Period:Unknown Production date:1793-1796

Materials:paper

Technique:drawn

Subjects:emperor/empress chinese costume

Dimensions:Height: 443 millimetres (album cover) Height: 238 millimetres (sheet) Width: 180 millimetres Width: 334 millimetres

Description:

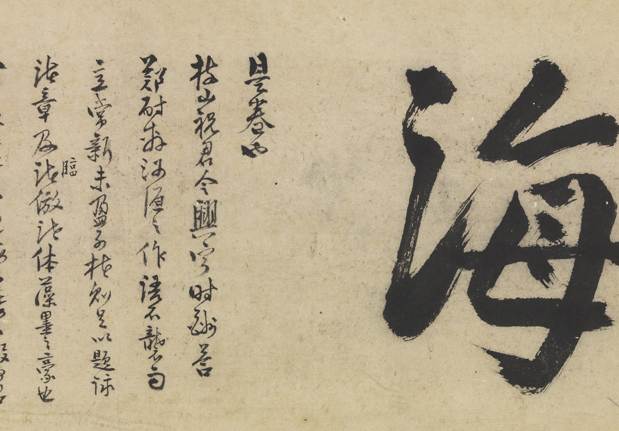

Portrait of Qianlong, Emperor of China, seated on a golden throne on a balcony with a view in the distance to the left; from an album of 82 drawings of China. 1796 Watercolour, ink and graphite

IMG

![图片[1]-drawing; album; print study BM-1865-0520.193-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01428413_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-drawing; album; print study BM-1865-0520.193-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_PDB25861.jpg)

