Period:Unknown Production date:5thC-6thC

Materials:gold

Technique:

Dimensions:Diameter: 16.50 millimetres Weight: 0.59 grammes

Description:

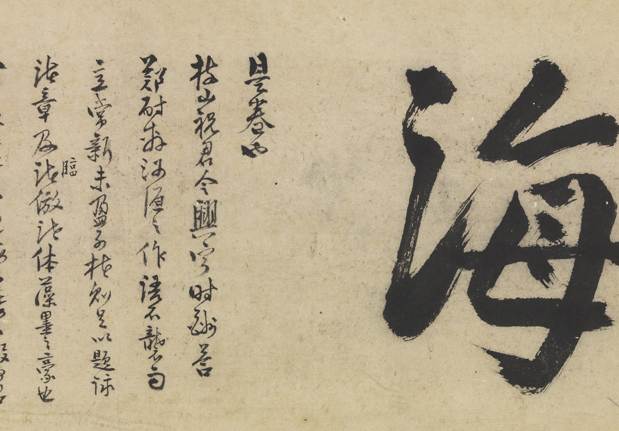

Gold coin; imitation of Byzantine coin.

IMG

![图片[1]-coin; imitation BM-IA-XII.b.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Miscellaneous objects/mid_Misc_4666.jpg)

Comments:Stein 1928, p.648: “Tomb i.5, which lay nearest to i.1 in a southerly direction, was found to contain three bodies, lying with their heads to the south. The one next to the entrance, (a), was big, obviously of a man, while the one in the middle, (b), was small and probably that of a woman. … From the mouth of (a) a thin gold coin (Pl.CXX) was recovered, derived like the one in Ast.i.3 from a type of Justinian I, but struck only on one side and manifestly a more distant imitation.”Stein 1928, p.646: “The fact that out of the four coins actually found by us in the mouths of Astana corpses three are Byzantine gold pieces or imitations of such pieces (Ast.i.3.023; Ast.i.5.08; Ast.i.6.03) and one a Sasanian silver coin (Ast.v.2.02) might naturally predispose us to connect this practice with the ancient Greek custom of placing a coin between the lips of the dead as the fare to Charon, the ferryman of Hades. But the reference with which M. Chavannes kindly supplied me in 1916 to a Buddhist story in the Chinese Tripitaka suggests that the custom was not unknown in the Far East also. [fn4: See Chavannes, Cinq cents contes et apologues extraits du Tripitaka chinois, i, p.248] It must further be borne in mind that as China had never had a gold or silver coinage, those who at Turfan wished to provide their dead with an adequate obolus for the journey to the world beyond would necessarily have to use a coin of Western origin for their pious purpose, if they wished it to be of precious metal.”

Materials:gold

Technique:

Dimensions:Diameter: 16.50 millimetres Weight: 0.59 grammes

Description:

Gold coin; imitation of Byzantine coin.

IMG

![图片[1]-coin; imitation BM-IA-XII.b.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Unknown/Miscellaneous objects/mid_Misc_4666.jpg)

Comments:Stein 1928, p.648: “Tomb i.5, which lay nearest to i.1 in a southerly direction, was found to contain three bodies, lying with their heads to the south. The one next to the entrance, (a), was big, obviously of a man, while the one in the middle, (b), was small and probably that of a woman. … From the mouth of (a) a thin gold coin (Pl.CXX) was recovered, derived like the one in Ast.i.3 from a type of Justinian I, but struck only on one side and manifestly a more distant imitation.”Stein 1928, p.646: “The fact that out of the four coins actually found by us in the mouths of Astana corpses three are Byzantine gold pieces or imitations of such pieces (Ast.i.3.023; Ast.i.5.08; Ast.i.6.03) and one a Sasanian silver coin (Ast.v.2.02) might naturally predispose us to connect this practice with the ancient Greek custom of placing a coin between the lips of the dead as the fare to Charon, the ferryman of Hades. But the reference with which M. Chavannes kindly supplied me in 1916 to a Buddhist story in the Chinese Tripitaka suggests that the custom was not unknown in the Far East also. [fn4: See Chavannes, Cinq cents contes et apologues extraits du Tripitaka chinois, i, p.248] It must further be borne in mind that as China had never had a gold or silver coinage, those who at Turfan wished to provide their dead with an adequate obolus for the journey to the world beyond would necessarily have to use a coin of Western origin for their pious purpose, if they wished it to be of precious metal.”

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END