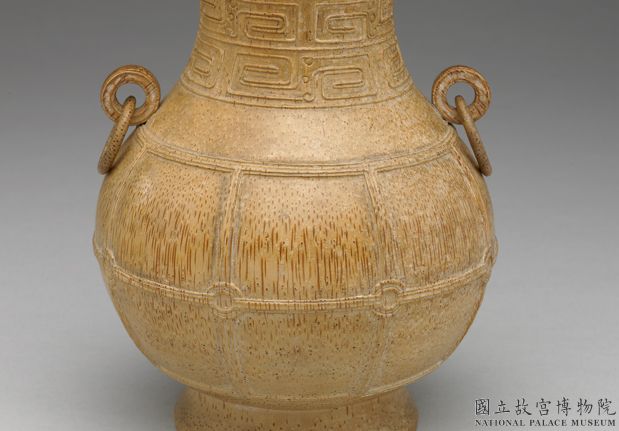

Period:Ming dynasty Production date:1522-1566 (circa)

Materials:porcelain, gold,

Technique:glazed, painted, underglazed,

Subjects:reading/writing

Dimensions:Height: 7.70 centimetres (with cover) Length: 13.50 centimetres Width: 13.50 centimetres

Description:

Square porcelain seal box and cover with overglaze red, green, yellow, turquoise and black enamels and traces of gilding. This square seal box has a deep tray with a thick foot, recessed base, stepped mouth and shallower flat-topped slightly domed cover. The cover is painted with figures in an interior scene with lavish furnishings of taste, rank and scholarship – branch coral in a vase, books on the tables, and canopies and fans. A magistrate, dispensing justice, is attired in the garb of officialdom, with a black winged hat, round-necked red robe, square rank badge with a bird and an elaborate girdle. He is sitting behind a desk on a horseshoe-backed chair, draped with a tiger pelt. The desk is covered with textiles and laid out with two brushes on a mountain-shaped brush rest, an ink slab and a blank scroll. Behind him is a screen showing a carp rising up out of the sea towards the sun. Carp fight their way upstream, thus it is a metaphor for success against the odds and more specifically for success in the civil service exams. In front of the magistrate, two men point their fingers at one another. One, wearing a jez-style hat, patched round-necked robe and trousers, is being escorted out of the room by a servant in a yellow robe with contrasting green and red sleeves, tied at the waist with a large sash, long boots and hat with upturned peak. Rejoicing at this enforced exit is another figure wearing a round black hat with a brim and finial, a green robe with a gold rank badge and black boots. Between them on the floor is an abandoned open book and writing brush. An inscription in red enamel inside the cover reads 投 笔 封 印 ‘Tou bi feng yin’ [Throw away the pen, close up the official seals]. Inside the tray a ‘qilin’ is surrounded by stellar constellations and by ‘ruyi’ fungus at each corner. The edges of the cover are painted with a lotus scroll reserved in white with yellow centres on a red ground and the base with a band of peonies reserved in white on a green ground and with daisies below in white on a red ground very similar to those on BM 1945.1016.16. The base is marked with an underglaze blue mark which reads 篆 匣 便 用 ‘Zhuan xia bian yong’ [Seal container for use as required].

IMG

![图片[1]-box(seal box); cover BM-1936-1012.193.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00268920_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:China, the largest bureaucratically organized country in the world, employed seals in all aspects of official life. They were made most commonly from jade and other stones, metal and porcelain, but also from bamboo, ivory and other natural materials. Seals were pressed into coloured ink paste, generally red, though other colours were used too, and then applied to official and other documents including personal letters and invitations. Seals were also used as a mark of ownership on precious books, calligraphy and painting. In China they take the place of a signature and no official business can be conducted without the relevant stamp of office or personal seal. The earliest seals were stamped into moist clay, but from the Han dynasty they were applied to paper and to silk. The present box was used on an official’s desk to store one or more seals with either relief or intaglio characters. Clever magistrates appear in a number of popular stories of the Ming period. Indeed, in many stories a clever magistrate is the main protagonist. He was a surrogate for the emperor and therefore represented the highest civil authority in the district. It was one of his primary duties to administer law and order. In a criminal case the magistrate had to bring the offender to book, conduct the trial and pronounce the sentence. He could rely on underlings, secretaries and constables to make local enquiries, procure witness statements and arrest suspects, but could also leave his court incognito to pursue his own investigations, rather like the Duke in Shakespeare’s ‘Measure for Measure’. In the late sixteenth century, there were approximately 20,000 members of the civil service of whom 2,000 held office in the capital, Beijing. The upper ranks wore red robes and the lower echelons blue robes.