Comments:In September 1792, the young artist William Alexander (1767-1817) set sail as part of the ninety-four- strong First British Embassy to China, headed by Earl (then Viscount) George Macartney (1737 – 1806). The primary aim of the Embassy was the amelioration of conditions for trade between Britain and China, and although its main protagonist failed in this respect, one major achievement of the two-year endeavour was its recording and later dissemination (in the form of both travel accounts and visual records) of an unprecedented amount of information about China and the Chinese – its inhabitants, edifices, customs and technology, amongst many other things. As articulated by Stacey Sloboda, this strand of the Embassy’s mandate was part of “a larger trend of European Empiricism in the 19th century that contributed to the emerging British imperial project of knowledge as a form of control.” (Sloboda, 2008, p. 30). William Alexander made a significant contribution to this effort; there are around 1000 sketches and drawings dating from his two years in China, and indeed he appears to have supported himself for almost a decade upon his return to Britain through exhibiting and publishing Chinese subjects. His sole-authored volumes include the following: “Views of the headlands, islands, etc., taken during a voyage to, and along the eastern coast of China, in the years 1792 & 1793” (1798); “Chinese Life”, a collection of etchings (1798-1805); “The Costume of China” (published in 1805 as a single volume at six guineas by W. Miller) which boasted 48 coloured plates (the plates are dated 1797-1804, and according to Legouix were originally produced in sets of four); and “Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese” (1814; at 3 guineas) with 50 plates. In the text accompanying the latter two publications Alexander often uses the terms ‘Chinese’ and ‘Tartar’ interchangeably, and he is very critical of Chinese culture and society.This vibrant and detailed watercolour depicts the Emperor of China, who descended from the powerful Manchu Ch’ing dynasty. Qianlong reigned from 1736-96. Lord Macartney and selected members of the Embassy travelled to the summer retreat of the Emperor in September 1793 for an audience with him; the failure of this is evidenced by Macartney’s dismissal only a month later and the remarkable letter written by the Emperor to George III rebuffing the latter’s hopes for an improved trade treaty.Alexander, who was junior draftsman on the Embassy, was not taken along to Chengde for Macartney’s audience with the Emperor, and Susan Legouix has suggested that he probably only saw the Emperor once in the flesh and then only briefly (Legouix, 1980, p. 63). Alexander’s likenesses of the Emperor were criticised by Sir George Staunton, Principal Secretary to the Embassy who authored an official account of the endeavour, but it is important to note that Alexander was working one step removed from his subject. His knowledge of the Emperor’s appearance was facilitated both by drawings made by colleagues who were in attendance at the audience and oral descriptions. Similarly, his watercolours of the Great Wall were also made second-hand.This portrait of the Emperor is one of four known versions – all watercolours – of the same composition. Two others can be found, respectively, in a volume of Alexander’s Chinese sketches at the India Office Library Collection and in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. The fourth (Legouix, 1980, cat. no. 45) was in a private collection in 1980. This portrait of Qianlong was engraved by Collyer as the frontispiece of the official published record of the Embassy, George Staunton’s ‘An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China’ (2 vols., 1797). Alexander later included the portrait, with some variations, as the second plate in ‘Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese’ (published 1814; etched lettering below the image “Pub. Jan 1814, by J. Murray, Albemarle Street.”).This watercolour is found within an album of watercolours by Alexander all of which depict subjects from the 1792-1794 Embassy to China. There is a list of descriptions of the watercolours inserted in the front of the album, and this drawing is listed as: “N.o 1. Portrait of Tchien-Lung, Emperor of China, in the eighty fourth year of his Age, & fifty seventh of his reign.”The album is finely bound in citron morocco with a banded spine ornately tooled in compartments; the second compartment is lettered “DRAWINGS TAKEN IN CHINA”. The album is in its own slip-case. It contains two leaves with a list of contents and eighty-two leaves (443 x 334mm, 1865,0520.193-274) with drawings of Chinese subjects laid down within drawn borders, including several studies for aquatints in ‘Costume of China’ and one for an engraving in Staunton’s ‘An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China’; there are also 7 blank leaves and purple moiré silk endpapers. The subjects include: portraits of (using eighteenth-century transliterations of the Chinese) the Emperor Tchien-Lung, Van-ta-Zhin, Chow-ta-Zhin and the Fou-yen of Canton; views of Tong-Tchou-Fow, a grotto at Macao, a tower near Tien-sin, ruins of a bridge at San-Win-Wey, the Lui-Fung-Ta temple, a pagoda at Lin-Tsin, the river of Ning-Po, objects at Tong-Tchiou-Fou and Yuen-Min-Yuen; tombs and monuments (including that of the Hon. Charles Cathcart at Angeru Point in Java), a water-wheel, weapons, boats, a fishing-bird; an idol at a Tong-Tchow and a representation of the god Lui-shin; people of various trades and social ranks such as mandarins, soldiers, fishermen, servants, peasants, labourers, boatmen, a priest, an actor, a tradesman, and also women and children. 