Period:Northern Song dynasty Production date:1086-1125

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed

Dimensions:Diameter: 6.50 centimetres (foot) Diameter: 4.40 centimetres (mouth) Diameter: 11 centimetres (widest point) Height: 20.10 centimetres Weight: 0.40 kilograms

Description:

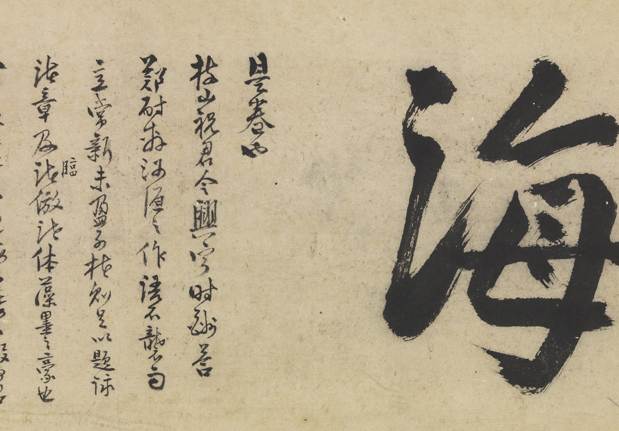

Bottle Ru ware, made of blue-green, crackled, glazed stoneware.

IMG

![图片[1]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_RRC15516.jpg)

![图片[2]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01075912_003.jpg)

![图片[3]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00182202_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00208896_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00222942_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00223219_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00309215_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00418605_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01076122_001.jpg)

![图片[10]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01182621_001.jpg)

Comments:Rawson 1992:Bottle-shaped vases of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1126) were probably developed from Tang dynasty Buddhist bronze and white-ware flasks (see, for example, BM 1909.0401.76). The shape continued throughout the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties, when porcelain versions from South China were decorated with either incised or painted ornament. The proportions of Northern Song monochrome vases vary from kiln to kiln, this example being most closely matched in Yaozhou wares from Shaanxi province. The shape shows high-quality glazes to advantage; the thick, smooth, duck-egg blue glaze on this piece covers the entire vessel except for the footring. Harrison-Hall 2015Ru ware wine bottleStoneware with blue-grey-green crackled glazeChina, Henan province, Baofeng county, QingliangsiNorthern Song dynasty, 1086-1125Height: 20 cmBritish Museum, given by R.A. Holt (1978,0522.1)Potters working at Qingliangsi, the main Ru ware production site in Baofeng county, Henan province, made beautiful celadon glazed stonewares for twenty or perhaps forty years between 1086 and 1106 or 1125. Archaeologists have excavated a bottle similar to this one at Qingliangsi. From their first production, the status of Ru ware was clearly superior to most other ceramics and ranked above all other celadons. Ye Zhi (active 1250-1300) refers to official orders of Ru ware for the court from Ruzhou. In 1151 the Gaozong emperor (1127-1162) visited his loyal official Zhang Jun, who gave the emperor treasured gifts, including sixteen Northern Ru wares. Among these forms listed by Zhou Mi in Wulin jiushi is a Ru wine bottle. The colour of the bottle’s glaze conjures up the appearance of ancient jades which were greatly admired in China. Song dynasty authors describe the Ru glaze as containing powdered agate, which was mined locally near the Qingliangsi kiln. The fine bluish colour of this glaze is in fact due to dissolved iron oxide, together with very low levels of titanium dioxide. Ru ware potters seem to have practised wood firing in small-chambered, oval-shaped kilns, even though most northern Chinese kilns at this time were fired with coal. Ru wares have a slightly underfired (1200-1250 degrees Centigrade), thin, pale grey stoneware body, with a comparatively thick celadon glaze. Potters closely monitored their firing temperatures, as evidenced by the huozhao [firing temperature detectors] excavated at the Qingliangsi kiln site. Artisans also covered the saggars in which the ceramics were fired with a layer of fire-resistant slip, which helped keep the temperature even inside (see Sun 2008, pp. 153-164). Korean celadons and Chinese Ru wares have chemically similar glazes, suggesting an early international exchange of technology (see Wood 1999, pp. 125-129) (JHH)

