are all represented and are arranged as five main meats and five accompanying dishes. A whole lamb, a pig, a rabbit, a fish and a goose are each modelled in relief on a different dish. Foods on the other five dishes – pomegranates, peaches, water chestnuts, shaobing [fried cakes] and ‘mantou’ [steamed bread] – are, intriguingly arranged in groups of four. This may be significant as the Chinese word 四 ‘si’ meaning four has the same pronunciation as but different tone from the word 死 ‘si’ meaning death. In addition to their reputation as typical dishes for a feast, these foods may also have had a symbolic significance. For example, peaches represented a wish for long life and pomegranates the desire for many sons.The presence of both ‘mantou’ and ‘shaobing’ suggests that this set was made in north China where noodles and steamed dough were eaten extensively. In south China the main filler for cooking was locally grown rice. Although the elite in northern China commonly ate rice in the Ming era, southerners did not consume steamed bread buns. In addition, the glaze and pinkish-beige clay body of the dishes indicate that Shaanxi is a likely provenance. Related turquoise and amber glazes were used to colour architectural tiles in north China. Indeed such similarities suggest that kilns producing tiles also manufactured models for burial.Degrading and iridescence of the glazes on the present set, together with traces of soil, confirm that it was removed from a burial context prior to its gift to the Museum in 1927.A comparable set of model food dishes was discovered on a rectangular table, together with a model stone folding armchair, in a tomb at Tongliang xian, Sichuan, belonging to Chen Pingzhou, who died in the first year of Wanli (1573). Other sets of dishes may be found in public collections, although there appears to be no identical set. A group of eight in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, was recently acquired together with a table (FE 110-1996).

Materials:earthenware

Technique:glazed, moulded,

Subjects:fish

Dimensions:Diameter: 11 centimetres Height: 2.80 centimetres

Description:

Turquoise-and-amber glazed earthenware funerary model of food (fish) in a dish.

IMG

![图片[1]-offering-dish BM-1927-1214.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/43/mid_00273557_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-offering-dish BM-1927-1214.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/43/mid_00499222_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:This set of model food dishes (BM 1927.1214.1-10) provided the tomb occupant with the ingredients for a lavish meal to enjoy beyond the grave. The earthenware set of ten comprises shallow dishes with rounded sides, everted rims and recessed unglazed bases which reach a pinnacle in the centre. They are covered inside and out with an uneven turquoise lead glaze. Inside each dish is a different raw food, modelled in relief, covered with a pale yellow or deep amber glaze.In Ming China, people generally ate a more varied diet than their Western contemporaries. Food was and to some extent still is both the great social cement and its lubricant. Food was not just for sustenance, but also for feasting, to celebrate religious, annual and family events, and social and business transactions. Pleasure in the consumption of food was not confined to the living but was also a prerequisite in the supernatural world. These model food dishes present the ingredients for a feast for the soul in the afterlife and give us an idea of the types of food enjoyed by the living in the Ming era. The major food groups – meat, poultry, fish, fruit, vegetables and cereals – are all represented and are arranged as five main meats and five accompanying dishes. A whole lamb, a pig, a rabbit, a fish and a goose are each modelled in relief on a different dish. Foods on the other five dishes – pomegranates, peaches, water chestnuts, shaobing [fried cakes] and ‘mantou’ [steamed bread] – are, intriguingly arranged in groups of four. This may be significant as the Chinese word 四 ‘si’ meaning four has the same pronunciation as but different tone from the word 死 ‘si’ meaning death. In addition to their reputation as typical dishes for a feast, these foods may also have had a symbolic significance. For example, peaches represented a wish for long life and pomegranates the desire for many sons.The presence of both ‘mantou’ and ‘shaobing’ suggests that this set was made in north China where noodles and steamed dough were eaten extensively. In south China the main filler for cooking was locally grown rice. Although the elite in northern China commonly ate rice in the Ming era, southerners did not consume steamed bread buns. In addition, the glaze and pinkish-beige clay body of the dishes indicate that Shaanxi is a likely provenance. Related turquoise and amber glazes were used to colour architectural tiles in north China. Indeed such similarities suggest that kilns producing tiles also manufactured models for burial.Degrading and iridescence of the glazes on the present set, together with traces of soil, confirm that it was removed from a burial context prior to its gift to the Museum in 1927.A comparable set of model food dishes was discovered on a rectangular table, together with a model stone folding armchair, in a tomb at Tongliang xian, Sichuan, belonging to Chen Pingzhou, who died in the first year of Wanli (1573). Other sets of dishes may be found in public collections, although there appears to be no identical set. A group of eight in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, was recently acquired together with a table (FE 110-1996).

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END