1793-6.The registration numbers have been allocated to the individual drawings rather than the album leaves. There are additional manuscript numbers 1-82 on the album leaves with drawings (within the drawn borders), and one drawing is also numbered “62” (1865,0520.227).See the individual catalogue entries for a description of the individual watercolours (1865,0520.193-274.).A few drawings are signed “W.A.” (194, 195, 198) and some are also dated; “W.Alexander, 96” (193) or “W.A., 96” (196-7). Each album leaf is inscribed, below the drawing, with the picture’s subject and several are also dated in 1793-4. These dates relate to those of the events depicted in the images; it appears that the watercolours themselves were executed in 1796, presumably worked up by Alexander back in England from sketches made on the spot in China.The album was purchased by the British Museum in 1865 from the Rev. Charles Burney (1815-1907), son of the Archdeacon of St. Albans, Charles Parr Burney (1785-1864) and grandson of the classical scholar and collector Charles Burney (1757-1817). Moreover, according to his sister Fanny Burney’s recollection, their father, the musicologist Dr. Charles Burney (1726-1814) was consulted by Macartney prior to the Embassy as to which musical instruments and compositions to take to impress the Chinese. Many of the leaves are stamped with the following watermark: “1794 J Whatman”. A white ticket lettered in italics on the inside front cover of the album identifies the binder as Heinrich Walther, who was active in London in the decades around 1800 (see Howard Millar Nixon and Kenneth H. Oldaker, “British Bookbindings: Presented by Kenneth H. Oldaker to the Chapter Library of Westminster Abbey” (1982) pp. 67-8). There are references in the descriptive list of drawings bound in at the front of the volume to ‘The Costume of China’ but none to “Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese”, suggesting that the album was compiled at some point between 1805 and 1814. Legouix identifies the handwriting of the titles on the mounts of the drawings as Alexander’s, and in turn this handwriting seems to correlate with the descriptive list of subjects at the front of the album (Legouix, 1980, p. 30). It therefore seems very likely that Alexander compiled the album himself, though his purpose in doing so is unknown. An item in the Sotheby’s sale catalogue of Alexander’s pictures, prints and drawings (February 1817) could potentially be identified with the BM album. This is contained with the description of lot 868, which is headed “Original and unpublished Chinese Drawings, by Mr. Alexander, viz.”; the fourth item reads “One hundred Ditto, ditto [the previous two items are listed as sketches of the “people, manners, customs, and other curious objects of the Country” and of “Shipping, Boats, Natural History &c”, respectively], many of them highly finished, in a quarto port-folio, in morocco.” Although much of the sale catalogue is annotated, no buyer or price is given for this lot; if this were the occasion that the album entered the Burney collection, then either Charles Burney the scholar and book collector (who died in December 1817) or his son Charles Parr Burney may have been the purchaser.(Carly Collier, June 2013)Literature:Richard Garnett, ‘Alexander, William (1767–1816)’, rev. Heather M. MacLennan, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.Susan Legouix, ‘Image of China: William Alexander’, 1980.Patrick Connor and Susan Legouix, ‘William Alexander: An English Artist in Imperial China’, Exh. Cat., Brighton, 1981.Peter Marshall, `Britain and China in the Late Eighteenth Century’ in Robert Bickers, Ritual & diplomacy : the Macartney mission to China 1792-1794: papers presented at the 1992 conference of the British Association for Chinese Studies marking the bicentenary of the Macartney mission to China, (London : British Association for Chinese Studies , 1993) pp. 11-29.Frances Wood, `Britain’s First View of China: The Macartney Embassy 1792-1794’, RSA Journal, (1994).___________, `Closely Observed China: From William Alexander’s Sketches to his Published Work’, British Library Journal, 24 (1998) pp. 98-121. Stacey Sloboda, ‘Picturing China: William Alexander and the visual language of Chinoiserie’, British Art Journal, 9, no. 2 (2008), pp. 28-36.

