Period:Unknown Production date:1590-1640 (if Chinese)

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed, underglazed,

Dimensions:Height: 26 centimetres

Description:

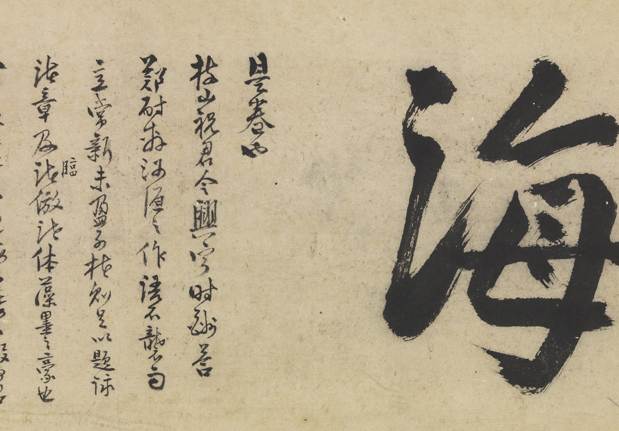

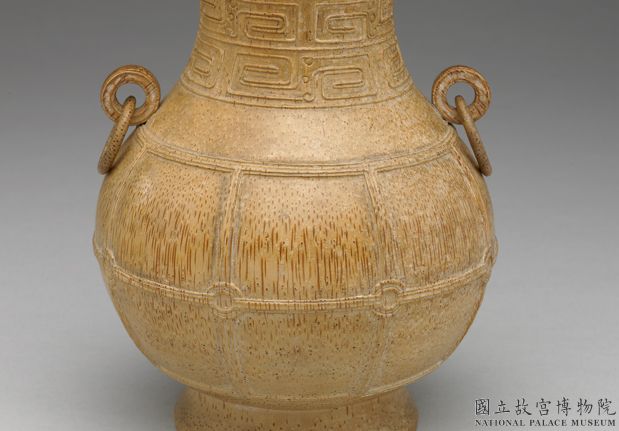

Three-sided porcelain flask with underglaze blue decoration. This unique flask is of triangular cross-section with rounded edges, a barrel-shaped neck which bulges in the middle and a three-sided spreading foot. Along each of the three vertical edges are at the shoulder a loop, towards the bottom of the flask a tubular attachment and in the foot a hole. It is painted under the glaze in blue cobalt with figures in double oval frames and with ornate medallions containing archaic-style characters. The flask’s iconography is unusual too. The balding old man with a stubbly chin, long whiskery eyebrows, open mouth and wrinkly skin, wearing a short pleated robe over trousers, is riding a leaf or reed across waves, surrounded by stormy cloud scrolls. There is a disc of light around his head and on either side are stellar constellations, five stars to the left and four to the right. The figure is Bodhidharma or Da Mo (fl. 470-516), traditionally believed to have founded the Chan Buddhist School, crossing the Yangzi on a reed. The stately female figure has a richly adorned Tang-style headdress and long flowing robes. Flanking her are two altar vases on raised stands with tubular attachments to their sides and ‘yin-yang’ symbols in their centres. Above her is the full moon emerging from a cloud. To the left, right and below her are trigrams comprised of three parallel whole and broken lines taken from the ‘Yijing’ [Book of Changes]. Surrounding her are the trigrams which represent thunder pronounced ‘chen’, wind ‘sun’ and fire ‘li’. The author suggests that she could be a local Jiangxi temple goddess. On the third side is an elderly male figure with a plump face, wearing a fur-trimmed hat and coat, bracelets and trousers. He has a satchel at his waist, a bundle of coral strapped to his back and is holding out a magic horn. On either side of the figure are stellar constellations composed of four stars each and below these are possibly quivers. Above the figure is a mystic emblem pronounced ‘wan’, given this sound as all good fortune and virtue are embodied in it, and two circles, while below is a trigram. The trigram ‘li’ represents fire, intelligence and brilliance and also appears on the side with the goddess. The base is partially glazed and cracked, revealing a yellowish body, and with grit adhesions.

