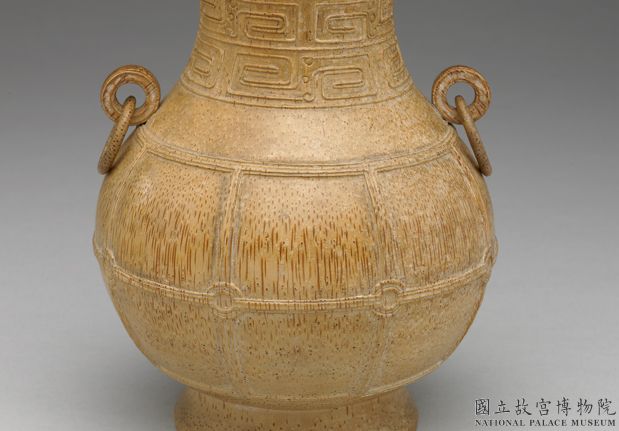

Period:Ming dynasty Production date:1522-1566

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed, underglazed,

Subjects:child fruit garden leisure/entertainment reading/writing

Dimensions:Diameter: 39 centimetres Height: 46 centimetres (with lid)

Description:

Large porcelain jar with cover decorated in underglaze blue. This magnificent covered jar is ovoid with a short neck, thickened at the rim, and a domed cover with a knob finial. The base is recessed and glazed with a broad foot ring. Typical of the Jiajing reign, it is painted in a deep dark blue, described as ink-blue or violet, beneath the glaze. Sixteen boys are shown playing in a garden. These children are occupied in a range of different games and activities: one rides a hobby horse while another holds a lotus-leaf parasol over his head, another selects an arrow from a quiver, a group of three sit at a table, one boy carries a vase containing a branch of coral, another carries a large fan on a long pole shading his companion, one rolls back his sleeves seemingly for a fight, another holds a fruit, another a stick of sugar cane, a baby crawls towards a book encouraged by a seated older child with a boy reading a book at a table, another pulls a cord attached to a toy cart. Below this is a border of overlapping lappets between double blue lines. Around the shoulder are four cartouches framing flowering and fruiting plants – possibly peaches, peonies, persimmons and daylilies. In between is a diaper border over which are painted symbols of wealth and luxury, such as a coin, branch of coral, an ingot and rhinoceros horns. The cover is decorated around the sides with alternating fruiting peach and ‘lingzhi’ sprays separated by ‘ruyi’ clouds. Eight lappets radiate from a spiral border around the base of the knob finial which is itself ornamented with a brocade ball design. Both jar and cover are glazed inside and the base is marked with a six-character Jiajing reign mark.

IMG

![图片[1]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00147664_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00147670_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00235771_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_RRC14799_base.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:In Confucian philosophy, many children, but particularly many sons, were essential for the fulfilment of family and ancestral duties, rites and ceremonies. The more sons one had, the better. In contrast to BM 1975.1028.23, whose inscription described the misery imposed on parents who have no children, this covered jar shows the joys of having many boys in the family. Images of babies, boys and girls on Ming dynasty porcelains are closely related to those found in contemporary Ming paintings and decorative arts, such as on lacquer wares, textiles and jades. Illustrations of ‘One Hundred Children’ represent a desire for fertility, wealth and happiness. Although the children appear to be playing freely, many of them are engaged in games with symbolic meaning, emblems for success in a future official life. Educating sons was a preoccupation of paramount importance. Through successful education young men could pass the imperial exams and gain high office and a good salary, bringing glory and advancement to their family. Several large imperial jars and covers of this type are known, including an example in the Tianminlou Collection. A covered Jiajing mark and period jar of this design in the Capital Museum, Beijing, was excavated in 1980 in Beijing at Chaoyang district. In total eight ceramics in the British Museum’s Ming collection portray the very young at play, all but one in underglaze blue.Childrens’ heads are shown shaved, with three small tufts of hair: on the forehead and either side of the cranium. Although this hairstyle was uncommon in the West where infants were shown in fine and applied arts with full heads of curly hair, it is still seen in mainland China today. Such a coiffure may have been adopted initially for practical reasons, such as prevention of the spread of lice, but enjoyed long-lived popularity. Children are rarely depicted wearing hats. However, when they are shown as budding bureaucrats they sport a black gauze hat with wings, typical of a mandarin of the day. Babies are often portrayed without bonnets, wearing little more than an enlarged bib which fastens around the neck and covers the torso in a diamond shape. Unlike children depicted in the European Renaissance, Chinese infants do not appear dressed entirely as miniature adults.Girls are rarely depicted on porcelain because of their inferior social position. Costumes for boys consisted of straight loose trousers over which layered long-sleeved knee-length robes were worn. These were secured by a belt at the waist leaving a V-necked opening. Jewellery for children in the Ming consisted of earrings and wrist bangles, but other accessories such as auspicious and protective charms would have been sewn on to costumes or worn around the neck. Shoes were made of textile, cotton and silk, with dark uppers and pale stippled soles.