Materials:porcelain, gold,

Technique:glazed, painted, underglazed,

Subjects:reading/writing

Dimensions:Height: 7.70 centimetres (with cover) Length: 13.50 centimetres Width: 13.50 centimetres

Description:

Square porcelain seal box and cover with overglaze red, green, yellow, turquoise and black enamels and traces of gilding. This square seal box has a deep tray with a thick foot, recessed base, stepped mouth and shallower flat-topped slightly domed cover. The cover is painted with figures in an interior scene with lavish furnishings of taste, rank and scholarship – branch coral in a vase, books on the tables, and canopies and fans. A magistrate, dispensing justice, is attired in the garb of officialdom, with a black winged hat, round-necked red robe, square rank badge with a bird and an elaborate girdle. He is sitting behind a desk on a horseshoe-backed chair, draped with a tiger pelt. The desk is covered with textiles and laid out with two brushes on a mountain-shaped brush rest, an ink slab and a blank scroll. Behind him is a screen showing a carp rising up out of the sea towards the sun. Carp fight their way upstream, thus it is a metaphor for success against the odds and more specifically for success in the civil service exams. In front of the magistrate, two men point their fingers at one another. One, wearing a jez-style hat, patched round-necked robe and trousers, is being escorted out of the room by a servant in a yellow robe with contrasting green and red sleeves, tied at the waist with a large sash, long boots and hat with upturned peak. Rejoicing at this enforced exit is another figure wearing a round black hat with a brim and finial, a green robe with a gold rank badge and black boots. Between them on the floor is an abandoned open book and writing brush. An inscription in red enamel inside the cover reads 投 笔 封 印 ‘Tou bi feng yin’ [Throw away the pen, close up the official seals]. Inside the tray a ‘qilin’ is surrounded by stellar constellations and by ‘ruyi’ fungus at each corner. The edges of the cover are painted with a lotus scroll reserved in white with yellow centres on a red ground and the base with a band of peonies reserved in white on a green ground and with daisies below in white on a red ground very similar to those on BM 1945.1016.16. The base is marked with an underglaze blue mark which reads 篆 匣 便 用 ‘Zhuan xia bian yong’ [Seal container for use as required].

IMG

![图片[1]-box(seal box); cover BM-1936-1012.193.a-b-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Ming dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00268920_001.jpg)

Comments:Harrison-Hall 2001:China, the largest bureaucratically organized country in the world, employed seals in all aspects of official life. They were made most commonly from jade and other stones, metal and porcelain, but also from bamboo, ivory and other natural materials. Seals were pressed into coloured ink paste, generally red, though other colours were used too, and then applied to official and other documents including personal letters and invitations. Seals were also used as a mark of ownership on precious books, calligraphy and painting. In China they take the place of a signature and no official business can be conducted without the relevant stamp of office or personal seal. The earliest seals were stamped into moist clay, but from the Han dynasty they were applied to paper and to silk. The present box was used on an official’s desk to store one or more seals with either relief or intaglio characters. Clever magistrates appear in a number of popular stories of the Ming period. Indeed, in many stories a clever magistrate is the main protagonist. He was a surrogate for the emperor and therefore represented the highest civil authority in the district. It was one of his primary duties to administer law and order. In a criminal case the magistrate had to bring the offender to book, conduct the trial and pronounce the sentence. He could rely on underlings, secretaries and constables to make local enquiries, procure witness statements and arrest suspects, but could also leave his court incognito to pursue his own investigations, rather like the Duke in Shakespeare’s ‘Measure for Measure’. In the late sixteenth century, there were approximately 20,000 members of the civil service of whom 2,000 held office in the capital, Beijing. The upper ranks wore red robes and the lower echelons blue robes.

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END