Materials:porcelain

Technique:glazed

Dimensions:Diameter: 6.50 centimetres (foot) Diameter: 4.40 centimetres (mouth) Diameter: 11 centimetres (widest point) Height: 20.10 centimetres Weight: 0.40 kilograms

Description:

Bottle Ru ware, made of blue-green, crackled, glazed stoneware.

IMG

![图片[1]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_RRC15516.jpg)

![图片[2]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01075912_003.jpg)

![图片[3]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00182202_001.jpg)

![图片[4]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00208896_001.jpg)

![图片[5]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00222942_001.jpg)

![图片[6]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00223219_001.jpg)

![图片[7]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00309215_001.jpg)

![图片[8]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_00418605_001.jpg)

![图片[9]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01076122_001.jpg)

![图片[10]-bottle BM-1978-0522.1-China Archive](https://chinaarchive.net/Northern Song dynasty/Ceramics/mid_01182621_001.jpg)

Comments:Rawson 1992:Bottle-shaped vases of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1126) were probably developed from Tang dynasty Buddhist bronze and white-ware flasks (see, for example, BM 1909.0401.76). The shape continued throughout the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties, when porcelain versions from South China were decorated with either incised or painted ornament. The proportions of Northern Song monochrome vases vary from kiln to kiln, this example being most closely matched in Yaozhou wares from Shaanxi province. The shape shows high-quality glazes to advantage; the thick, smooth, duck-egg blue glaze on this piece covers the entire vessel except for the footring. Harrison-Hall 2015Ru ware wine bottleStoneware with blue-grey-green crackled glazeChina, Henan province, Baofeng county, QingliangsiNorthern Song dynasty, 1086-1125Height: 20 cmBritish Museum, given by R.A. Holt (1978,0522.1)Potters working at Qingliangsi, the main Ru ware production site in Baofeng county, Henan province, made beautiful celadon glazed stonewares for twenty or perhaps forty years between 1086 and 1106 or 1125. Archaeologists have excavated a bottle similar to this one at Qingliangsi. From their first production, the status of Ru ware was clearly superior to most other ceramics and ranked above all other celadons. Ye Zhi (active 1250-1300) refers to official orders of Ru ware for the court from Ruzhou. In 1151 the Gaozong emperor (1127-1162) visited his loyal official Zhang Jun, who gave the emperor treasured gifts, including sixteen Northern Ru wares. Among these forms listed by Zhou Mi in Wulin jiushi is a Ru wine bottle. The colour of the bottle’s glaze conjures up the appearance of ancient jades which were greatly admired in China. Song dynasty authors describe the Ru glaze as containing powdered agate, which was mined locally near the Qingliangsi kiln. The fine bluish colour of this glaze is in fact due to dissolved iron oxide, together with very low levels of titanium dioxide. Ru ware potters seem to have practised wood firing in small-chambered, oval-shaped kilns, even though most northern Chinese kilns at this time were fired with coal. Ru wares have a slightly underfired (1200-1250 degrees Centigrade), thin, pale grey stoneware body, with a comparatively thick celadon glaze. Potters closely monitored their firing temperatures, as evidenced by the huozhao [firing temperature detectors] excavated at the Qingliangsi kiln site. Artisans also covered the saggars in which the ceramics were fired with a layer of fire-resistant slip, which helped keep the temperature even inside (see Sun 2008, pp. 153-164). Korean celadons and Chinese Ru wares have chemically similar glazes, suggesting an early international exchange of technology (see Wood 1999, pp. 125-129) (JHH)

© Copyright

The copyright of the article belongs to the author, please keep the original link for reprinting.

THE END