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed, underglazed,

Subjects:child fruit garden leisure/entertainment reading/writing

Dimensions:Diameter: 39 centimetres Height: 46 centimetres (with lid)

Description:

Large porcelain jar with cover decorated in underglaze blue. This magnificent covered jar is ovoid with a short neck, thickened at the rim, and a domed cover with a knob finial. The base is recessed and glazed with a broad foot ring. Typical of the Jiajing reign, it is painted in a deep dark blue, described as ink-blue or violet, beneath the glaze. Sixteen boys are shown playing in a garden. These children are occupied in a range of different games and activities: one rides a hobby horse while another holds a lotus-leaf parasol over his head, another selects an arrow from a quiver, a group of three sit at a table, one boy carries a vase containing a branch of coral, another carries a large fan on a long pole shading his companion, one rolls back his sleeves seemingly for a fight, another holds a fruit, another a stick of sugar cane, a baby crawls towards a book encouraged by a seated older child with a boy reading a book at a table, another pulls a cord attached to a toy cart. Below this is a border of overlapping lappets between double blue lines. Around the shoulder are four cartouches framing flowering and fruiting plants – possibly peaches, peonies, persimmons and daylilies. In between is a diaper border over which are painted symbols of wealth and luxury, such as a coin, branch of coral, an ingot and rhinoceros horns. The cover is decorated around the sides with alternating fruiting peach and ‘lingzhi’ sprays separated by ‘ruyi’ clouds. Eight lappets radiate from a spiral border around the base of the knob finial which is itself ornamented with a brocade ball design. Both jar and cover are glazed inside and the base is marked with a six-character Jiajing reign mark.

IMG

![图片[1]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00147664_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00147670_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00235771_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-jar BM-1973-0417.1.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_RRC14799_base.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:In Confucian philosophy, many children, but particularly many sons, were essential for the fulfilment of family and ancestral duties, rites and ceremonies. The more sons one had, the better. In contrast to BM 1975.1028.23, whose inscription described the misery imposed on parents who have no children, this covered jar shows the joys of having many boys in the family. Images of babies, boys and girls on Ming dynasty porcelains are closely related to those found in contemporary Ming paintings and decorative arts, such as on lacquer wares, textiles and jades. Illustrations of ‘One Hundred Children’ represent a desire for fertility, wealth and happiness. Although the children appear to be playing freely, many of them are engaged in games with symbolic meaning, emblems for success in a future official life. Educating sons was a preoccupation of paramount importance. Through successful education young men could pass the imperial exams and gain high office and a good salary, bringing glory and advancement to their family. Several large imperial jars and covers of this type are known, including an example in the Tianminlou Collection. A covered Jiajing mark and period jar of this design in the Capital Museum, Beijing, was excavated in 1980 in Beijing at Chaoyang district. In total eight ceramics in the British Museum’s Ming collection portray the very young at play, all but one in underglaze blue.Childrens’ heads are shown shaved, with three small tufts of hair: on the forehead and either side of the cranium. Although this hairstyle was uncommon in the West where infants were shown in fine and applied arts with full heads of curly hair, it is still seen in mainland China today. Such a coiffure may have been adopted initially for practical reasons, such as prevention of the spread of lice, but enjoyed long-lived popularity. Children are rarely depicted wearing hats. However, when they are shown as budding bureaucrats they sport a black gauze hat with wings, typical of a mandarin of the day. Babies are often portrayed without bonnets, wearing little more than an enlarged bib which fastens around the neck and covers the torso in a diamond shape. Unlike children depicted in the European Renaissance, Chinese infants do not appear dressed entirely as miniature adults.Girls are rarely depicted on porcelain because of their inferior social position. Costumes for boys consisted of straight loose trousers over which layered long-sleeved knee-length robes were worn. These were secured by a belt at the waist leaving a V-necked opening. Jewellery for children in the Ming consisted of earrings and wrist bangles, but other accessories such as auspicious and protective charms would have been sewn on to costumes or worn around the neck. Shoes were made of textile, cotton and silk, with dark uppers and pale stippled soles.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END