Materials:paper

Technique:drawn

Subjects:emperor/empress chinese costume

Dimensions:Height: 443 millimetres (album cover) Height: 238 millimetres (sheet) Width: 180 millimetres Width: 334 millimetres

Description:

Portrait of Qianlong, Emperor of China, seated on a golden throne on a balcony with a view in the distance to the left; from an album of 82 drawings of China. 1796 Watercolour, ink and graphite

IMG

![图片[1]-drawing; album; print study BM-1865-0520.193-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_01428413_001.jpg)

![图片[2]-drawing; album; print study BM-1865-0520.193-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/43/mid_PDB25861.jpg)

Comments:In September 1792, the young artist William Alexander (1767-1817) set sail as part of the ninety-four- strong First British Embassy to China, headed by Earl (then Viscount) George Macartney (1737 – 1806). The primary aim of the Embassy was the amelioration of conditions for trade between Britain and China, and although its main protagonist failed in this respect, one major achievement of the two-year endeavour was its recording and later dissemination (in the form of both travel accounts and visual records) of an unprecedented amount of information about China and the Chinese – its inhabitants, edifices, customs and technology, amongst many other things. As articulated by Stacey Sloboda, this strand of the Embassy’s mandate was part of “a larger trend of European Empiricism in the 19th century that contributed to the emerging British imperial project of knowledge as a form of control.” (Sloboda, 2008, p. 30). William Alexander made a significant contribution to this effort; there are around 1000 sketches and drawings dating from his two years in China, and indeed he appears to have supported himself for almost a decade upon his return to Britain through exhibiting and publishing Chinese subjects. His sole-authored volumes include the following: “Views of the headlands, islands, etc., taken during a voyage to, and along the eastern coast of China, in the years 1792 & 1793” (1798); “Chinese Life”, a collection of etchings (1798-1805); “The Costume of China” (published in 1805 as a single volume at six guineas by W. Miller) which boasted 48 coloured plates (the plates are dated 1797-1804, and according to Legouix were originally produced in sets of four); and “Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese” (1814; at 3 guineas) with 50 plates. In the text accompanying the latter two publications Alexander often uses the terms ‘Chinese’ and ‘Tartar’ interchangeably, and he is very critical of Chinese culture and society.This vibrant and detailed watercolour depicts the Emperor of China, who descended from the powerful Manchu Ch’ing dynasty. Qianlong reigned from 1736-96. Lord Macartney and selected members of the Embassy travelled to the summer retreat of the Emperor in September 1793 for an audience with him; the failure of this is evidenced by Macartney’s dismissal only a month later and the remarkable letter written by the Emperor to George III rebuffing the latter’s hopes for an improved trade treaty.Alexander, who was junior draftsman on the Embassy, was not taken along to Chengde for Macartney’s audience with the Emperor, and Susan Legouix has suggested that he probably only saw the Emperor once in the flesh and then only briefly (Legouix, 1980, p. 63). Alexander’s likenesses of the Emperor were criticised by Sir George Staunton, Principal Secretary to the Embassy who authored an official account of the endeavour, but it is important to note that Alexander was working one step removed from his subject. His knowledge of the Emperor’s appearance was facilitated both by drawings made by colleagues who were in attendance at the audience and oral descriptions. Similarly, his watercolours of the Great Wall were also made second-hand.This portrait of the Emperor is one of four known versions – all watercolours – of the same composition. Two others can be found, respectively, in a volume of Alexander’s Chinese sketches at the India Office Library Collection and in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. The fourth (Legouix, 1980, cat. no. 45) was in a private collection in 1980. This portrait of Qianlong was engraved by Collyer as the frontispiece of the official published record of the Embassy, George Staunton’s ‘An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China’ (2 vols., 1797). Alexander later included the portrait, with some variations, as the second plate in ‘Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese’ (published 1814; etched lettering below the image “Pub. Jan 1814, by J. Murray, Albemarle Street.”).This watercolour is found within an album of watercolours by Alexander all of which depict subjects from the 1792-1794 Embassy to China. There is a list of descriptions of the watercolours inserted in the front of the album, and this drawing is listed as: “N.o 1. Portrait of Tchien-Lung, Emperor of China, in the eighty fourth year of his Age, & fifty seventh of his reign.”The album is finely bound in citron morocco with a banded spine ornately tooled in compartments; the second compartment is lettered “DRAWINGS TAKEN IN CHINA”. The album is in its own slip-case. It contains two leaves with a list of contents and eighty-two leaves (443 x 334mm, 1865,0520.193-274) with drawings of Chinese subjects laid down within