IMG

![图片[1]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00267192_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355618_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355711_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355714_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355715_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355720_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355718_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355624_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355625_001.jpg)

![图片[10]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355626_001.jpg)

![图片[11]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355627_001.jpg)

![图片[12]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355628_001.jpg)

![图片[13]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355698_001.jpg)

![图片[14]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355701_001.jpg)

![图片[15]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355705_001.jpg)

![图片[16]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355707_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:The form of the bottle is unique and alien to Chinese ceramics and metal work. It is likely that the flask has a European prototype, possibly in leather. Using X-ray florescence, an area of blue drapery was examined and the results compared to data collected for an unpublished report by Mike Cowell. This showed the sample to be Chinese locally produced cobalt because of the presence of manganese, which is absent or minimal in imported cobalt from Persia, Iraq, Turkey and Syria, and because of the lack of arsenic and copper which are generally present in imported cobalt. Vessels with inscriptions describing their contents are not uncommon in China in the late Ming dynasty. However, the “Ben cao gang mu”, a dictionary of Chinese medicinal plants compiled by Li Shizhen in 1596, contains no reference to the present one. This is possibly because it is a lexicon of raw materials for drugs rather than the names of finished concoctions. Chinese medicine men and scholar-officials travelled a great deal and many believed in the powers of magical potions. The author suggests that this was a travelling container for a potion or medicine called ‘gui tian die’. Could the combination of the emblem ‘wan’ and the trigram ‘li’ be a pun, ‘wan li’ – ten thousand miles, referring to the distance this emissary has travelled to bring the exotic ingredients of magic coral and horn? This may be too far-fetched, but if the flask did contain an exotic potion, this identification of a stellar god bearing precious ingredients and another crossing the ocean does not seem improbable. It could be a pun on the ruling emperor’s name. Stellar gods belong to an enormous body of star lore which grew up alongside Chinese interest in astronomy and astrology. Henri Dore, in his “Recherches sur les Superstitions en Chine”, published a wide range of stellar gods, but these three neither individually nor as a group were among them. Chinese people selected gods who could secure fertility, wealth and health and prevent catastrophes, and picked and chose from among a vast pantheon of Daoist, Buddhist and popular dieties, many of whom must be unrecorded. Obviously the number three is very important in Daoism and the motifs which this flask bears may support an argument for its shape having a Daoist connection.Woodblock prints, made in Nanjing at the Fuchuntang between 1595 and 1610, show Bodhidharma in a similar pose. Coral, which was imported from Persia and Ceylon, was a symbol of longevity and official promotion as well as an ingredient in magic potions. The author suggests that the figure carrying a bundle of it may be a foreigner and can be compared to a Persian wearing a similar fur-trimmed hat with a floppy top depicted in an illustrated manuscript dated between 1539 and 1543 in the British Library, entitled ‘Khamseh of Nizami’, by Aqamirak.

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed, underglazed,

Dimensions:Height: 26 centimetres

Description:

Three-sided porcelain flask with underglaze blue decoration. This unique flask is of triangular cross-section with rounded edges, a barrel-shaped neck which bulges in the middle and a three-sided spreading foot. Along each of the three vertical edges are at the shoulder a loop, towards the bottom of the flask a tubular attachment and in the foot a hole. It is painted under the glaze in blue cobalt with figures in double oval frames and with ornate medallions containing archaic-style characters. The flask’s iconography is unusual too. The balding old man with a stubbly chin, long whiskery eyebrows, open mouth and wrinkly skin, wearing a short pleated robe over trousers, is riding a leaf or reed across waves, surrounded by stormy cloud scrolls. There is a disc of light around his head and on either side are stellar constellations, five stars to the left and four to the right. The figure is Bodhidharma or Da Mo (fl. 470-516), traditionally believed to have founded the Chan Buddhist School, crossing the Yangzi on a reed. The stately female figure has a richly adorned Tang-style headdress and long flowing robes. Flanking her are two altar vases on raised stands with tubular attachments to their sides and ‘yin-yang’ symbols in their centres. Above her is the full moon emerging from a cloud. To the left, right and below her are trigrams comprised of three parallel whole and broken lines taken from the ‘Yijing’ [Book of Changes]. Surrounding her are the trigrams which represent thunder pronounced ‘chen’, wind ‘sun’ and fire ‘li’. The author suggests that she could be a local Jiangxi temple goddess. On the third side is an elderly male figure with a plump face, wearing a fur-trimmed hat and coat, bracelets and trousers. He has a satchel at his waist, a bundle of coral strapped to his back and is holding out a magic horn. On either side of the figure are stellar constellations composed of four stars each and below these are possibly quivers. Above the figure is a mystic emblem pronounced ‘wan’, given this sound as all good fortune and virtue are embodied in it, and two circles, while below is a trigram. The trigram ‘li’ represents fire, intelligence and brilliance and also appears on the side with the goddess. The base is partially glazed and cracked, revealing a yellowish body, and with grit adhesions.

IMG

![图片[1]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00267192_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355618_001.jpg)

![图片[3]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355711_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355714_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355715_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355720_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355718_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355624_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355625_001.jpg)

![图片[10]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355626_001.jpg)

![图片[11]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355627_001.jpg)

![图片[12]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355628_001.jpg)

![图片[13]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355698_001.jpg)

![图片[14]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355701_001.jpg)

![图片[15]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355705_001.jpg)

![图片[16]-flask BM-1926-0426.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Ceramics/mid_00355707_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:The form of the bottle is unique and alien to Chinese ceramics and metal work. It is likely that the flask has a European prototype, possibly in leather. Using X-ray florescence, an area of blue drapery was examined and the results compared to data collected for an unpublished report by Mike Cowell. This showed the sample to be Chinese locally produced cobalt because of the presence of manganese, which is absent or minimal in imported cobalt from Persia, Iraq, Turkey and Syria, and because of the lack of arsenic and copper which are generally present in imported cobalt. Vessels with inscriptions describing their contents are not uncommon in China in the late Ming dynasty. However, the “Ben cao gang mu”, a dictionary of Chinese medicinal plants compiled by Li Shizhen in 1596, contains no reference to the present one. This is possibly because it is a lexicon of raw materials for drugs rather than the names of finished concoctions. Chinese medicine men and scholar-officials travelled a great deal and many believed in the powers of magical potions. The author suggests that this was a travelling container for a potion or medicine called ‘gui tian die’. Could the combination of the emblem ‘wan’ and the trigram ‘li’ be a pun, ‘wan li’ – ten thousand miles, referring to the distance this emissary has travelled to bring the exotic ingredients of magic coral and horn? This may be too far-fetched, but if the flask did contain an exotic potion, this identification of a stellar god bearing precious ingredients and another crossing the ocean does not seem improbable. It could be a pun on the ruling emperor’s name. Stellar gods belong to an enormous body of star lore which grew up alongside Chinese interest in astronomy and astrology. Henri Dore, in his “Recherches sur les Superstitions en Chine”, published a wide range of stellar gods, but these three neither individually nor as a group were among them. Chinese people selected gods who could secure fertility, wealth and health and prevent catastrophes, and picked and chose from among a vast pantheon of Daoist, Buddhist and popular dieties, many of whom must be unrecorded. Obviously the number three is very important in Daoism and the motifs which this flask bears may support an argument for its shape having a Daoist connection.Woodblock prints, made in Nanjing at the Fuchuntang between 1595 and 1610, show Bodhidharma in a similar pose. Coral, which was imported from Persia and Ceylon, was a symbol of longevity and official promotion as well as an ingredient in magic potions. The author suggests that the figure carrying a bundle of it may be a foreigner and can be compared to a Persian wearing a similar fur-trimmed hat with a floppy top depicted in an illustrated manuscript dated between 1539 and 1543 in the British Library, entitled ‘Khamseh of Nizami’, by Aqamirak.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END