drawn borders, including several studies for aquatints in ‘Costume of China’ and one for an engraving in Staunton’s ‘An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China’; there are also 7 blank leaves and purple moiré silk endpapers. The subjects include: portraits of (using eighteenth-century transliterations of the Chinese) the Emperor Tchien-Lung, Van-ta-Zhin, Chow-ta-Zhin and the Fou-yen of Canton; views of Tong-Tchou-Fow, a grotto at Macao, a tower near Tien-sin, ruins of a bridge at San-Win-Wey, the Lui-Fung-Ta temple, a pagoda at Lin-Tsin, the river of Ning-Po, objects at Tong-Tchiou-Fou and Yuen-Min-Yuen; tombs and monuments (including that of the Hon. Charles Cathcart at Angeru Point in Java), a water-wheel, weapons, boats, a fishing-bird; an idol at a Tong-Tchow and a representation of the god Lui-shin; people of various trades and social ranks such as mandarins, soldiers, fishermen, servants, peasants, labourers, boatmen, a priest, an actor, a tradesman, and also women and children. 1793-6.The registration numbers have been allocated to the individual drawings rather than the album leaves. There are additional manuscript numbers 1-82 on the album leaves with drawings (within the drawn borders), and one drawing is also numbered “62” (1865,0520.227).See the individual catalogue entries for a description of the individual watercolours (1865,0520.193-274.).A few drawings are signed “W.A.” (194, 195, 198) and some are also dated; “W.Alexander, 96” (193) or “W.A., 96” (196-7). Each album leaf is inscribed, below the drawing, with the picture’s subject and several are also dated in 1793-4. These dates relate to those of the events depicted in the images; it appears that the watercolours themselves were executed in 1796, presumably worked up by Alexander back in England from sketches made on the spot in China.The album was purchased by the British Museum in 1865 from the Rev. Charles Burney (1815-1907), son of the Archdeacon of St. Albans, Charles Parr Burney (1785-1864) and grandson of the classical scholar and collector Charles Burney (1757-1817). Moreover, according to his sister Fanny Burney’s recollection, their father, the musicologist Dr. Charles Burney (1726-1814) was consulted by Macartney prior to the Embassy as to which musical instruments and compositions to take to impress the Chinese. Many of the leaves are stamped with the following watermark: “1794 J Whatman”. A white ticket lettered in italics on the inside front cover of the album identifies the binder as Heinrich Walther, who was active in London in the decades around 1800 (see Howard Millar Nixon and Kenneth H. Oldaker, “British Bookbindings: Presented by Kenneth H. Oldaker to the Chapter Library of Westminster Abbey” (1982) pp. 67-8). There are references in the descriptive list of drawings bound in at the front of the volume to ‘The Costume of China’ but none to “Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese”, suggesting that the album was compiled at some point between 1805 and 1814. Legouix identifies the handwriting of the titles on the mounts of the drawings as Alexander’s, and in turn this handwriting seems to correlate with the descriptive list of subjects at the front of the album (Legouix, 1980, p. 30). It therefore seems very likely that Alexander compiled the album himself, though his purpose in doing so is unknown. An item in the Sotheby’s sale catalogue of Alexander’s pictures, prints and drawings (February 1817) could potentially be identified with the BM album. This is contained with the description of lot 868, which is headed “Original and unpublished Chinese Drawings, by Mr. Alexander, viz.”; the fourth item reads “One hundred Ditto, ditto [the previous two items are listed as sketches of the “people, manners, customs, and other curious objects of the Country” and of “Shipping, Boats, Natural History &c”, respectively], many of them highly finished, in a quarto port-folio, in morocco.” Although much of the sale catalogue is annotated, no buyer or price is given for this lot; if this were the occasion that the album entered the Burney collection, then either Charles Burney the scholar and book collector (who died in December 1817) or his son Charles Parr Burney may have been the purchaser.(Carly Collier, June 2013)Literature:Richard Garnett, ‘Alexander, William (1767–1816)’, rev. Heather M. MacLennan, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.Susan Legouix, ‘Image of China: William Alexander’, 1980.Patrick Connor and Susan Legouix, ‘William Alexander: An English Artist in Imperial China’, Exh. Cat., Brighton, 1981.Peter Marshall, `Britain and China in the Late Eighteenth Century’ in Robert Bickers, Ritual & diplomacy : the Macartney mission to China 1792-1794: papers presented at the 1992 conference of the British Association for Chinese Studies marking the bicentenary of the Macartney mission to China, (London : British Association for Chinese Studies , 1993) pp. 11-29.Frances Wood, `Britain’s First View of China: The Macartney Embassy 1792-1794’, RSA Journal, (1994).___________, `Closely Observed China: From William Alexander’s Sketches to his Published Work’, British Library Journal, 24 (1998) pp. 98-121. Stacey Sloboda, ‘Picturing China: William Alexander and the visual language of Chinoiserie’, British Art Journal, 9, no. 2 (2008), pp. 28-36.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END